Introduction

Haematuria is the presence of blood in the urine, either visible (seen by the naked eye) or non-visible (confirmed by urine dipstick or urine microscopy).

It is never a normal finding and has a range of urological and non-urological causes, both malignant and benign, which commonly require further investigation.

Approximately 14% of patients presenting with visible haematuria and 3% of patients presenting with non-visible haematuria are found to have an underlying malignancy, however this is significantly less in patients aged <45yrs old.

Classification

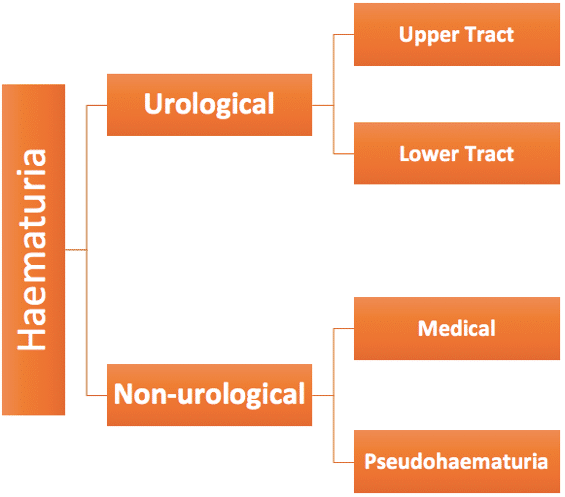

Haematuria is classified into:

- Visible haematuria (VH): formerly ‘macroscopic’ or ‘gross’ haematuria; blood is visible in the urine, colouring it pink, red, or dark brown

- Non-visible haematuria (NVH): formerly ‘microscopic’ or ‘dipstick positive’; blood is present in the urine on urinalysis, but not visible. This can be further categorised into:

- Symptomatic non-visible haematuria (s-NVH): haematuria (confirmed on urinalysis/microscopy) presents with associated symptoms, such as suprapubic pain or renal colic

- Asymptomatic non-visible haematuria (a-NVH): haematuria (confirmed on urinalysis/microscopy) with no associated symptoms

Aetiology

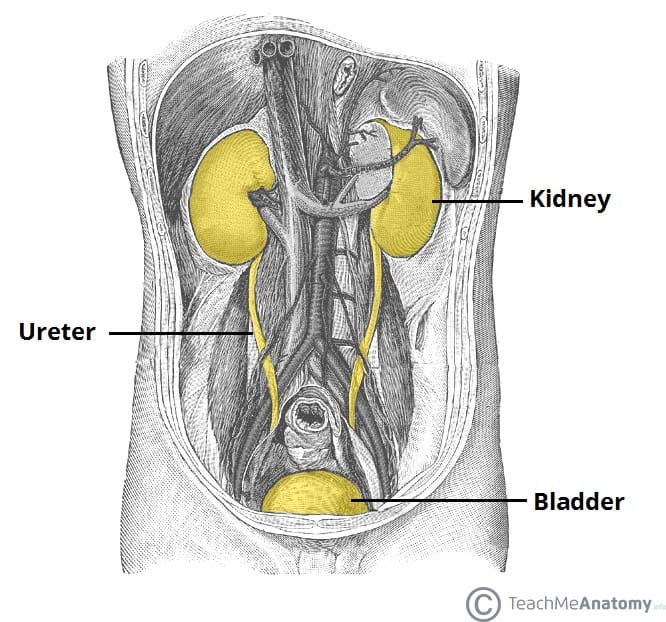

There is a vast array of causes of haematuria, these can be stratified anatomically (Fig. 2).

The most common causes include urinary tract infection (UTI), renal cancer, bladder cancer, renal calculi, prostate cancer, and benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH).

Other less common causes include trauma, radiation cystitis, or parasitic infection (most commonly schistosomiasis). Medical causes for haematuria include glomerulonephritis (such as IgA nephropathy or post-Infectious glomerulonephritis), thin basement membrane disease, haemolytic uraemic syndrome, or multi-system diseases (such as Henoch-Schönlein Purpura or Goodpasteur’s disease)

Pseudohaematuria

Pseudohaematuria is red or brown urine that is not secondary to the presence of haemoglobin.

Causes include medication (such as rifampicin or methyldopa), hyperbilirubinuria, myoglobinuria, and certain foods (such as beetroot or rhubarb)

Clinical Features

The degree of haematuria* should be quantified where possible (e.g. pink vs dark red), and the presence or clots or not. Also enquire about the timing in the stream (as total haematuria suggests as a bladder or upper tract source, whilst terminal haematuria suggests potential severe bladder irritation)

*Bright pink, orange, or dark brown coloured urine may suggest non-urological causes

Clarify any associated symptoms, such as any Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms (LUTS), fevers or rigors, suprapubic pain, flank pain, or weight loss, or recent trauma.

Ensure to assess the drug history* and smoking status, due to the strong association with smoking and urological malignancies. Any exposure to industrial carcinogens (increased risk of bladder cancer) or recent foreign travel (increased risk of schistosomiasis from certain areas) should be clarified.

An abdominal examination is essential, alongside potential Digital Rectal Examination (DRE) and or examination of the external genitalia, depending on the presentation.

*Although patients on anti-platelets or anti-thrombotic agents may have a higher incidence of bleeding on these medications, they should still be investigated as normal

Investigations

Initial Investigations

Urinalysis (urine dipstick testing) is usually the primary investigation in all settings*. The presence of nitrites and/or leukocytes on urinalysis may also indicate infection as a potential underlying cause.

Baseline bloods (FBC, U&Es, and clotting) should be performed. Additionally, prostate specific antigen (PSA) testing may be indicated (after appropriate counselling) in patients where prostatic pathology is considered a possible cause of haematuria.

In those with deranged renal function or suspected of a nephrological cause, urinary protein levels (spot albumin:creatinine ratio or protein:creatinine ratio) may be warranted. Referral to a nephrologist may be warranted in patients with a likely nephrological diagnosis, evidence of declining GFR, severe chronic kidney disease, proteinuria with haematuria, or those <40 years old with hypertension.

*It is worth noting that ‘trace’ blood on a urinalysis does not constitute haematuria – ≥1+ blood is required to constitute haematuria

Urological Referral Criteria for Haematuria

Current NICE guidelines recommend urgent referral to an adult urological service for specialist haematuria investigation in the following:

- Aged ≥45yrs with either:

- Unexplained visible haematuria without urinary tract infection

- Visible haematuria that persists or recurs after successful treatment of urinary tract infection

- Aged 60yrs with have unexplained non‑visible haematuria and either dysuria or a raised white cell count on a blood test.

Patients with asymptomatic non-visible haematuria on two out of three tests should also be referred for further investigation.

Specialist Investigations

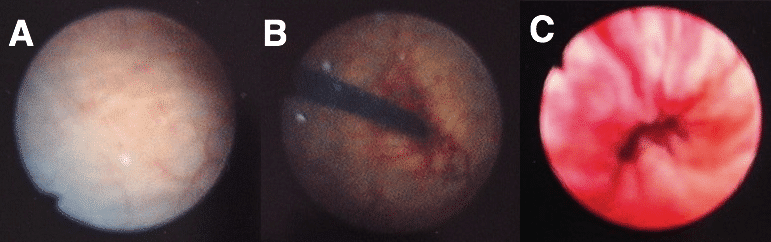

Flexible cystoscopy is the gold standard investigation for assessing the lower urinary tract and should be performed in all cases of haematuria where feasible (Fig. 3). This is often performed under local anaesthetic at a one-stop haematuria clinic.

Whilst more commonly used in follow-up of patients with proven malignancy, some centres will also send urine cytology in the initial assessment for haematuria as a further adjunct assessment.

Figure 3 – Cystoscopy on a 29yr old male, demonstrating (A) normal bladder wall (B) cystoscope entering at the bladder neck (C) an inflamed urethra

Upper urinary tract imaging is also warranted in cases of haematuria:

- Ultrasound imaging of the renal tract is typically performed for cases of non-visible haematuria, and is a cheap and non-invasive method of investigation

- CT Urogram is typically used for cases of visible haematuria, providing often more definitive imaging of the renal tract

Management

Management is treatment of the underlying pathology. Any anticoagulation should be reviewed, any underlying clotting disorders corrected, and blood transfusions performed as required

Patients with significant haematuria, especially those in clot retention (acute urinary retention secondary to clots obstructing the bladder outflow), will need inpatient admission under Urology. These patients will require the insertion of a three-way catheter for ongoing washout and irrigation +/- evacuation of clots.

Rarely, in cases of refractory visible haematuria, especially in patients needing multiple blood transfusions, rigid cystoscopy +/- proceed under general anaesthesia may be required, in attempt to control the bleeding and treat the underlying cause if possible.

Key Points

- There are a vast array of causes of haematuria, the most common being infection, malignancy and urinary stone disease

- Haematuria can be classified as visible (VH), symptomatic non-visible (s-NVH) or asymptomatic non-visible (a-NVH)

- Referral to specialist services is required for all patients with VH and s-NVH, and some patients with a-NVH depending on the results of other baseline investigations

- Flexible cystoscopy is the gold standard investigation for assessing the lower urinary tract