Introduction

Trigger finger, also termed stenosing flexor tenosynovitism is a condition in which a finger or thumb clicks or locks when in flexion, preventing a return to the extended position.

It can affect one or more tendons of the hand, with most cases occurring spontaneously in otherwise healthy individuals.

It has a prevalence of approximately 2 in 100 people. The condition can be associated with other co-morbidities, such as rheumatoid arthritis, amyloidosis, or diabetes mellitus.

In this article, we shall look at the pathophysiology, clinical features and management of trigger finger.

Pathophysiology

Most cases of trigger finger are preceded by flexor tenosynovitis, often from repetitive movements, leading to inflammation of the tendon and sheath.

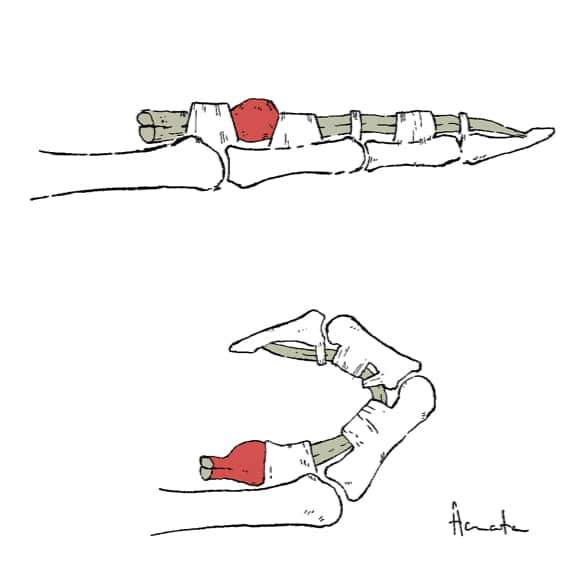

Superficial and deep flexor tendons with localised tenosynovitis at the metacarpal head subsequently develop nodal formation on this location on the tendon, distal to the pulley (Fig. 1). The A1 pulley (see below) is the most frequently involved ligament in trigger finger.

When the fingers are flexed, the node moves proximal to the pulley, however when the patient attempts to extend the digit this node fails to pass back under the pulley. Consequently, the digit becomes locked in a flexed position.

Figure 1 – Illustration demonstrating the pathophysiology of trigger finger

The Flexor Sheath and Pulley System

The flexor sheath and pulley system of the digits ensures the flexor tendons remain in the joint’s axis of motion and prevents bowstringing.

There are three types of pulleys involved:

- Palmar aponeurosis – arises from the palmar aponeurosis and is made up of transverse fascicular bands

- Annular ligaments (5 in total) – A2 and A4 prevent bowstringing of the tendon, whilst A1, A3, and A5 overlie the metacarpophalangeal, proximal interphalangeal, and distal interphalangeal joints respectively

- Cruciate ligaments (3 in total) – prevent collapsing and expansion of the sheath during movement of the digits

Risk Factors

The main risk factor for developing trigger finger is having an occupation or hobby that involves prolonged gripping or repetitive use of the hand.

Other risk factors include certain co-morbidities (such as rheumatoid arthritis, amyloidosis, and diabetes mellitus), female gender, and increasing age.

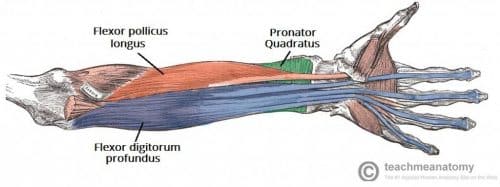

Figure 2 – Deep flexor muscles of the anterior forearm, forming some of the flexor tendons

Clinical Features

Patients with a trigger finger will often initially report a painless clicking, snapping, or catching when trying to extend their finger. It most commonly affects the middle or ring finger. More than one finger can be involved at a time and it may be bilateral.

Over time, this may become painful, especially over the volar aspect of the metacarpophalangeal joint, and the digit can lock in a flexed position.

On examination of the hand, the proximal aspect of the phalanx should be palpated to assess for any clicking, pain associated with movement, and any lumps or masses.

Differential Diagnoses

The main differentials to consider include:

- Dupuytren’s contracture– whilst the flexion is painless, it is typically fixed and cannot be passively corrected

- Infection– any infection within the tendon sheath is a surgical emergency; this usually is preceded with localised trauma and the finger becomes swollen, erythematous, and painful

- Ganglion– involving a tendon sheath

- Acromegaly– excessive growth hormone results in swelling of flexor synovium within tendon sheath due to increased extracellular volume, limiting both flexion and extension in the affected digit

Investigations

The diagnosis of trigger finger is clinical. Blood tests or imaging may be warranted if any of the above differentials are suspected.

Management

Mild cases of trigger finger can be managed conservatively. Advice regarding activities that cause pain should be given and a small splint can also be used to hold the finger in the extension position at night (this keeps the roughened portion of the tendon in the tunnel which makes it smoother)

For those that do no response to conservative management or are severe, steroid injections can be trialled, which can show improvement over a few days.

Surgical Management

A percutaneous trigger finger release via a needle can be attempted in most cases, involving the release of the tunnel using a needle, performed under local anaesthetic.

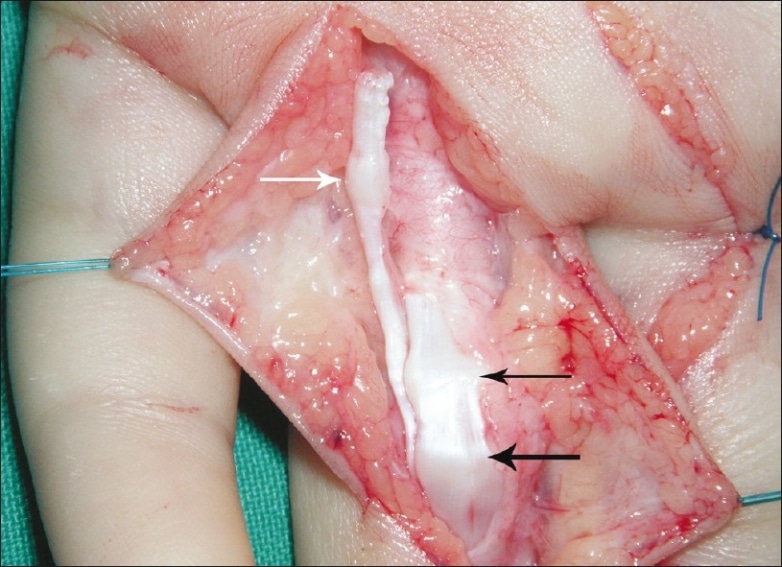

For severe cases, surgical decompression of tendon tunnel can be trialled (Fig. 3), whereby the roof of the tunnel is slit, in turn widening its mouth to release the tendon. This can be performed under either a local or general anaesthetic.

Complications

Recurrence of triggering following surgery is uncommon, however adhesions can form if the patient does not begin immediate motion following surgery.

Key Points

- Trigger finger is caused by a localised nodal formation on the tendon, often following cases of tenosynovitis

- It presents with a painless clicking, snapping, or catching of the affected digit when attempting extension

- Management is often conservative initially, however may require surgical management if there is no improvement or a significant impact on quality of life