Introduction

Acute Otitis Media (AOM) presents over a course of days to weeks, typically in young children, characterised by severe otalgia and visible inflammation of the tympanic membrane. The patient may also have systemic features, such as fever and malaise.

Although AOM is a common condition in young children, it can affect all age groups, including neonates. Importantly, however, in school age children recurrent episodes can lead to time out of education and the potential to develop chronic issues, such as hearing loss and developmental delay.

More than two thirds of children will have had at least a single episode of acute otitis media by age 3.

Pathophysiology

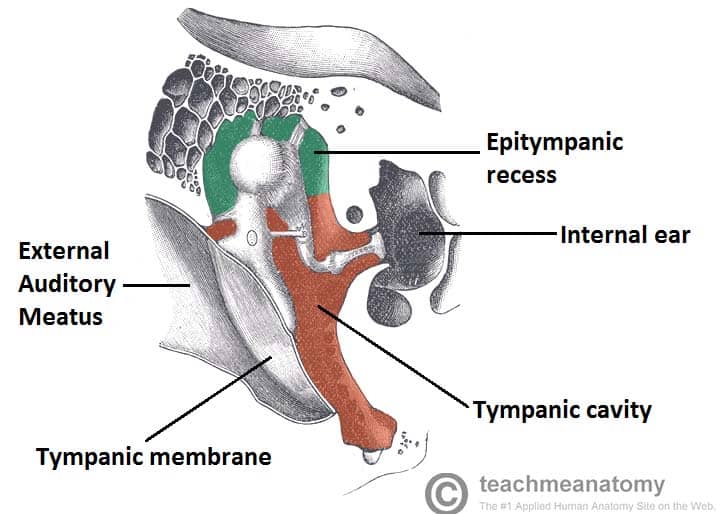

Bacterial infection of the middle ear results from nasopharyngeal organisms migrating into the middle ear cavity via the eustachian tube.

The anatomy of the eustachian tube in younger children is immature, typically being shorter and more horizontal, meaning infection is more likely.

Majority of acute otitis media are secondary to viral infections. Common causative bacteria include S. pneumoniae (most common), H. influenza, M. catarrhalis, and S. pyogenes, all common upper respiratory tract microbiota. Common viral pathogens are respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) and rhinovirus.

Risk Factors

Risk factors for AOM include age (peak age 6-15 months), gender (more common in boys), passive (parenteral) smoking, bottle feeding, and craniofacial abnormalities.

Recurrent AOM (>5 episodes in a year) is seen more commonly with the use of pacifiers, who are typically fed supine, or their first episode of AOM occurred <6months. AOM is most common in the winter season.

Clinical Features

Common symptoms of AOM include pain, malaise, fever, and coryzal symptoms, lasting for a few days. Pain can be difficult to interpret in young children, but they may tug at or cradle the ear that hurts, appear irritable, disinterested in food or present with vomiting.

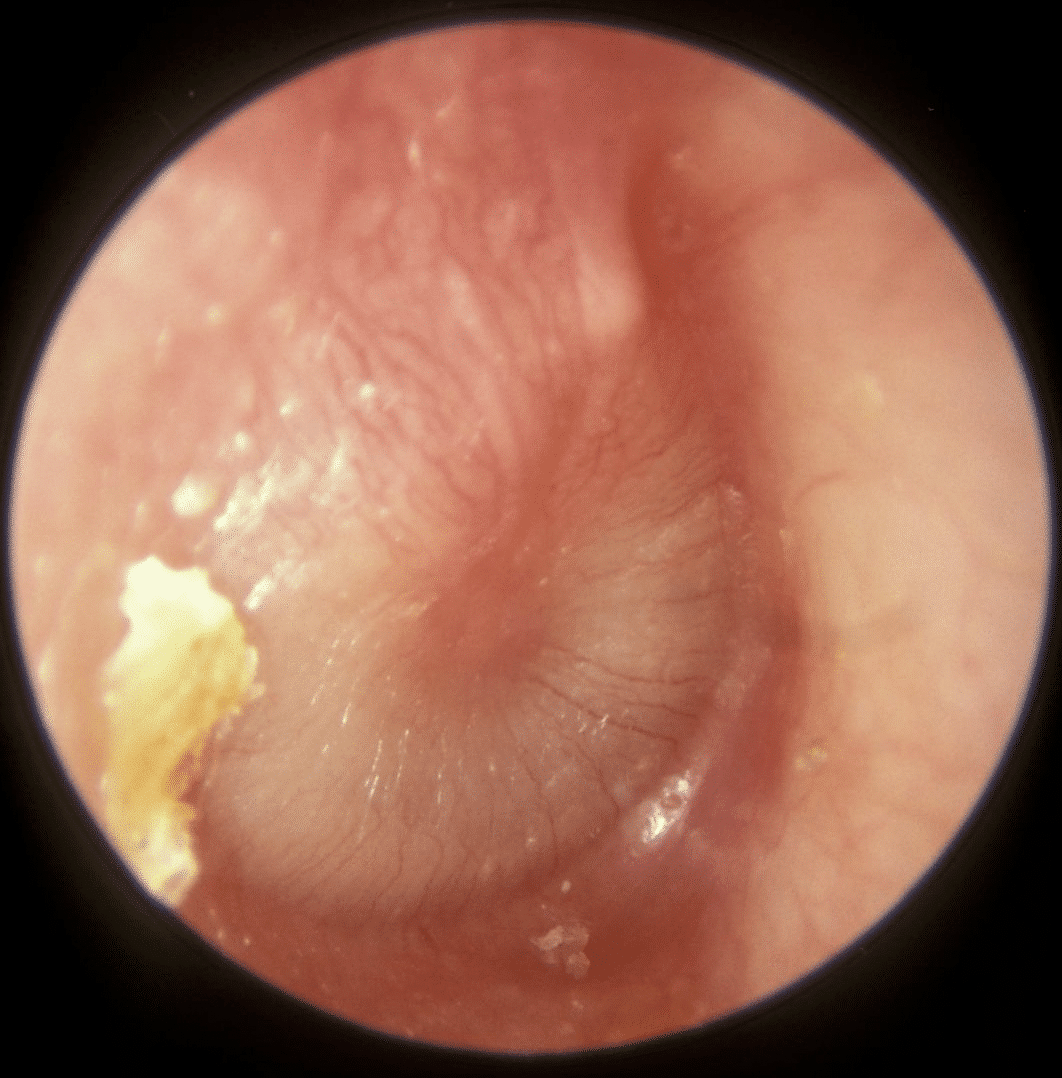

On otoscopy, the tympanic membrane (TM) will look erythematous and may be bulging. If this fluid pressure has perforated the TM*, there may be a small tear visible with purulent discharge in the auditory canal. Patients may have a conductive hearing loss or a cervical lymphadenopathy. Some patients will have concomitant otitis externa due to irritation of the external auditory canal lining from purulent discharge.

It is important to test and document the function of the facial nerve (due to its anatomical course through the middle ear). Examination should also include checking for any intracranial complications, cervical lymphadenopathy, and signs of infection in the throat and oral cavity.

*Any extreme pain that suddenly resolves, followed by ear discharge is highly suggestive of an episode of acute otitis media.

Differential Diagnoses

The main differentials for AOM are acute infective episode of a patient with Chronic Mucosal Otitis Media, Otitis Media with Effusion (OME), and Otitis Externa (OE).

Investigations

Most cases can be diagnosed clinically. For severe cases, routine blood tests should be sent (including FBC, U&Es, and CRP), to confirm the diagnosis and can be useful to gauge response to treatment. Any discharge from the ear should be sent for fluid MC&S.

Management

The majority of cases of acute otitis media will resolve spontaneously within 24 hours, nearly all within 3 days.

All patients should be treated with simple analgesics in the first instance. There is no need to treat with antibiotics in most cases and a ‘watch and wait’ approach can be taken provided there are no worrying features (as discussed below).

Grommets can also be used to treat select patients with recurrent AOM.

If patient presents with a tympanic membrane perforation, an audiogram can be performed to identify any conductive hearing loss. Most perforations would heal spontaneously within a month.

Antimicrobial Management

Antibiotics can be avoided unless significant deterioration or disease progression is seen, as most of the cases are secondary to viral infection. Oral antibiotics can be considered in cases of:

- Systemically unwell children not requiring admission

- Known risk factors for complications, such as congenital heart disease or immunosuppression

- Unwell for 4 days or more without improvement, with clinical features consistent with acute otitis media

- Discharge from the ear (ensure swabs are taken prior to commencing antibiotic therapy)

- Children younger than 2 years with bilateral infections

- Systemically unwell adult, provided not septic and with no signs of complications

Inpatient admission should be considered for all children under 3 months with a temperature >38c, or aged 3-6 months with a temperature >39c, for further assessment.

Also, consider admission for those with evidence of an AOM complication or the systemically unwell child. Patients with a cochlear implant will need to be seen by a specialist and may require inpatient treatment.

Complications

There are varying complications of AOM, which can be categorised into:

- Intra-temporal – tympanic membrane perforation, facial nerve palsy, hearing loss, chronic mucosal otitis media, and mastoiditis (see below)

- Extra-temporal – Sigmoid sinus thrombosis, Bezold’s abscess, Citelli’s abscess, and Luc’s abscess

- Intracranial – Meningitis, intracranial abscess, and cavernous sinus thrombosis

Mastoiditis

One of the most important complications with AOM to consider is mastoiditis.

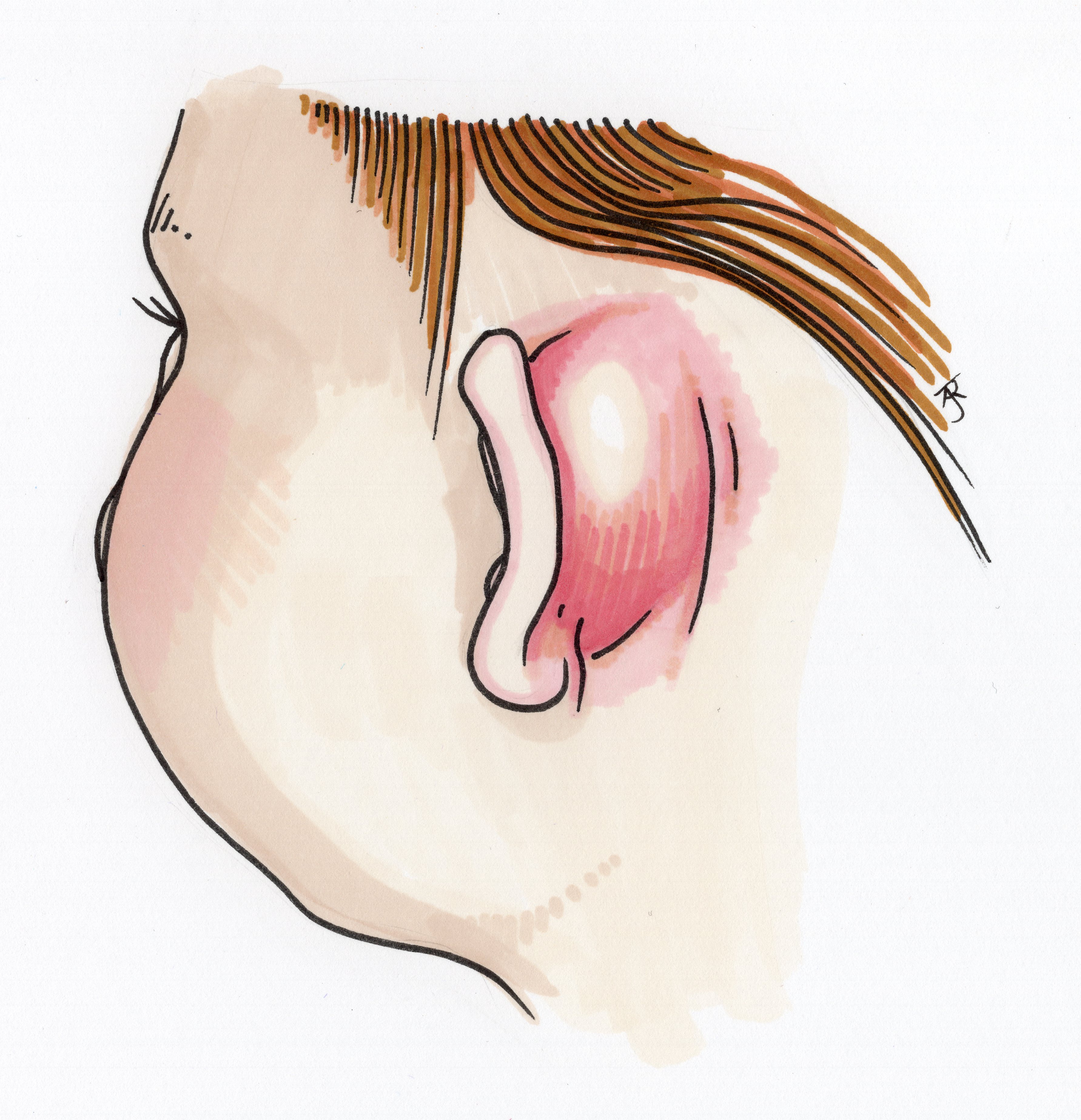

The middle ear and mastoid are one cavity, and as such, there will nearly always be a degree of mastoiditis with AOM. However, if the inflammation within the air cells progresses to necrosis and subperiosteal abscess, this is of significant concern (Fig. 4).

It presents clinically as a boggy, erythematous swelling behind the ear, which if left untreated causes anterior protrusion of the pinna. In children, mastoiditis presents in a similar way.

Any suspected cases should be admitted for intravenous antibiotics and investigated further via CT head if no improvement is seen after 24 hours of intravenous antibiotics.

There is a higher risk of intracranial spread and meningitis, hence cases are often considered for mastoidectomy with grommet insertion as definitive management if there is no improvement with IV antibiotics.

Figure 4 – Mastoiditis, a relatively common complication of AOM

Key Points

- Acute otitis media is a common infection of the middle ear, mostly seen in young children

- Diagnosis is clinical, with most patients having varying degrees of pain, malaise, fever, and coryzal symptoms

- Most cases can be treated conservatively, via simple analgesics and without any antibiotics

- An important complication is mastoiditis, whereby infection spreads to the mastoid air cells