Cryptorchidism is a congenital absence of one or both testes in the scrotum due to a failure of the testes to descend during development.

Epidemiology

Cryptorchidism, or the failure of testicular descent into the scrotum, is a surgical condition found in 6% of newborns, but drops to 1.5-3.5% of males at 3 months. Cryptorchidism can broadly be defined in 3 groups:

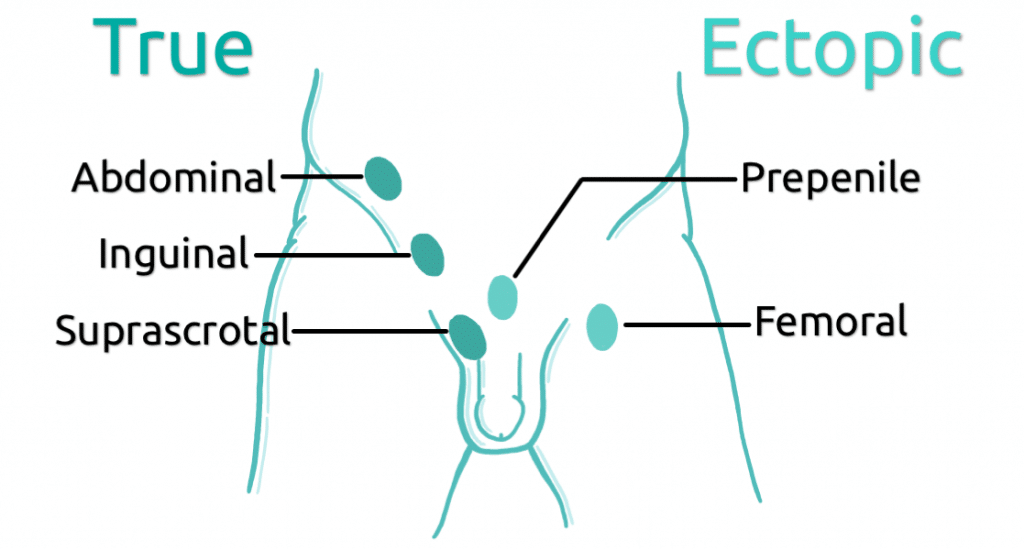

- True undescended testis: where testis is absent from the scrotum but lies along the line of testicular descent

- Ectopic testis: where the testis is found away from the normal path of decent

- Ascending testis: where a testis previously identified in the scrotum undergoes a secondary ascent out of the scrotum.

Pathophysiology

Under normal embryological development the testis descends from the abdomen to the scrotum, pulled by the gubernaculum, within the processes vaginalis. This process is incomplete in the context of true undescended testis; or tracks to an abnormal position in an ectopic testis. However, particularly with bilateral cryptorchidism, hormonal causes such as androgen insensitivity syndrome or disorder of sex development must also be excluded.

Risk Factors

Risk factors include:

- prematurity,

- low birth weight,

- having other abnormalities of genitalia (i.e. hypospadias)

- having a first degree relative with cryptorchidism.

Clinical Features

From history

One of the key elements in the history is to clarify if the testis has ever been seen or palpated within the scrotum, such as in the newborn check. Sometimes parents may note the testicle in the scrotum in certain situation, such as in a warm bath.

From examination

Initial inspection may reveal testis within the scrotum, therefore a diagnosis of retractile or normal descended testis can be made. If not, one should proceed to palpation to locate the testis. Around 80% of undescended testis are palpable, therefore should be found with a good examination.

To start, have the infant/child laid flat on the bed, aim to keep the child as comfortable and relaxed as possible. With warm hands, palpate laterally with your left hand, from the inguinal ring and work along the inguinal canal to the pubic symphysis, from there your other hand can be used to palpated the testis in the scrotum. If found, one should attempt to see if the testis can be gently milked down to the base of the scrotum, in which case a diagnosis of retractile testis can be made, if it is pulled down but under tension in the base, this commonly referred to as a ‘high scrotal’ or simply ‘high testis’.

Sometimes the testis may be found within the groin, along the inguinal canal, but cannot bring it further, therefore an ‘inguinal undescended testis’ has been found.

Around 20% of undescended testis are impalpable and are therefore: ectopic, intra-abdominal, absent, or impalpably small.

One suggestion for when you are having difficulties finding the testis during examination, is to add a little soap to finger tips to remove any friction to see if the testis can be found along the inguinal canal; the testis should roll easily under the finger tips and will not feel dissimilar to a raised enlarged lymph node, although obviously in a different, deeper anatomical location.

Differential Diagnosis

The key differentials (see figure 1 for location) are distinguishing between:

- Normal retractile testis – the testis is seen intermittently in the scrotum and with minimal traction can be pulled to the base of the scrotum

- A true undescended testis (palpable or impalpable) – testicle located along the normal decent pathway, but cannot be manipulated to the base of the scrotum

- Ectopic testis – testis is present, but is not found along the normal pathway of decent.

- Absent testis or “vanishing testis”

- Bilaterally impalpable testes in the context of underlying DSD or endocrine

Management

Initial management

If DSD suspected, undescended testis associated with ambiguous genitalia or hypospadias, or bilateral undescended testis are found: urgent referral to senior paediatrician within 24 hours, ideally with access to paediatric endocrinology and urology services. This may be a presentation of congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH) and are therefore at risk of salt-losing crisis, requiring high dose sodium chloride therapy and careful glucose monitoring followed by steroid replacement.

Role of imaging – No imaging modality has been shown to be of benefit in the diagnosis of undescended testis. Both USS and MRI have been showed to have low sensitivity and be poor at locating the testis and therefore plays no role in the pre-operative management of these patients.

Definitive and Long-term management

At birth – review at 6-8 weeks of age

At 6-8 weeks – if fully descended, no further action. If unilateral, re-examine at 3 months

At 3 months – If testis is retractile, advise annual follow up (due to risk of ascending testis). If undescended, refer to paediatric surgery/urology for definitive intervention – ideally occurring 6 – 12 months of age.

Intervention:

The intervention is dependent on clinical findings and the suspected position of the undescended testis. If unable to find the testis on examination, it is important to identify if the testis is absent or intra-abdominal. Therefore, an examination under anaesthesia followed by laparoscopy remains the mainstay of intervention in order to locate an impalpable testis (see flow diagram below)

- If the testis is palpable, an open orchidopexy can be performed. Via a groin incision, the process vaginalis and cremasteric covering is separated from the cord and testis mobilised and fixed in the scrotum.

- If the testis is intra-abdominal a single or 2-stage procedure (Fowler-Stephens) can be adopted. If a 2-stage procedure is adopted, initially testicular vessels are located and ligated, allowing for more robust collateral vessels to allow a second stage to bring the testis into the scrotum at a second operation 6 months later. This can be sometimes done in a single procedure of the cord length is deemed adequate without dividing the testicular vessels.

- Alternative findings at laparoscopy may be an atrophic testis, which should be removed, or an absent testis with blind-ending vas and testicular vessels, or the vas and vessels entering the deep inguinal ring, in which case groin exploration should be performed.

Complications

Surgical complications:

Short term complications include infection, bleeding and wound dehiscence. Long term there is a small risk of testicular atrophy and testicular re-ascent.

Complications of an undescended testis:

- Impaired fertility – as testis are 2-3⁰ C warmer if intra-abdominal, this can effect spermatogenesis. Although fertility in unilateral undescended testis is around 90%, this has been reported to drop to around 53% if bilateral. Risk of infertility increases with delayed correction.

- Testicular cancer – 2-3 times more common with a history of undescended testis (2-3%), and this risk double if correction is undertaken after puberty. In addition to the managing the risk of testicular cancer, orchidopexy also allows for self-examination for testicular abnormalities by the patient when they are older.

- Torsion – undescended testis are at higher risk of torsion.

References:

| [1] | https://cks.nice.org.uk/undescended-testes |

| [2] | Thomas, D.F., Duffy, P.G. and Rickwood, A.M. eds., 2008. Essentials of paediatric urology (pp. 73-91). London: Informa Healthcare. |