Introduction

Osteoarthritis (OA) is the most common arthropathy and is a leading cause of pain and disability in the Western world. As an example, symptomatic knee OA occurs in 15% of adults >55 years old, with a radiographic incidence of >80% in those over 75 years old.

It is a condition characterised by the progressive loss of articular cartilage and remodelling of the underlying bone. In this article, we shall look at the pathophysiology, clinical features and management of osteoarthritis.

Pathophysiology

Osteoarthritis is traditionally thought of as a ‘wear and tear’ disease which occurs as we age. However, recent research suggests otherwise.

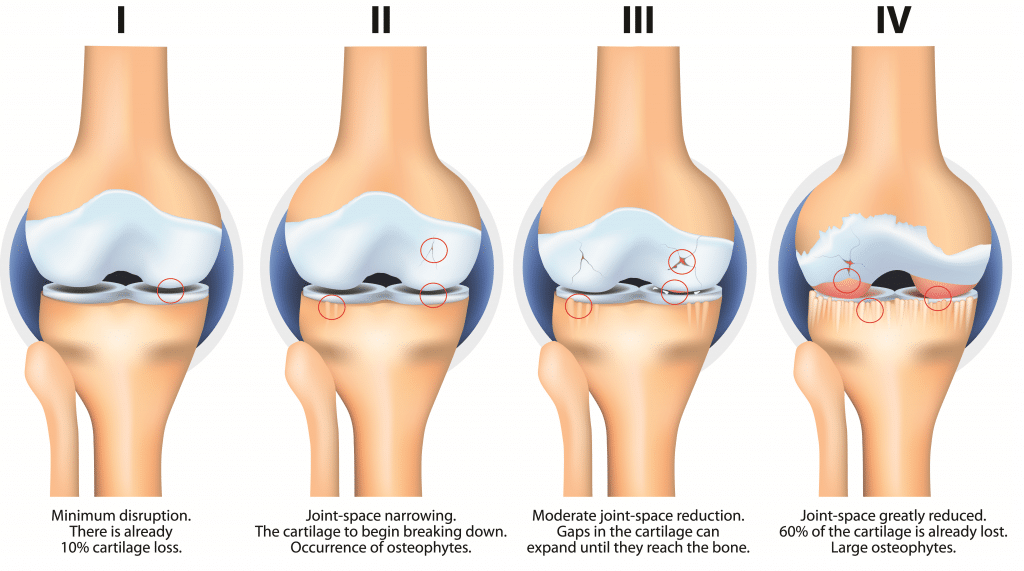

The pathogenesis of OA involves a degradation of cartilage and remodelling of bone due to an active response of chondrocytes in the articular cartilage and the inflammatory cells in the surrounding tissues.

The release of enzymes from these cells break down collagen and proteoglycans, destroying the articular cartilage. The exposure of the underlying subchondral bone results in sclerosis, followed by reactive remodelling changes that lead to the formation of osteophytes and subchondral bone cysts. The joint space is progressively lost over time.

Risk Factors

Osteoarthritis has a multifactorial aetiology and can be primary (with no obvious cause) or secondary (due to trauma, infiltrative disease or connective tissue diseases).

Risk factors for primary OA include obesity, advancing age, female gender, and manual labour occupations.

Clinical Features

The most common joints affected by osteoarthritis are the small joints of the hands and feet, the hip joint, and the knee joint.

Patients typically present with symptoms that are insidious, chronic, and gradually worsening. Clinical features include pain and stiffness in joints, worsened with activity* and relieved by rest. Pain tends to worsen throughout the day, whereas stiffness tends to improve. Prolonged OA results in deformity and a reduced range of movement.

On examination, inspect for deformity; there are some common characteristic findings depending on the joint affected, such as Bouchard nodes (swelling of PIPJs) or Heberden nodes (swelling of DIPJs) in the hands, and fixed flexion deformity or varus malalignment in the knees.

Feel for crepitus throughout the range of movement. Movement of the joint is generally reduced and painful.

*Joint stiffness and pain that improves with activity is characteristically seen in inflammatory arthropathies (e.g. rheumatoid arthritis).

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnoses for osteoarthritis will depend on which area of the body is affected. However, some universal conditions include inflammatory arthropathies (e.g. rheumatoid arthritis), crystal arthropathies (e.g. gout or CPPD), septic arthritis, fractures, bursitis, or malignancy (primary or metastatic).

Joint specific differential diagnoses for osteoarthritis:

- Hand – De Quervain’s tenosynovitis, rheumatoid arthritis, and gout

- Hip – trochanteric bursitis, radiculopathy, spinal stenosis, or iliotibial band syndrome

- Knee – meniscal or ligament tears, or chondromalacia patellae

Investigations

Osteoarthritis is primarily a clinical diagnosis. Investigations can be used to exclude differential diagnosis; routine blood tests can be useful to exclude inflammatory or infective causes and radiographs are useful for confirming the diagnosis (Fig. 3) and excluding fractures.

Radiological Appearances

The classical radiological features of osteoarthritis are:

- Loss of joint space

- Osteophytes

- Subchondral cysts

- Subchondral sclerosis

Figure 3 – Radiographic evidence of osteoarthritis affecting (A) hip (B) elbow (C) ankle

Management

The management of osteoarthritis involves options ranging from conservative to medical to surgical.

Conservative

Patients should be educated about their condition and its progression, including advise on joint protection and emphasising the importance of strengthening and exercise. Patients who are overweight should also be advised on weight loss.

Some non-pharmacological interventions that can be offered include local heat or ice packs, joint supports, and physiotherapy (most effective option for longer-term outcomes).

Medical

Simple analgesics and topical NSAIDs are the mainstay of most medical management for OA, alongside the conservative measures.

There is varying success with the use of intra-articular steroid injections*. These are commonly administered in the outpatient clinic in cases where the presence of pain remains despite oral analgesics.

*Steroid injections are typically mixed with local anaesthetic; whilst this improves the patients symptoms for a few hours, there is often a subsequent ‘steroid flare’, during which the patient’s symptoms worsen for a few days.

Surgical

If conservative and medical interventions fail, then surgical intervention may be considered, especially if their joint symptoms have a substantial impact on their quality of life.

The mainstay of management is with arthroplasty, however other options include osteotomy and arthrodesis (joint fusion)

Key Points

- Osteoarthritis is a condition characterised by the progressive loss of articular cartilage and remodelling of the underlying bone

- Risk factors include obesity, advancing age, female gender, and manual labour occupations

- Patients present with pain and stiffness in joints, worsened with activity and relieved by rest, with associated clinical signs depending on the joint involved

- It is a clinical diagnosis that can be managed conservatively initially, however may require surgical intervention if significant impact to quality of life remains