Introduction

A gastrointestinal perforation can occur at any anatomical location of the alimentary canal, from the upper oesophagus to the anorectal junction.

Delay in resuscitation and definitive surgery of any perforation will progress rapidly into septic shock, multi organ dysfunction, and death, hence it should be one of the first diagnoses considered in all patients who present with acute abdominal pain.

In this article, we shall look at the causes, clinical features, and management of gastrointestinal perforation, mainly focusing on those patients presenting with a bowel perforation.

Aetiology

There are multiple causes of gastrointestinal perforation, varying dependent on the location of the GI tract involved:

- Upper GI tract

- Peptic ulcer disease

- Gastric cancer or oesophageal cancer

- Foreign body ingestion (e.g. battery or caustic soda)

- Excessive vomiting (Boerhaave Syndrome)

- Lower GI tract

- Diverticulitis (most common in higher-income countries)

- Colorectal cancer

- Appendicitis or Meckel’s Diverticulitis

- Foreign body insertion

- Severe colitis, such as Crohn’s Disease

- Toxic megacolon (e.g. from Clostridum Difficile or Ulcerative Colitis)

- Any part of the GI tract

- Iatrogenic, such as during gastroscopy or colonoscopy

- Trauma, either through penetrating or blunt mechanisms

- Mesenteric ischaemia

- Obstructing lesions (e.g. cancer, bezoar, or faeces/sterocoral), leading to bowel obstruction, with subsequent ischaemia and necrosis

Clinical Features

The main feature of gastrointestinal perforation is abdominal pain. Typically this is rapid onset and severe. Patients are systemically unwell and may also have associated malaise, vomiting, or lethargy. Further symptoms will be dependent on the underlying cause

The degree of how unwell a patient is with gastrointestinal perforation is dependent on multiple factors, such as the type of perforation, timing of presentation, and patient co-morbidities and functional status

On examination, patients will look unwell and often have features of sepsis. They will usually have features of peritonism, which may be localised or generalized (a rigid abdomen); generalised peritonitis implies diffuse contamination of the abdomen and the patient will be very unwell.

Thoracic Perforation

Any thoracic region perforation (such as a oesophageal rupture) will present with pain, ranging from chest or neck pain to pain radiating to the back, typically worsening on inspiration. There may be associated vomiting and respiratory symptoms.

On examination, auscultation and percussion may reveal signs of a pleural effusion, with the potential for palpable crepitus. This is discussed in more detail here.

Investigations

Laboratory Tests

Any patient with an acute abdomen will require urgent blood tests, including FBC, U&Es, LFTs, CRP, clotting, and G&S.

Patients will have raised inflammatory markers (WCC and CRP). Depending on how unwell the patient is at time of presentation, blood tests may also show evidence of organ dysfunction (such as acute kidney injury or a coagulopathy), developing secondary to sepsis.

Imaging

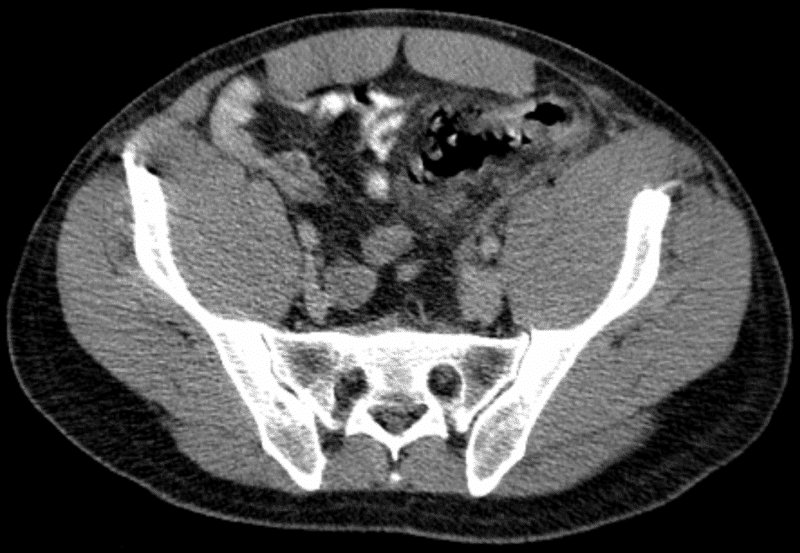

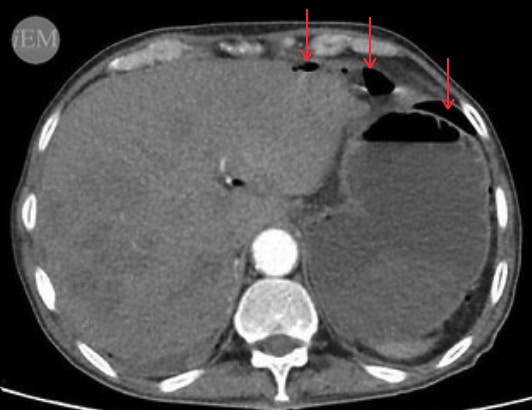

The gold standard for diagnosis of any perforation is with a CT scan with intravenous contrast (Fig. 2) confirming the presence of free air and suggesting a location of the perforation (as well as a possible underlying cause). In cases of suspected upper GI perforation, a CT scan with oral contrast may be used, for better assessment.

Figure 2 – CT scan showing a patient with perforated sigmoid diverticulitis

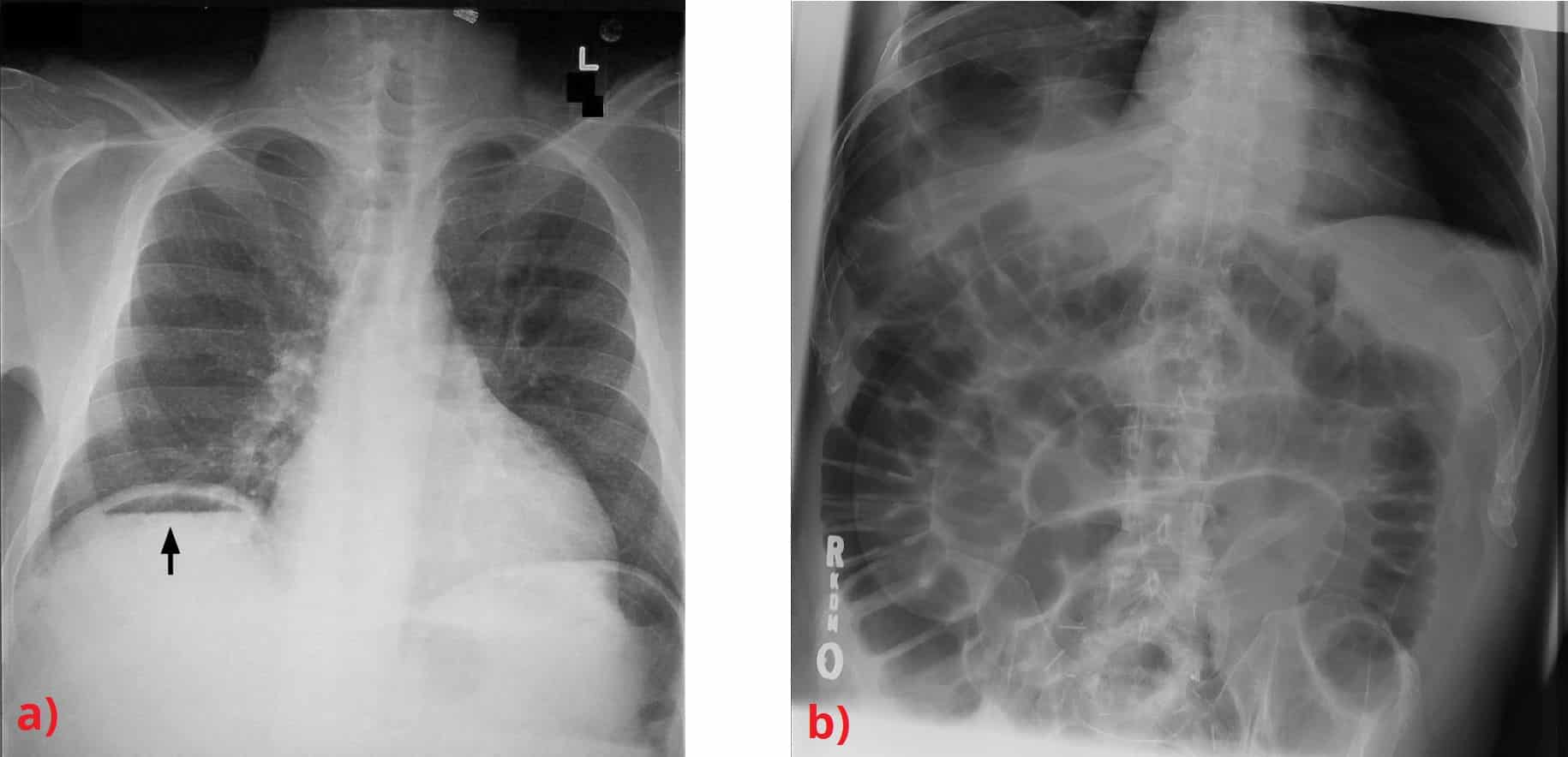

Classically, both a plain film erect chest radiograph (eCXR) and abdominal radiograph (AXR) were used for diagnosis, however are much less specific* compared to CT imaging. As such, in suspected cases, a CT scan should always be performed.

*The sensitivity in detecting perforation on eCXR is around 70%, meaning 3 out of every 10 patients with a gastrointestinal perforation will have no signs on plain film radiograph

CXR and AXR Features

An eCXR may show air under the diaphragm in cases of pneumoperitoneum (Fig. 3a), whilst an AXR may show either Rigler’s sign (both sides of the bowel visible, Fig. 3b), or psoas sign (loss of the sharp delineation of the psoas muscle border)

Management

The management of any suspected gastrointestinal perforation warrants an early resuscitation, prompt diagnosis, and definitive treatment.

Broad spectrum antibiotics should be started early. Patients should be placed nil by mouth (NBM) and a nasogastric tube inserted if required. Provide adequate intravenous fluid resuscitation and appropriate analgesia.

Following this standard initial approach, management becomes highly individualised, taking into account the site of perforation and patient factors. Most patients with a perforated viscus will require theatre for repair and control of contamination.

Figure 4 – CT scan showing free intra-peritoneal gas (arrows)

Surgical Intervention

The key aspects of any surgical intervention for a GI perforation are:

- Identification of the underlying cause

- Appropriate management of perforation

- Thorough washout

The surgical technique employed varies depending on the pathology and the anatomical location involved. The most important aspect of any surgery for perforation however remains the intra-operative washout

- Peptic ulcer perforation can be accessed typically either open or laparoscopically and a patch of omentum (termed a “Graham patch”) is tacked loosely over the ulcer

- Small bowel perforation should be managed with a bowel resection +/- primary anastomosis +/- stoma formation; on occasion, small perforations (e.g. a fish bone perforation) can be managed by oversewing the defect

- Large bowel perforation can result in a large amount of contamination, therefore if surgery is warranted then a bowel resection +/- stoma formation is typically the preferred option

Conservative Management

Select physiologically well patients with a gastrointestinal perforation may be managed conservatively, including patients with:

- Localised diverticular perforation with only localised peritonitis and tenderness, and no evidence of generalised contamination

- Patients with a sealed upper GI perforationon CT imaging without generalised peritonism

- Elderly frail patients with extensive co-morbidities who would be very unlikely to survive surgery

Key Points

- Early recognition, prompt resuscitation, and definitive treatment is essential

- CT scans are the imaging modality of choice to confirm the diagnosis of perforation

- Most patients require urgent surgery, however selected physiologically well patients without generalised peritonitis may be managed conservatively

- Key surgical aspects for intervention of a perforation are (1) washout (2) locate underlying cause (3) suitable management of perforation