Introduction

Oesophageal motility disorders are a group of conditions characterised by abnormalities in oesophageal peristalsis.

They typically manifest with difficulty swallowing solids and liquids together, and are less common that inflammatory or malignant conditions of the oesophagus.

In this article, we shall look at the two major causes of oesophageal dysmotility, achalasia and diffuse oesophageal spasm.

Oesophageal Anatomy and Physiology

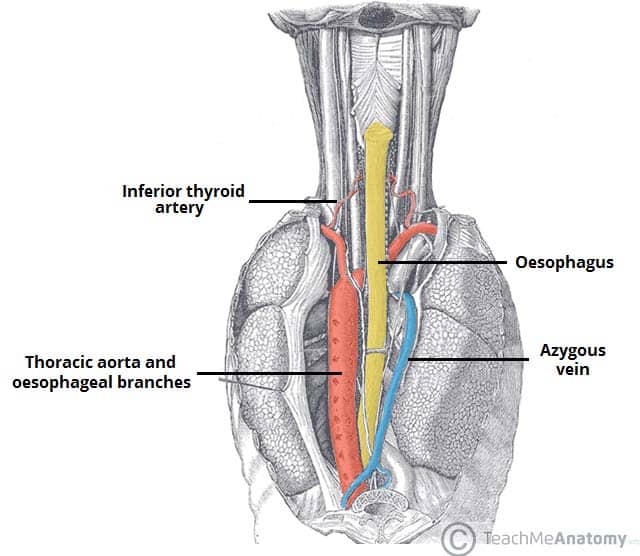

The oesophagus is a 25cm long tube (Fig. 1) and can be divided into thirds:

- Upper third – composed of skeletal muscle

- Middle third – transition zone of both skeletal and smooth muscle

- Lower third – composed of smooth muscle

The upper oesophageal sphincter is comprised of skeletal muscle and prevents air from entering the alimentary canal. The lower oesophageal sphincter (LOS) is composed of smooth muscle and prevents reflux from the stomach.

Peristaltic waves, controlled by the oesophageal myenteric neurones, propel ingested food down the oesophagus. The primary wave is under control of the swallowing centre and the secondary wave is activated in response to distention.

As food descends the oesophagus, the lower oesophageal sphincter relaxes and allows food to pass.

Differential Diagnosis

The main differential diagnoses for oesophageal motility disorders include gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD) and oesophageal malignancy.

Due to their variable and often atypical presentation, often patients are investigated for a number of other pathologies, before an oesophageal motility disorder is diagnosed.

Achalasia

Achalasia is a primary motility disorder of the oesophagus, characterised by a failure of relaxation of the lower oesophageal sphincter and the absence of peristalsis along the oesophageal body.

It is a relatively rare condition (incidence of 1 per 100,000) with a mean age of diagnosis at ~50yrs. The pathophysiology of achalasia is poorly understood, but a common histological feature is the progressive destruction of the ganglion cells in the myenteric plexus.

Patients with long standing achalasia have an x8-16 increased risk of oesophageal cancer, although the absolute risk remains low.

Clinical Features

Patients with achalasia will typically present with progressive dysphagia when ingesting both solids and liquids, as well as the regurgitation of food. The symptom severity frequently varies day-to-day.

Other symptoms include respiratory complications (either a nocturnal cough or aspiration), chest pain, dyspepsia, and weight loss. Symptoms are often non-specific, therefore there is often a substantial delay to diagnosis.

On examination, there are rarely any obvious signs of note, except for visible weight loss in longstanding cases, secondary to a reduced oral intake.

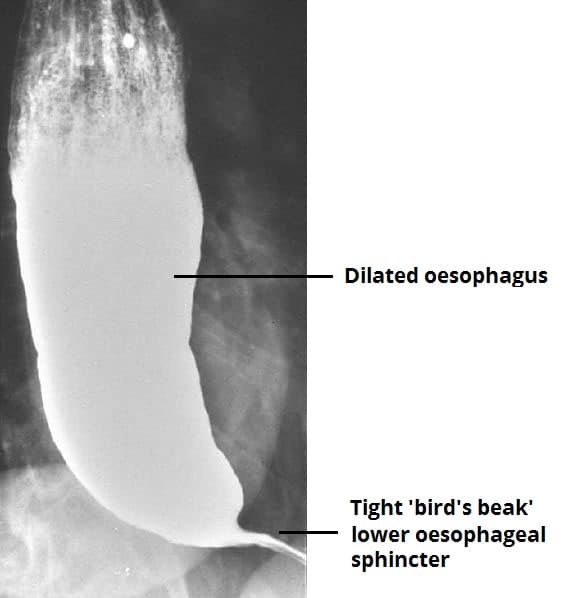

Figure 2 – A barium swallow for a patient with achalasia, giving a “bird’s beak” appearance

Investigation

In any patient presenting with dysphagia, an upper GI endoscopy (OGD) is essential in order to exclude any mechanical cause (including cancer) as the cause of symptoms. In severe cases of achalasia, endoscopy might show a dilated oesophagus with retained food and increased resistance at the GOJ.

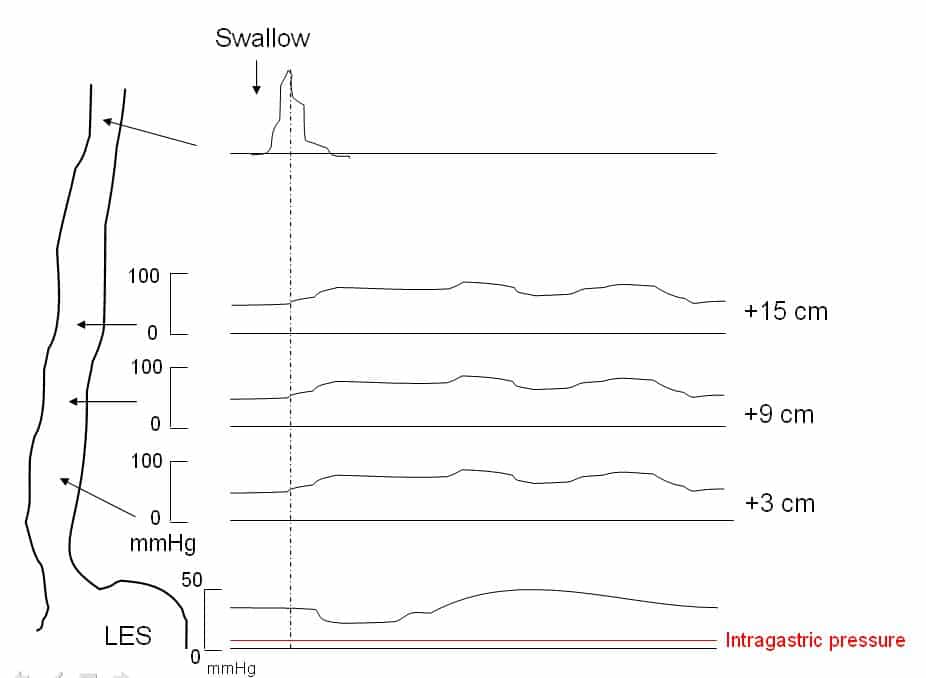

The gold standard in the diagnosis of motility disorders is oesophageal manometry (Fig 3); this procedure involves a pressure sensitive probe inserted into the oesophagus (approximately 5cm proximal to the LOS), which measures the pressure of the sphincter and the surrounding muscle.

In achalasia, the three key features on manometry are:

- Absence of oesophageal peristalsis

- Failure of relaxation of the lower oesophageal sphincter

- High resting lower oesophageal sphincter tone

*Barium swallows are now rarely performed (Fig. 2), but they may show proximal dilation of the oesophagus with a characteristic ‘bird’s beak’ appearance distally (due to the failed dilation of the lower oesophageal sphincter)

Figure 3 – Manometry in achalasia, demonstrating aperistaltic contractions, increased intra-oesophageal pressure, and failure of relaxation of the lower oesophageal sphincter

Classification of Achalasia

High-resolution manometry is increasingly being used to provide more detailed information on oesophageal motility and can provide a sub-classification of achalasia into three groups, based on the pattern of contractility in the oesophageal body (Chicago classification):

- Type I = classical achalasia, 100% failed peristalsis and LOS fails to relax completely

- Type II = Pan-oesophageal pressurisation to > 30mmHg, with at least 20% of swallows, and no normal peristalsis

- Type III = No normal peristalsis, with preserved fragments of distal peristalsis or premature contractions in >20% swallows

Management

The management of achalasia can be divided into medical and surgical management, all aiming to reduce the LOS pressure and relieve the outflow obstruction.

All patients should be given conservative management advice including sleeping with multiple pillows to minimise regurgitation, eating slowly and chewing food thoroughly, and taking plenty of fluids with meals.

Pharmacological options include the use of calcium channel blockers (typically sublingual Nifedipine) to inhibit LOS muscle contraction, however their benefit is often short lived. Botox injections into the lower oesophageal sphincter via endoscopy can be trialled and are often effective, however their effect only lasts for a few months at most.

Surgical Interventions

The main surgical treatments for achalasia are:

- Laparoscopic Heller Myotomy (cardiomyotomy) – the division of the specific fibres of the lower oesophageal sphincter which fail to relax (Fig. 4), with care taken to only divide the muscle fibres and avoid mucosal breach

- A long-term improvement in swallowing is seen in ~85% of patients, with lower side-effect profile compared to endoscopic treatment; reflux becomes a problem after a cardiomyotomy hence a partial fundoplication is usually performed concurrently

- Per Oral Endoscopic Myotomy (POEM) – a cardiomyotomy at the LOS is performed from the inside of the oesophageal lumen, through a submucosal tunnel

- Clinical trials have suggested POEM provides a very good clinical response, especially in patients with a type III pattern of disease, although rates of post-operative GORD are high

- Endoscopic Balloon Dilatation – insertion of a balloon into the lower oesophageal sphincter, which is dilated to stretch the muscle fibres

- It provides a good response in ~90% of patients initially but carries the risks of perforation (~2%) and the need for further intervention; at 5 years, surgery and dilatation are equally successful but 25% of patients require repeat dilatations.

No difference in outcome between Heller Myotomy and Endoscopic Balloon Dilatation has been noted for patients with type I and II achalasia, patients with type III disease seem to respond better to Heller Myotomy than to Endoscopic Balloon Dilatation.

Those with end-stage refractory achalasia may eventually require an oesophagectomy. For select patients where an oesophagectomy is not appropriate, a cardioplasty may be performed although this is rare.

Diffuse Oesophageal Spasm

Diffuse oesophageal spasm (DOS) is a disease characterised by multi-focal high amplitude contractions of the oesophagus.

It is thought to be caused by the dysfunction of the oesophageal inhibitory nerves. In some individuals, DOS can progress to achalasia.

Clinical Features

Patients with diffuse oesophageal spasm will typically present with severe dysphagia to both solids and liquids. Central chest pain is a common finding, usually exacerbated by food.

The pain from DOS can respond to nitrates (due to relaxation of muscle), making it difficult to distinguish from angina pectoris (yet this pain is rarely exertional). As with achalasia, the examination is often normal.

Investigations

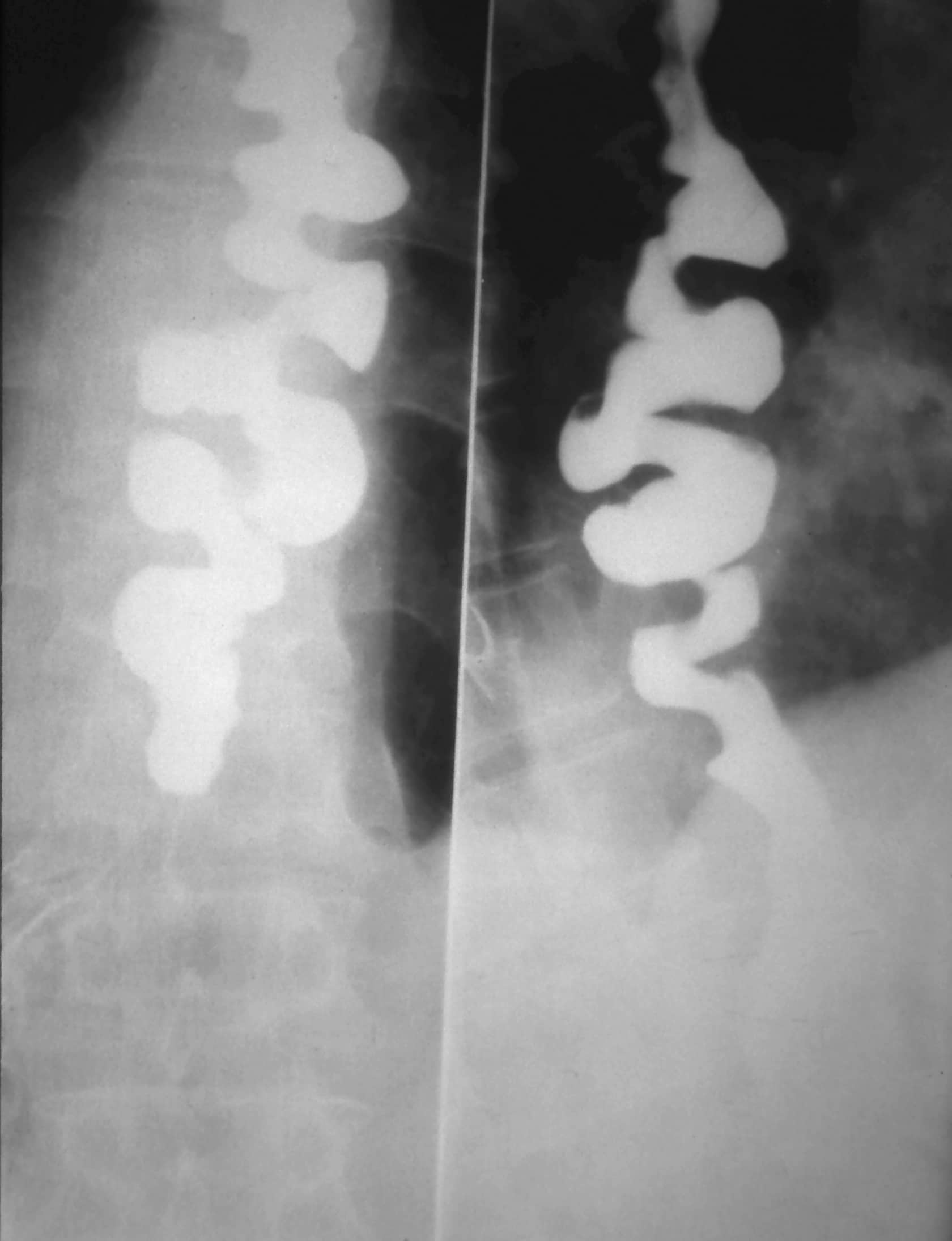

Diffuse oesophageal spasm is investigated in the same manner as other motility disorders, with the definitive diagnosis made via manometry. Endoscopy is usually normal.

Manometry characteristically shows a pattern of repetitive, simultaneous, and ineffective contractions of the oesophagus, as well as potential concurrent dysfunction of the LOS.

Although barium swallow imaging is less commonly performed in current practice, in cases of DOS it can reveal a “corkscrew” appearance (Fig. 5)

Figure 5 – Barium swallow showing a corkscrew appearance, as seen in cases of diffuse oesophageal spasm

Management

The initial management of DOS is through agents which act to relax the oesophageal smooth muscle, typically calcium channel blockers (CCBs) as first line. These limit the strongest contractions, and so provide a symptomatic improvement, however their long-term efficacy is less beneficial.

Pneumatic dilatation or Heller myotomy are surgical options that can be trialled for severe refractory nature, however come with risks and have high rates of recurrence

Other Causes of Oesophageal Dysmotility

A number of autoimmune and connective tissue disorders are associated with oesophageal dysmotility. These include systemic sclerosis (most common), polymyositis, and dermatomyositis.

In these cases, treatment is directed at the underlying cause (e.g. immunosuppression in autoimmune-mediated disease), with nutritional modification and proton pump inhibitors as required.

Key Points

- All patients with dysphagia need an urgent upper GI endoscopy

- Most cases of oesophageal motility disorders can be diagnosed from oesophageal manometry

- Oesophageal motility disorders will be managed conservatively initially in most cases

- Surgical options for achalasia are either endoscopic balloon dilatation, laparoscopic Heller myotomy, or eventually oesophagectomy for end stage disease

- POEM is an emerging endoscopic option for achalasia