Introduction

Pancreatic cancer is the 4th most common cause of cancer-related deaths in the UK. It is rare under 40 years of age, with 80% of cases occurring between 60-80yrs, and unfortunately it is uncommon to be diagnosed early enough for curative treatment.

The most common type of pancreatic cancer is ductal adenocarcinoma, arising from the exocrine portion of the organ and comprises up to 90% of cases. The remaining number can be divided into exocrine tumours (such as pancreatic cystic carcinoma) and endocrine tumours (derived from islet cells of the pancreas) with tumour type greatly affecting prognosis.

Approximately 60%–70% of pancreatic cancer arises in the head of the pancreas, 20%–25% in the body and the tail, and the remaining 10%–20% diffusely involve the pancreas. Tumours located in the body and the tail are more likely to be diagnosed at a more advanced stage, compared to tumours located in the head, as they are less likely to develop obstructive symptoms.

In this article, we shall look at the risk factors, investigations, and management of a patient with pancreatic cancer.

Risk Factors

The major risk factor for pancreatic cancer is advancing age. Other key risk factors including male gender, smoking, and obesity.

Chronic pancreatitis and diabetes mellitus also predispose to pancreatic cancer. A number of genetic conditions significantly increase risk, including BRCA mutation and hereditary non-polyposis colon cancer.

Clinical Features

Pancreatic cancer tends to present at a late stage, largely due to the often vague and non-specific nature of symptoms seen early in the disease process.

At a later stage, specific clinical features can be seen and depend on the site of the tumour:

- Obstructive jaundice – due to compression of the common bile duct (present in 90% of cases at time of diagnosis), typically painless

- Weight loss – due to the metabolic effects of the cancer, or secondary to exocrine dysfunction

- Abdominal pain (non-specific) – due to invasion of the coeliac plexus or secondary to pancreatitis

Less common presentations include acute pancreatitis or thrombophlebitis migrans (a recurrent migratory superficial thrombophlebitis, caused by a paraneoplastic hypercoagulable state).

Late onset diabetes mellitus may be the presenting feature for pancreatic cancer; those diagnosed with diabetes aged >50yrs have an 8 times greater risk of developing pancreatic carcinoma in the following three years, compared to the general population*.

On examination, patients may appear cachectic, malnourished, and jaundiced. On palpation, an abdominal mass in the epigastric region may be felt, as well as an enlarged gallbladder (as per Courvoisier’s Law)

*Late onset diabetes in otherwise well patients should prompt further investigation

Courvoisier’s Law

Courvoisier’s law states that in the presence of jaundice and an enlarged/palpable gallbladder, malignancy of the biliary tree or pancreas should be strongly suspected, as the cause is unlikely to be gallstones.

This sign may be present if the obstructing tumour is distal to the cystic duct. In reality an enlarged gallbladder is present in less than 25% of patients with pancreatic cancer.

Differential Diagnosis

Pancreatic cancer often presents with vague and non-specific features, and as such the differential diagnoses are vast:

- Causes of obstructive jaundice – gallstone disease, cholangiocarcinoma

- Causes of epigastric abdominal pain – gallstone disease, peptic ulcer disease, gastric cancer, acute coronary syndrome

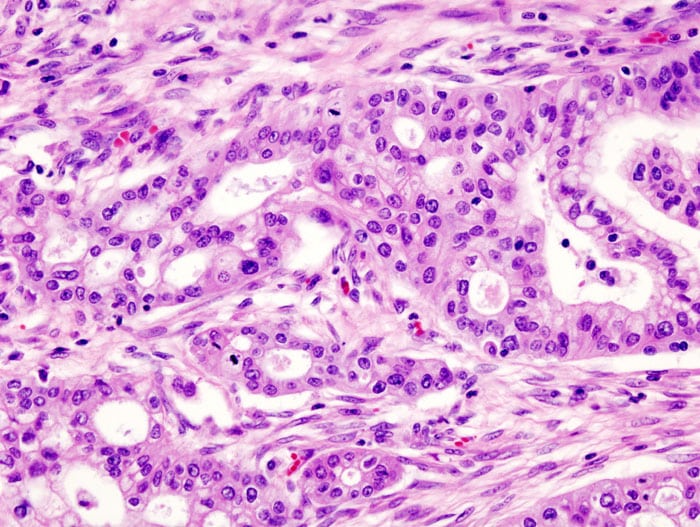

Figure 2 – Histology demonstrating pancreatic adenocarcinoma

Investigations

Laboratory tests

Any suspected pancreatic cancer should warrant initial blood tests, including FBC (anaemia or thrombocytopenia) and LFTs (raised bilirubin, alkaline phosphatase, and gamma-GT).

CA 19-9 is a tumour marker with a high sensitivity for pancreatic cancer and is useful in prognostication and in assessing response to treatment. It is unhelpful in initial diagnosis due to relatively poor specificity..

Imaging

Initial imaging for pancreatic cancer often starts with an abdominal ultrasound, which may demonstrate a pancreatic mass or a dilated biliary tree (or even hepatic metastases and ascites if late stage disease). However, ultrasound imaging has relatively poor sensitivity for detecting pancreatic cancer.

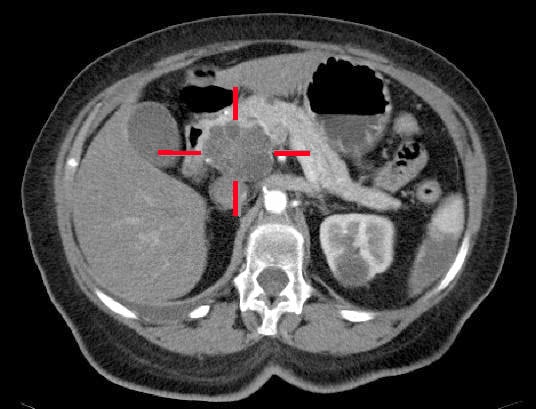

CT imaging with intravenous contrast (via pancreatic protocol, Fig. 3) is the gold standard for the preliminary diagnosis of pancreatic cancer. It can also provide prognostic informative, as it can stage disease progression. A CT chest-abdomen-pelvis scan will be further required once pancreatic cancer has been diagnosed for disease staging.

Endoscopic Ultrasound (EUS) is now largely used in the staging of adenocarcinoma, alongside potential tissue biopsy for histological confirmation (Fig. 2) where there is diagnostic uncertainty. Whilst tissue diagnosis is required for commencement of chemotherapy, in most operable cases, surgical procedures are performed prior to tissue diagnosis being obtained.

Current guidelines suggest PET-CT imaging in the full staging of pancreatic cancer for all patients, although its utility in diagnosis is debated. MRCP can also be useful to assess small lesions.

Figure 3 – A adenocarcinoma located in the pancreatic head, identified on CT scan

Management

The only curative management option for pancreatic adenocarcinoma is currently radical resection, however unfortunately at diagnosis, <20% of patients have a resectable tumour. Surgery is usually combined with chemotherapy either before surgery (neoadjuvant) or after surgery (adjuvant), with most patients receiving a FOLFIRINOX regime

Pancreatic tumours are classified as resectable, borderline resectable, or locally advanced, depending on the degree of contact between the tumour and surrounding vessels (namely the portal vein, superior mesenteric artery or vein, coeliac trunk, and common hepatic artery), and then metastatic disease.

Resectable and borderline may have surgery as a first option followed by adjuvant chemotherapy, although increasing evidence points to benefit for neoadjuvant chemotherapy in borderline resectable disease.

Surgery

The procedure performed is dependent mainly on the location of the tumour (typically as open procedures):

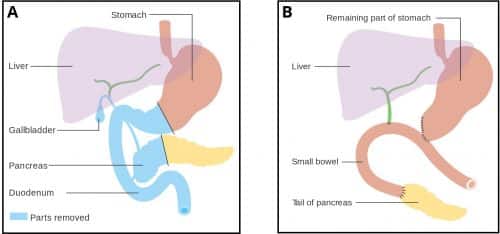

- Head of the pancreas lesions typically undergo a pancreaticoduodenectomy (termed a Whipple’s procedure) with regional lymphadenectomy

- Body or tail of pancreas typically undergo a distal pancreatectomy and splenectomy with regional lymphadenectomy

There is a high morbidity associated with these procedures; specific complications include formation of a pancreatic fistula, delayed gastric emptying, and pancreatic insufficiency.

All surgical patients should receive adjuvant chemotherapy, with patient fitness typically defining the regime chosen.

Whipple’s Procedure

A Whipple’s procedure involves the removal of the head of the pancreas, the antrum of the stomach, the 1st and 2nd parts of the duodenum, the common bile duct, and the gallbladder.

All viscera removed in the operation are done so due to their common arterial supply (the gastroduodenal artery), shared by the head of the pancreas and the duodenum.

Following this, the tail of the pancreas and the hepatic duct are attached to the jejunum, allowing bile and pancreatic juices to drain into the gut, whilst the stomach is subsequently anastomosed with the jejunum allowing for the passage of food.

Non-Resectable Disease

Patients with locally advanced disease (i.e. direct contact / invasion of local vessels) should undergo chemotherapy with re-staging being done to assess response. A small number of patients have significant response to chemotherapy and their disease becomes resectable.

In those with metastatic disease, palliative chemotherapy remains the mainstay of treatment; regimes used are dependent of performance status of the patient, either FOLFIRINOX regime for those with a good performance status, or gemcitabine therapy for those who may not tolerate the FOLFIRINOX. Those with a poor performance status should be considered for symptomatic management only.

In both locally advanced and metastatic disease, biliary and gastric outlet obstruction can be managed either with stents or surgical bypass procedures. Any exocrine insufficiency can lead to malabsorption and steatorrhoea, which can be managed with oral enzyme replacements.

Prognosis

Pancreatic cancer has a high metastatic capacity, even in small tumours, and metastasis is common at the time of diagnosis.. The prognosis in pancreatic cancer remains very poor, with overall 5-year survival rate around 10%.

In those receiving surgery, 5-year survival is around 20%, whilst in those with unresectable disease, median survival is 11 months with FOLFIRINOX chemotherapy.

Key Points

- Pancreatic cancer will often present with a combination of obstructive jaundice, abdominal pain, or weight loss

- Most cases are initially detected on CT scan, CA19-9 is a tumour marker used for monitoring disease progression

- Definitive management is surgical resection, often with adjuvant chemotherapy

- Pancreatic cancer has a 5-year survival rate of around 10%

Endocrine Tumours of the Pancreas

Endocrine tumours of the pancreas are those that arise from the endocrine cells of the pancreas. These are classified either functional or non-functional tumours, based on their hormone secretion status.

Functional tumours actively secrete hormones and their signs and symptoms are related to this, whilst non-functional tumours do not secrete active hormones and clinical features are related purely to their malignant spread.

Endocrine tumours of the pancreas may be associated with multiple endocrine neoplasia 1 syndrome (MEN1)* although they often arise spontaneously in the absence of of other tumours or syndromes.

*MEN1 typically consists of hyperparathyroidism, endocrine pancreatic tumours, and pituitary tumours (typically prolactinomas)

Clinical Features

| Cell Type | Secreted Hormone (name of tumour) | Normal Physiological Function | Features of Functional Tumour |

| G cells | Gastrin (gastrinoma) |

Stimulates the release of gastric acid | Zollinger-Ellison syndrome, resulting in severe peptic ulcers, refractory to medical treatment, with diarrhoea and steatorrhoea |

| α Cells | Glucagon (glucagonoma) |

Increase blood glucose concentration | Hyperglycaemia, diabetes mellitus, and necrolytic migratory erythema |

| β Cells | Insulin (insulinoma) |

Decrease blood glucose concentration | Symptomatic hypoglycaemia, such as sweating or changed mental state, improving with consumption of carbohydrates |

| δ Cells | Somatostatin (Somatostatinoma) |

Inhibits the release of GH, TSH and prolactin from the anterior pituitary, and of gastrin | Diabetes mellitus, steatorrhoea, gallstones (due to inhibition of cholecystokinin), weight loss, and achlorhydria (due to gastrin inhibition) |

| Non-islet cells | Vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIPoma) |

Secretion of water and electrolytes into the gut. Relaxation of enteric smooth muscle. | Prolonged profuse watery diarrhoea, severe hypokalaemia, and dehydration (also known as Verner-Morrison syndrome) |

Table 1 – Endocrine tumours of the pancreas

Investigation and Management

All cases should be discussed at a multi-disciplinary team meeting where management can be guided. Certain blood tests can be used to identify the specific subtype, based on the hormone secreted (Table 1)

Pancreatic NETs are best investigated with a combination of CT imaging, MRI imaging, and EUS along with a DOTATATE-PET scan. Small non-functional well differentiated pancreatic NETs (<1cm) can simply be observed, whilst larger or functioning tumours need resection, with any distant metastatic disease also resected if the tumour is low grade and the metastases is low volume.

Somatostatin analogues can be used to control and ameliorate the effects of hormonal hypersecretion (even in the case of somatostatinomas).