Introduction

Crohn’s disease (CD) is one of the main types of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), along with Ulcerative Colitis (UC).

The prevalence of the condition is about 150 per 100,000 people in the UK (slightly less common than UC) and has a bimodal peak age of presentation of between 15-30 years and 60-80 years.

The disease typically follows a remitting and relapsing course. Severe exacerbations may be life-threatening, causing severe systemic upset, bowel perforation, or even mortality.

Pathophysiology

Crohn’s disease can affect any part of the gastrointestinal tract, from mouth to anus, although common targets are the distal ileum and proximal colon. However, much of the aetiology of Crohn’s disease remains unknown.

It is characterised by transmural inflammation (affecting all layers of the bowel) in the affected region of bowel, producing deep ulcers and fissures (a “cobblestone appearance”). The inflammation is not continuous, forming skip lesions throughout the bowel (Table 1).

The microscopic appearance of Crohn’s disease is non-caseating granulomatous inflammation.

Due to the transmural nature of the inflammation, fistula can form from affected bowel to adjacent structures, resulting in perianal fistula (occurring in 54% of CD patients), entero-enteric fistula (24%), recto-vaginal (9%), entero-cutaneous fistula, or entero-vesicalar fistula.

Much like UC, it appears to have a familial link, however unlike UC, smoking will often worsen symptoms.

| Ulcerative Colitis | Crohn’s Disease | |

| Site Involvement | Large bowel | Entire gastrointestinal tract |

| Inflammation | Mucosal involvement only | Transmural involvement |

| Microscopic Changes | Crypt abscess formation Reduced goblet cells Non-granulomatous |

Granulomatous (non-caseating) |

| Macroscopic Changes | Continuous inflammation (proximal from rectum) Pseudopolyps and ulceration |

Discontinuous inflammation (‘skip lesions’) Fissures and deep ulcers (‘cobblestone appearance’) Fistula formation |

Table 1 – Characteristic Features of Inflammatory Bowel Disease

Risk Factors

The aetiology of Crohn’s disease is unknown, however both environmental factors and genetic factors are involved.

The main known risk factors for Crohn’s disease include strong family history (20% have first degree relative affected) and smoking (increases both the risk of developing Crohn’s disease and the risk of relapse)

Clinical Features

Crohn’s disease typically presents with episodic abdominal pain and diarrhoea. The abdominal pain may be colicky in nature and will vary in site depending on the region of bowel involved. Diarrhoea is often chronic and may contain blood or mucus.

Systemic symptoms include malaise, anorexia and low-grade fever. It may also result in clinical features of malabsorption and malnourishment if severe, albeit typically a late presenting feature (in children, this may initially present as a failure to grow or thrive).

As the disease affects the entire gastrointestinal tract, both oral aphthous ulcers (Fig.1) and perianal fistulating disease can occur.

Figure 1 – Aphthous oral ulcer in active Crohn’s disease

Extra-Intestinal Features

Crohn’s disease, much like Ulcerative Colitis, is associated with several extra-intestinal manifestations of the disease:

- Musculoskeletal, such as enteropathic arthritis (typically affecting sacroiliac and other large joints), nail clubbing, or metabolic bone disease (secondary to malabsorption)

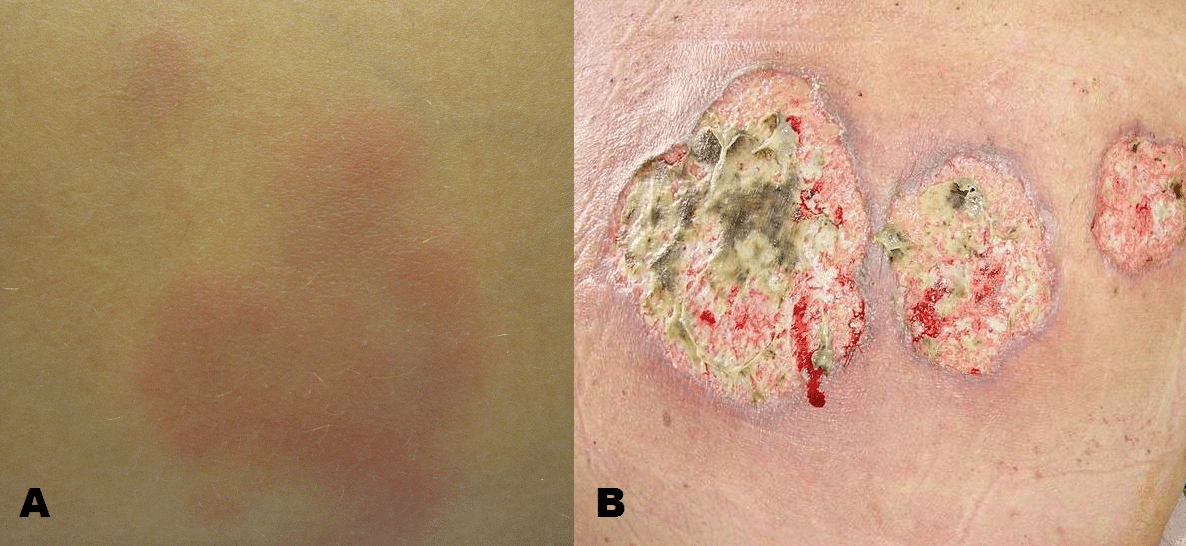

- Skin, such as erythema nodosum (tender purple subcutaneous nodules, typically on the shins (Fig. 2A)) or pyoderma gangrenosum (erythematous papules or pustules that develop into deep ulcers (Fig. 2B))

- Eyes, such as episcleritis, anterior uvetitis, or iritis

- Hepatobiliary, such as Primary sclerosing cholangitis (albeit more associated with ulcerative colitis), cholangiocarcinoma (due to association with primary sclerosing cholangitis), or gallstone disease (see Complications)

- Renal– Renal stones (see Complications)

Investigations

For patients with a suspected diagnosis of Crohn’s disease, routine blood tests can be performed, to assess for evidence of any anaemia, low albumin (secondary to systemic illness), or evidence of inflammation (raised CRP and WCC).

A faecal calprotectin test should be performed in all patents with recent onset lower gastrointestinal symptoms, with a good sensitivity for inflammatory bowel disease. A stool MC&S sample should be sent to exclude an infective cause.

Colonoscopy is the gold standard investigation. Endoscopic views will show evidence of any inflammation, and can be biopsies taken to confirm the diagnosis (Table 1).

Severity Classification

The Montreal Score can be used to classify disease severity of Crohn’s disease

- Age at diagnosis

- A1 = below 16yrs; A2 = between 17yrs and 40yrs; A3 = above 40yrs

- Location

- L1 = ileal; L2 = colonic; L3 = ileocolonic; L4 = isolated upper disease

- Behaviour

- B1 = non‐stricturing & non‐penetrating; B2 = stricturing; B3 = penetrating

- Add a “p” if concurrent perianal disease is present

Imaging

MRI small bowel imaging can be used to assess and monitor small bowel involvement and severity. Any active inflammation or fistulating disease can be assessed for using MRI imaging.

In cases without any colonic or terminal ileal disease, where biopsies may be amenable, a presumed diagnosis can be made on clinical features and imaging alone.

MRI imaging of the rectum can be used to assess for fistulating perianal disease. If needed, an Examination Under Anaesthesia (EUA) may then be be considered to examine and treat any perianal fistulae present.

In the acute setting, patients with Crohn’s disease may often require urgent CT imaging to assess for any evidence of bowel obstruction (from stricturing disease) or bowel perforation (from full thickness penetrating disease).

Management

Any patients with suspected inflammatory bowel disease should be referred to Gastroenterology for confirmation of the diagnosis and initiation of treatment.

Complex disease presentations may warrant discussion in a specific IBD MDT meeting, with involvement of Gastroenterology, General Surgery, Radiology, IBD specialist nurses, Dieticians, and multiple other allied healthcare professionals.

Patients in acute flares of the disease will often need an acute hospital admission, to treat the disease and attempt disease remission.

Inducing Remission

Patients in an acute flare of Crohn’s disease will require starting corticosteroid therapy as first line to induce remission

Ensure patients also receive adequate fluid resuscitation and prophylactic heparin with anti-embolic stockings (due to the prothrombotic state of IBD flares). Low residue diets should be provided,

If patients fail first line therapy, immunosuppresive agents, such as mesalazine or azathioprine, or biological agents, such as infliximab or adalimumab, can be trialled as subsequent therapy if then needed.

As a general rule, anti-motility drugs, such as loperamide, should be avoided in acute attacks, as these can precipitate toxic megacolon.

Maintaining Remission

Azathioprine is recommended as a monotherapy to maintain remission as first line. Methotrexate can also be considered as an alternative agent for inducting remission. Smoking cessation is advised where applicable.

Patients should be referred to IBD nurse specialists and patient support groups. Enteral nutritional support should be considered, especially in young patients with growth concerns; low residue diets can often be beneficial

Due to increased risk of colorectal malignancy, colonoscopic surveillance is offered to people who have had the disease for >10 years with >1 segment of bowel affected (follow-up time frame depends on risk stratification of disease following initial endoscopy).

Surgical Management

Around 70-80% of Crohn’s patients require surgery at some point in their lifetime.

Surgical intervention is indicated in those with failed medical management or have developed severe complications (such as strictures or perforation), both in the emergency and elective setting. In all proposed operations, a bowel-sparing approach must be taken to prevent short gut syndrome in later years.

Common operations that are required in patients with Crohn’s disease include:

- Ileocaecal resection(removal of terminal ileum and caecum with primary anastomosis)

- Small bowel resection

- Surgery for peri-anal disease (e.g. abscess drainage, seton insertion, or laying open of fistulae)

- Stricturoplasty (division of a stricture that is causing bowel obstruction)*

Crohn’s disease patients are typically high risk patients to operate on, therefore pre-operative optimisation (including treating any acute attack and managing nutrition) should be attempted where possible.

In those with an active severe flare, a primary bowel anastomosis should not be performed (or at least not without a defunctioning stoma), due to the risk of breakdown at the anastomosis

*Balloon dilation can also be considered in patients with a single stricture that is short and straight, and accessible by colonoscopy

Complications

Gastrointestinal

- Fistula, including enterovesical, enterocutaneous, or rectovaginal fistula

- Stricture formation

- Recurrent perianal fistula, often difficult to treat and can result in perianal sepsis (i.e. perianal abscess formation)

- Gastrointestinal malignancy, as patients with Crohn’s disease have about a 3% risk of developing colorectal cancer over 10 years and small bowel cancer is about 30x more common in those with Crohn’s disease

Extraintestinal

- Malabsorption, including growth delay in children, and osteoporosis, secondary to malabsorption or long-term steroid use

- Increased risk ofgallstones, due to reduced reabsorption of bile salts at the terminal ileum

- Increased risk of renal stones, due to malabsorption of fats in the small bowel which causes calcium to remain in the lumen; oxalate is then absorbed freely (as normally bound to calcium and excreted in stool), resulting in hyperoxaluria and formation of oxalate stones

Key Points

- Crohn’s disease can affect any part of the gastrointestinal tract, with the most common site affecting being the terminal ileum

- Definitive diagnosis is made from colonoscopy and biopsy

- Medical management of acute flares involves sequential escalation of treatment, from corticosteroids and immunosuppressors to biological therapies

- Surgical input should be sought urgently in cases refractory to medical management