Introduction

A hernia is defined as the protrusion of a whole or part of an organ through the wall of the cavity that normally contains it into an abnormal position.

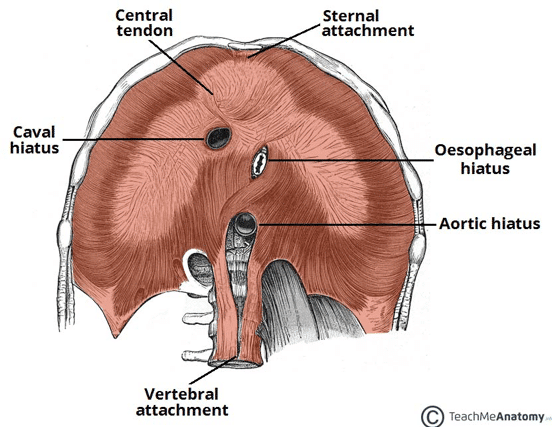

A hiatus hernia describes the protrusion of an organ from the abdominal cavity into the thorax through the oesophageal hiatus (Fig. 1). This is typically the stomach herniating, although less commonly other structures, such as small bowel, colon, or omentum can herniate through. Other types of diaphragmatic hernia also exist.

Hiatus hernias are extremely common, however the exact prevalence in the general population is difficult to accurately state, simply because the majority are completely asymptomatic. It is estimated that around a third of individuals over the age of 50 have a hiatus hernia.

Classification

The anatomical classification of hiatus hernia consists of:

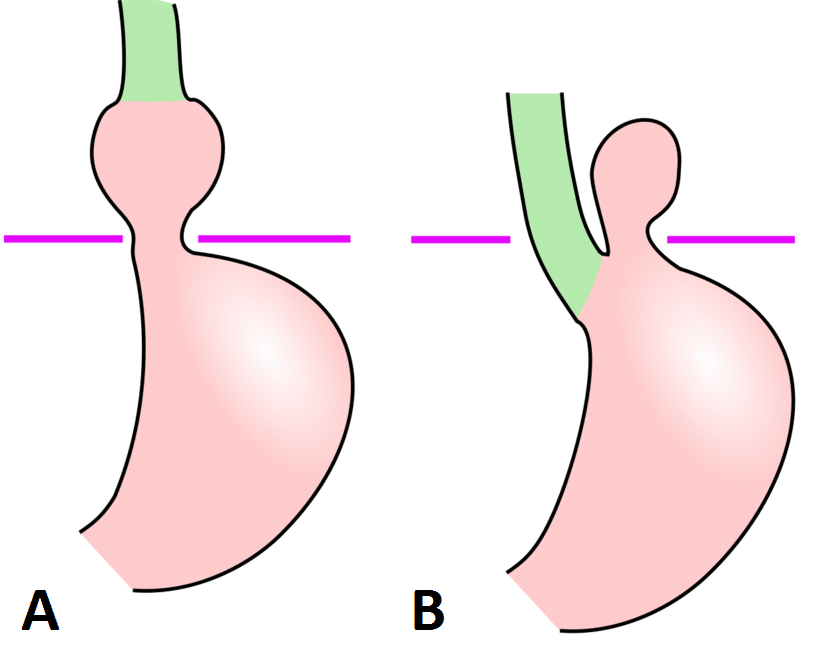

- Type I, Sliding Hernia (90%) – the gastro-oesophageal junction (GOJ), the abdominal part of the oesophagus, and frequently the cardia of the stomach move (or “slides”) upwards through the diaphragmatic hiatus into the thorax (Fig. 2A)

- Type II, Rolling Hernia (or para-oesophageal) – an upward movement of the gastric fundus occurs to lie alongside a normally positioned GOJ, which creates a ‘bubble’ of stomach in the thorax. This is a true hernia with a peritoneal sac (Fig. 2B)

- Type III, Mixed Type – both the gastric fundus and the GOJ herniate above the hiatus, with the fundus lying above the GOJ

- Type IV, Other Structures – other structures apart from the stomach herniating through the oesophageal hiatus

Sliding hernia are frequently associated with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD). Types II-IV are all forms of paraoesophageal hernias, and have a higher risk of gastric ischaemia or volvulus.

Gastric Volvulus

A gastric volvulus can also occur whereby the stomach twists on itself by 180 degrees, leading to obstruction of the gastric passage and tissue necrosis, and requires prompt surgical intervention.

Clinically, this can present with Borchardt’s triad: (1) sudden severe epigastric pain (2) retching without vomiting (3) inability to pass a nasogastric tube.

An urgent CT scan is required and often needing emergency surgery

Risk Factors

Age is the main risk factor for developing a hiatus hernia, due to a combination of age-related loss of diaphragmatic tone, increasing intrabdominal pressures (e.g. repetitive coughing), and an increased size of diaphragmatic hiatus.

Pregnancy, obesity, and ascites are also risk factors, due to increased intra-abdominal pressure and superior displacement of the viscera. Previous oesophageal and stomach surgery also increase the risk of developing hiatus hernia, due to the disruption to the oesophageal hiatus.

Clinical Features

The vast majority of hiatus hernias are completely asymptomatic.

For those with symptoms, the majority present with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease, mainly epigastric pain, made worse by lying flat. These symptoms often do not fully resolve with treatment.

Less common symptoms include hiccups or palpitations (due to irritation of the diaphragm or pericardial sac), vomiting, swallowing difficulties, or anaemia (secondary to oesophageal ulceration or bleeding from gastric body in hernia*)

The clinical examination is typically normal. In patients with a sufficiently large hiatus hernia, bowel sounds may be auscultated within the chest.

In rare cases, large hiatus hernia can result in gastric outflow obstruction, presenting with early satiety, vomiting, and severe chest pain.

*Cameron lesions are a rare cause of upper GI bleeding that is localised to the gastric body mucosa of patients with large hiatus hernia

Differential Diagnosis

Important differentials for non-specific epigastric pain includes ischaemic heart disease, gastric malignancy, pancreatic malignancy, or gallstone disease.

Investigations

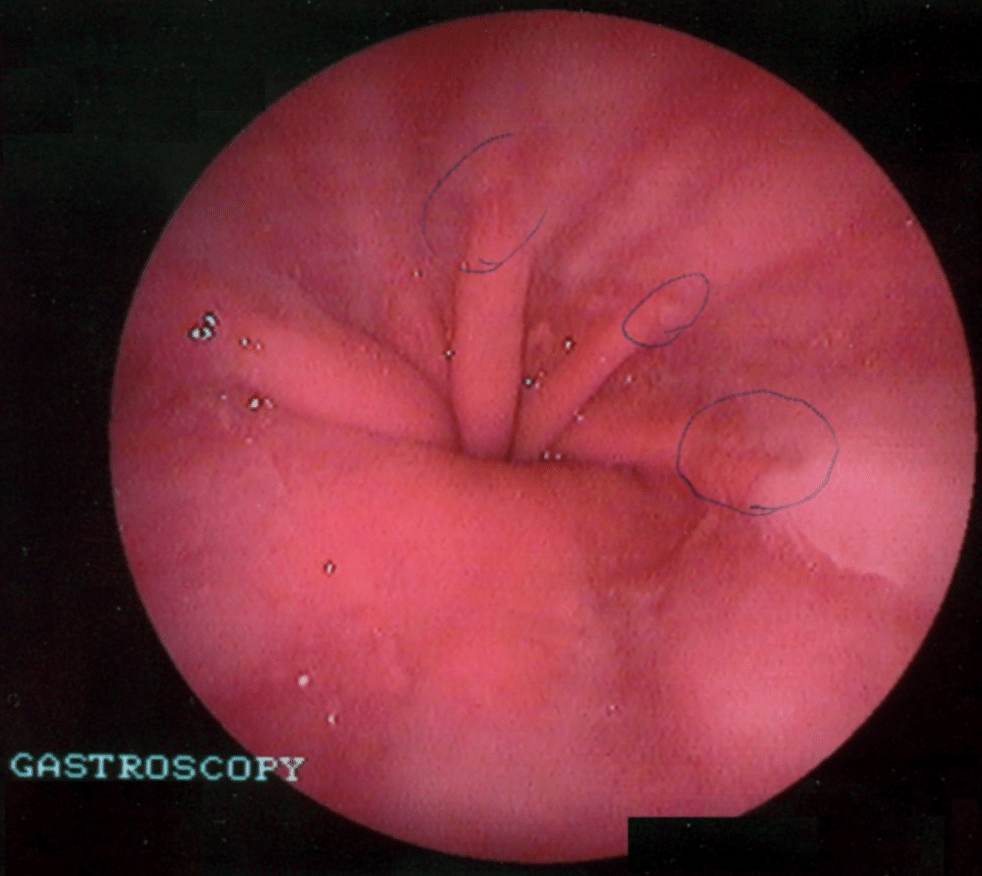

The majority of cases are diagnosed on upper GI endoscopy (OGD), as the most common symptom is reflux or epigastric pain. OGD can show an upward displacement of the GOJ (Fig. 4, also termed the ‘Z-line’), as well as any oesophagitis, gastritis, or Barrett’s oesophagus present (and exclude any malignancy).

Many hiatus hernia are often diagnosed incidentally, typically on CT imaging. However, if the hiatus hernia is asymptomatic with no significant features on imaging, then no further investigations are usually required.

For patients being considered for surgical management (discussed below), further investigations are often required:

- Oesophageal manometry – measures the pressure within the oesophagus during swallowing, useful for assessment of oesophageal motility disorders, such as achalasia

- Ambulatory 24-hour oesophageal pH monitoring – quantifies the level of reflux and assess the relationship between the reflux episodes and patient symptoms

- Contrast swallow or meal – can be used to diagnose a hiatus hernia and rule out other structural disorders such as strictures or motility disorders

Management

Conservative

The majority of symptomatic patients are started on Proton Pump Inhibitors (PPIs), acting to reduce gastric acid secretion and aiding in symptom control.

Patients should also be advised of lifestyle modification, such as weight loss and alteration of diet (low fat, avoidance of meals 2-3 hours before bedtime, smaller portions).

Smoking cessation and reduction in alcohol intake should be advised, as both nicotine and alcohol are thought to inhibit lower oesophageal sphincter function, thereby worsening symptoms.

Surgical Management

Surgical management is indicated when:

- Ongoing symptoms or complications of GORD (e.g. Barrett’s), despite maximal medical therapy

- Increased risk of complications e.g. obstruction, strangulation, or volvulus

- Para-oesophageal hernias type II-IV more commonly require surgical management when symptomatic as a result

- Nutritional failure (due to gastric outlet obstruction)

For those with indications for surgery, the investigations prior to any surgery should aim to assess the hernia anatomy, confirm no concurrent motility disorders present (as these would need separate treatment), and assess relationship between symptoms and degree of reflux (to ensure operation likely to be effective in controlling symptoms). Any complex cases should ideally be discussed at a benign upper GI MDT.

Hiatus hernia surgery typically involves a cruroplasty followed by a fundoplication, either laparoscopically (more common) or open:

- Cruroplasty – The hernia is reduced from the thorax into the abdomen and the hiatus re-approximated to the appropriate size, usually with sutures; a mesh can be placed in larger cases, however the evidence for their use is limited

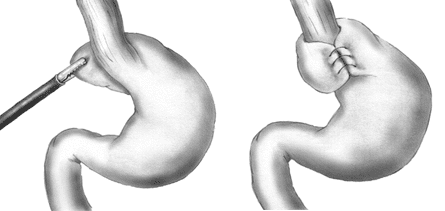

- Fundoplication – The gastric fundus is wrapped around the lower oesophagus and stitched in place (Fig. 5), to strengthen the lower oesophageal sphincter and keep the GOJ in place below the diaphragm

- The wrap can be a full 360 wrap (e.g. Nissen fundoplication) or a partial wrap (e.g. Toupet fundoplication), depending on patient factors and surgeon preference

Figure 5 – Fundoplication, wrapping the fundus of the stomach around the lower oesophagus and suturing in place

Complications of Surgery

The success rate of repair is excellent, with some centres reporting that >90% of patients have a good long term outcome. However, there are specific complications relating to hiatus hernia surgery:

- Recurrence of the hernia, due to failure of the cruroplasty

- Abdominal bloating or increased flatulence, secondary to an inability to belch from the tightness of the wrap

- Dysphagia, if the wrap is too tight or if the crural repair is too narrow, often transient post-operatively due to initial oedema, however if persistent may need revision surgery

- Fundal necrosis, if the blood supply via the left gastric artery and short gastric vessels has been disrupted – this is a surgical emergency and will require gastric resection

Complications

Hiatus hernias, especially the rolling type, are prone to incarceration, obstruction and strangulation.

Key Points

- Hiatus hernia are divided into two main subtypes, sliding (most common) and rolling

- Most hiatus hernia are asymptomatic, however the most common presenting symptom is reflux

- The mainstay of investigation is OGD, however pH monitoring and manometry can also be performed

- Surgical intervention is warranted in patients with ongoing symptoms despite maximal medical therapy, increased risk of complications, or nutritional failure