Prostatitis is inflammation of the prostate gland. It is the most common urological problem in men under 50 years old, with an overall prevalence of 2.2-9.7%.

Prostatitis is comprised of acute bacterial prostatitis, chronic bacterial prostatitis, nonbacterial prostatitis, and prostatodynia*.

In this article, we shall predominantly focus on acute bacterial prostatitis, discussing its clinical features, investigations, and management.

*The National Institute of Health classification involves Categories I, II, IIIA, IIIB and IV, all of which near identically correlate to the above classification.

Pathophysiology

Most cases of acute bacterial prostatitis are caused by ascending urethral infection, although occasionally direct or lymphatic spread from the rectum or hematogenous spread via bacterial sepsis can be the cause.

Causative organisms include E. Coli (most common), Enterobacter, Serratia, Pseudomonas, and Proteus species. Sexually transmitted infections, such as Chlamydia or Gonorrhoea, are a rare cause.

Chronic bacterial prostatitis is chronic bacterial infection of the prostate with or without prostatitis symptoms and is thought to be the sequelae of inadequately treated acute prostatitis.

Risk Factors

For acute bacterial prostatitis:

- Indwelling catheters

- Phimosis or urethral stricture

- Recent surgery, including cystoscopy or transrectal prostate biopsy

- Immunocompromised

In addition, for chronic prostatitis:

- Intraprostatic ductal reflux

- Neuroendocrine dysfunction

- Dysfunctional bladder

Clinical Features

Acute bacterial prostatitis can present with lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS), features of systemic infection (including pyrexia), perineal or suprapubic pain, or urethral discharge.

On rectal examination, there is often a very tender and boggy prostate. Associated inguinal lymphadenopathy may also be present.

Chronic prostatitis should be suspected in men who complain of pelvic pain or discomfort for at least 3 months (Prostatodynia), alongside LUTS; the perineum is the most common site for pain, however pain can occur in the suprapubic region, lower back, or rectum.

Investigations

Urine culture are the first line investigations* in the acute setting for suspected cases. Antibiotic therapy can be guided from any sensitivities obtained.

*Previously, the prostate massage was utilised to obtain suitable samples for culture in cases of suspected prostatitis however this is no longer recommended as part of routine practice

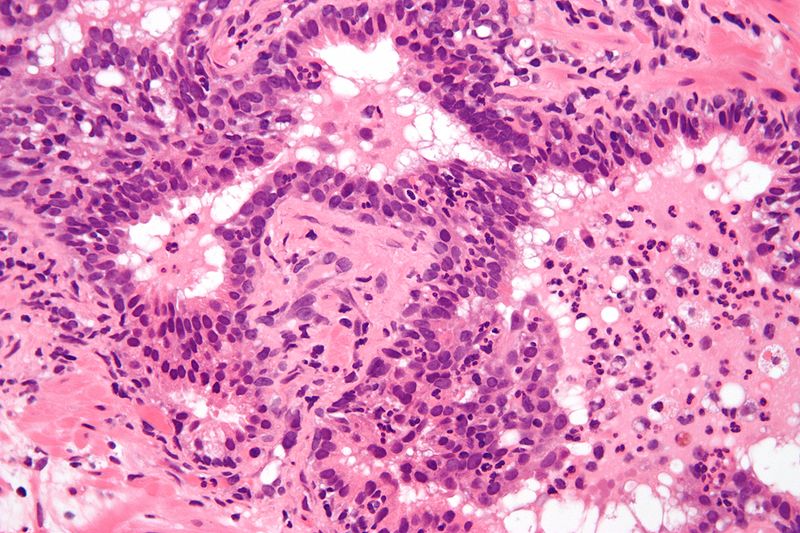

Figure 2 – Histology demonstrating acute inflammation of prostate tissue

Other investigations* to consider include an STI screen and routine bloods, including FBC, CRP, and U&Es (prostate specific antigen (PSA) will often be elevated in cases, therefore is not routinely performed).

Further investigations are only preformed in the secondary care setting and are usually indicated when initial therapy has failed or to investigate for potential underlying causes.

In patients who failed to respond to antibiotic therapy, other pathologies such as prostate abscess need to be ruled out using transrectal prostatic ultrasound (TRUS) or CT imaging.

*Meares and Stamey’s 4 cups urinary sediment were previously used, but due to poor practicality and time consumption, they are now rarely used in current practice.

Management

The mainstay of the management of acute bacterial prostatitis is via prolonged antibiotic treatment, typically a quinolone due to their good penetration into the prostate. Ensure suitable analgesia (typically paracetamol and NSAIDs) is also provided.

Alpha blockers or 5a-redictase inhibitors can be used as second line therapy, especially for chronic prostatitis cases.

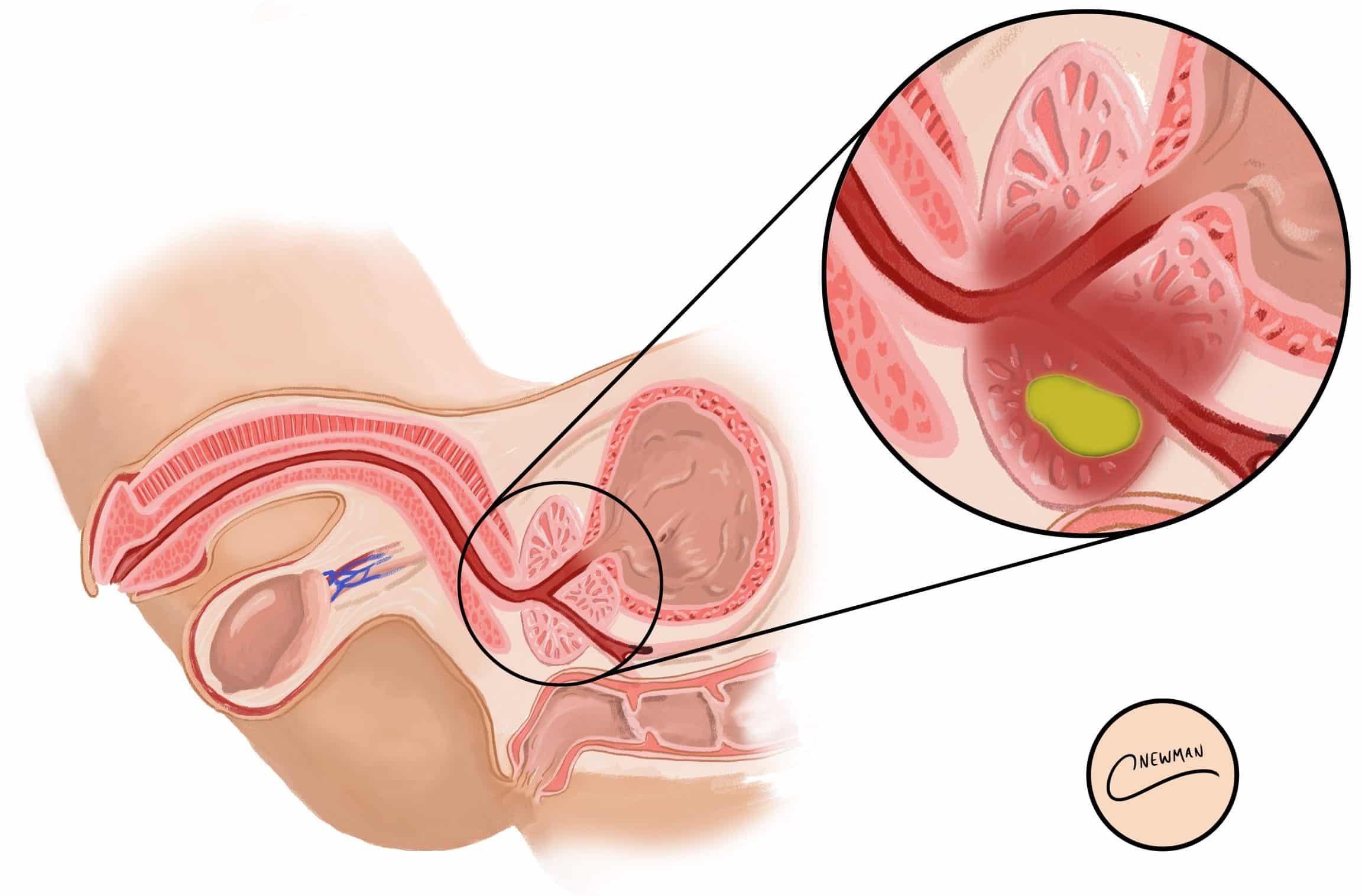

For patients that are considered to be severely ill or are unable to tolerate oral antibiotics, then admission to hospital may be necessary. Specialist input may be required those patients with diabetes mellitus, long-term catheter, immunocompromised, or suspected prostatic abscess (Fig. 3).

Those with pre-existing urological condition (e.g. BPH) may warrant referral to urology following the treatment of the acute infection for further management.

Figure 3 – Illustration of patient with prostatitis and a developing abscess

Further Management

When managing chronic prostatitis, it should be explained to the patient that the cause is not always understood and therefore can be difficult to treat. Management is primarily focused on symptom control (oral analgesia with stool softeners if any painful defecation).

Significant LUTS can be managed well with a 4-6-week trial of an alpha blocker (e.g. doxazosin, terazosin, tamsulosin). A 6-week course of antibiotics may also be warranted if symptoms have been present for less than 6 months.

If symptoms persist after urological treatment and management, consider referral to a chronic pain specialist. For CPPS, psychological therapies are an additional therapeutic option. An MDT approach (urologists, pain specialists, specialist physiotherapists, GPs, cognitive behavioural therapists, sexual health specialists) is recommended for optimal outcome.

Key Points

- Prostatitis is inflammation of the prostate gland

- Patients with acute bacterial prostatitis can present with LUTS, pyrexia, perineal or suprapubic pain, or urethral discharge

- Diagnosis is though clinical features and microbiology, although imaging can aid too

- Mainstay of treatment is through prolonged antibiotic treatment and analgesia