Introduction

Oesophageal tears are ruptures to any part of the oesophageal wall. Although rare, complete ruptures have a mortality of between 50 – 80%, so early recognition and treatment is essential.

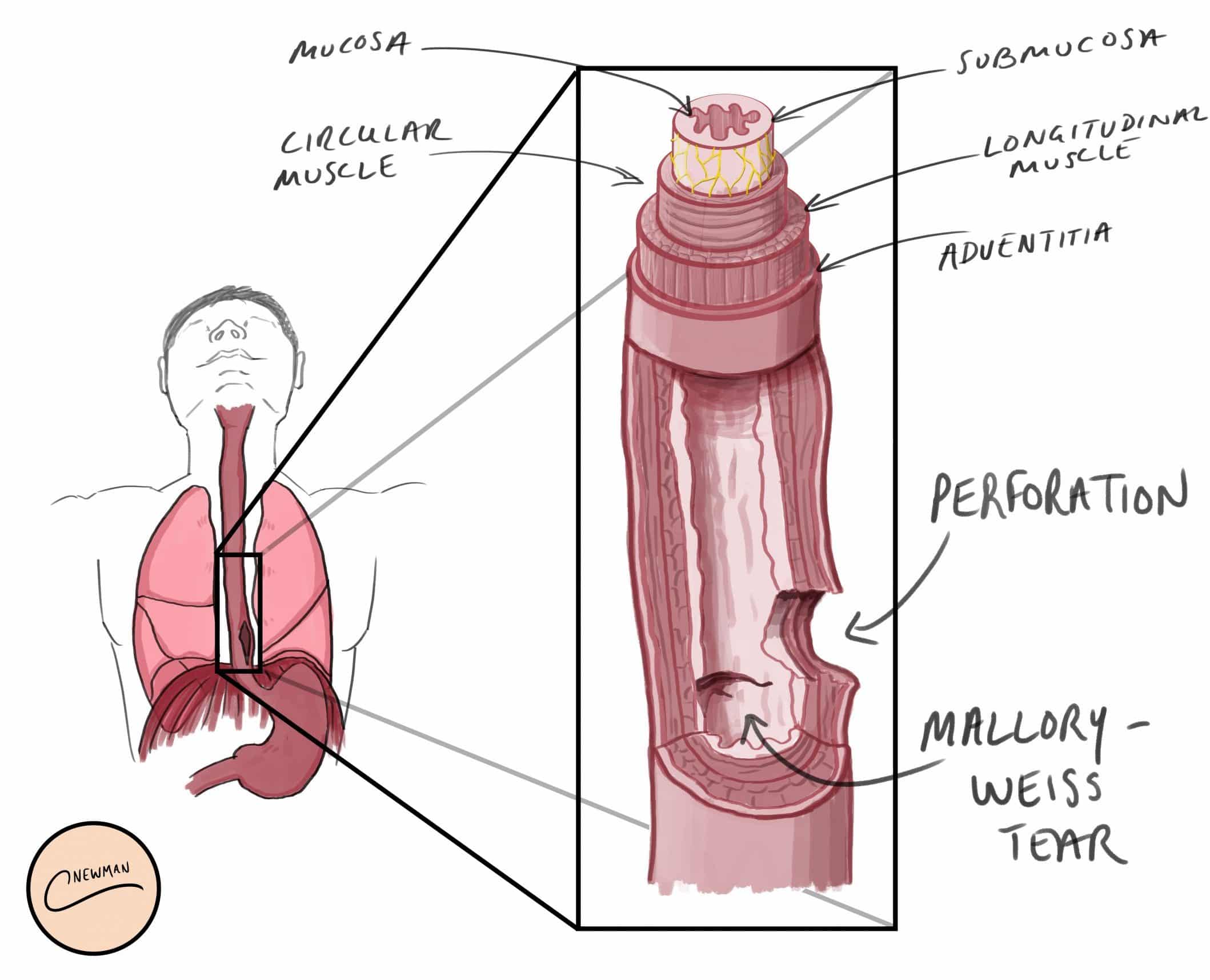

There is a wide spectrum in the severity of oesophageal tears, the main two subcategories being superficial mucosal tears (Mallory-Weiss tears) and full thickness ruptures (Boerhaave’s syndrome)

Oesophageal Perforation

Oesophageal perforation is a full thickness rupture of the oesophageal wall; if it is spontaneous (often due to vomiting), it is often called Boerhaave’s syndrome.

Perforation will result in leakage of stomach contents into the mediastinum and pleural cavity, which can result in severe sepsis, resulting in physiological collapse, multi-organ failure, and death. Rapid identification and management of this surgical emergency is therefore essential.

Aetiology

The two most common causes are iatrogenic (e.g. endoscopy) or after severe forceful vomiting (Boerhaave’s syndrome).

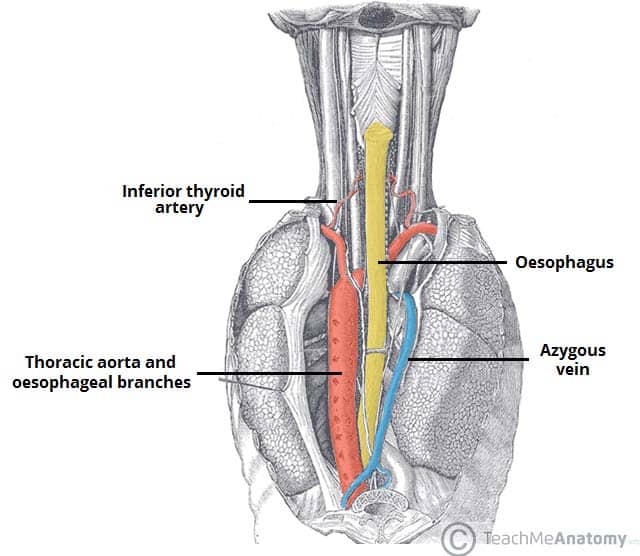

The most common site of perforation is just above the diaphragm in the left postero-lateral position, 2-3cm proximal to the gastro-oesophageal junction, although can occur at any location in the oesophagus.

They are rare, with an incidence of 3 cases per million per year. Indeed, most cases occur in patients with an otherwise normal oesophagus.

Clinical Features

The classical picture for oesophageal perforation is of a patient who presents with severe sudden-onset retrosternal chest pain, respiratory distress, and subcutaneous emphysema following severe vomiting or retching.

However, subcutaneous emphysema is frequently absent and the full combination of vomiting, chest pain and subcutaneous emphysema (Mackler’s triad) is only seen in around 15% of patients.

On examination, patients will often present critically unwell, with features of severe sepsis. Due to the perforation occurring intra-thoracic, clinical abdominal signs may be absent. On chest examination, dullness to percussion and reduced air entry will likely be present in the presence of pleural effusion.

Investigation

Urgent blood tests, including a full blood count, C-reactive protein, and Group and Screen, must be taken for all those with a suspected oesophageal perforation. Initial imaging via a chest radiograph (CXR) may demonstrate evidence of pneumomediastinum or intra-thoracic air-fluid levels (however do not delay definitive imaging while awaiting the CXR)

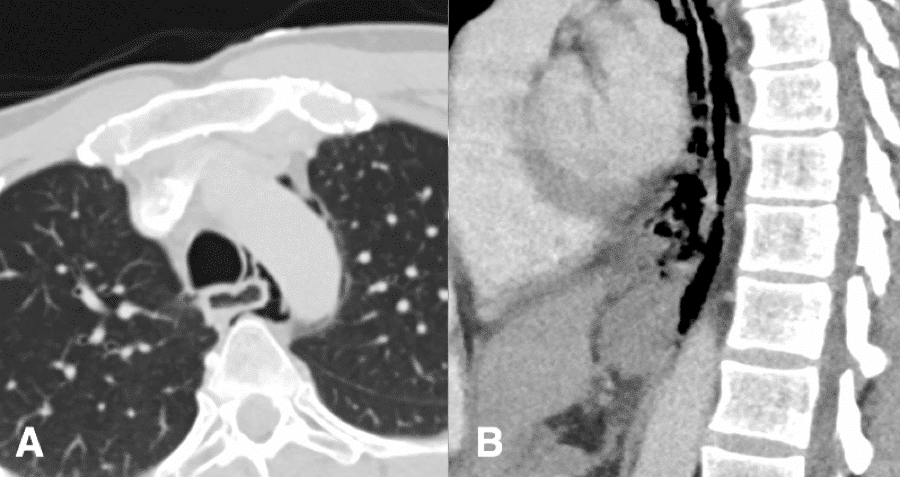

The investigation of choice is an urgent CT chest-abdomen-pelvis scan with intravenous and oral contrast (Fig. 2). This may show air or fluid in the mediastinum or pleural cavity; leakage of oral contrast from the oesophagus into the mediastinum or chest is pathognomonic. Water-soluble contrast should be used if possible to prevent worsening of inflammation due to leakage into the thoracic cavity.

If there is a high level of clinical suspicion (based on the history and examination) but with equivocal imaging findings, the patient should have an urgent endoscopy in theatre.

Figure 2 – CT chest-abdomen imaging showing Boerhaave (A) axial image showing extraluminal air surrounding the trachea and oesophagus (B) sagittal image showing discontinuity in the posterolateral distal oesophageal wall

Management

These patients are often septic and haemodynamically unstable. Urgent and aggressive resuscitation is therefore essential. Ensure high flow oxygen and fluid resuscitation, and broad-spectrum antibiotics and anti-fungals are given immediately.

Management of these patients require involvement of multiple teams, including upper GI surgery, radiology, microbiology, intensive care, endoscopy and dieticians.

Definitive management varies depending on whether the perforation was spontaneous or iatrogenic, the location of the perforation, resources/expertise available, as well as the performance status, co-morbidities, and pre-existing oesophageal disease. The principles of definitive management (both operative and non-operative) following initial resuscitation involves:

- Control of the oesophageal leak, accounting for any distal obstruction

- Eradication of mediastinal and pleural contamination

- Decompress the oesophagus (typically via a trans-gastric drain or endoscopically-placed NG tube)

- Nutritional support

Surgical Management

Drainage of intrathoracic contamination is often needed via insertion of large bore surgical chest drains (ideally under sedation), either in A&E or in theatre (whichever is more feasible, without delaying treatment)

Most patientswith a spontaneous perforation will need immediate surgery to control the leak and wash out of the chest. This is almost always via a thoracotomy +/- laparotomy depending on site of perforation. Patients also need an on-table endoscopy to determine the site of perforation, assess for the presence of a distal obstruction, and help gauge the planned site of the incision.

Surgical options include primary repair, resection, diversion/exteriorisation via oesophagostomy, or simply washout and placement of drains.

Leakage is common and patients should therefore have a repeat CT scan with oral contrast at 10-14 days before starting oral intake. They may warrant a feeding jejunostomy to be inserted at the time of initial surgery for nutritional optimisation.

Non-Operative Management

Patients with iatrogenic perforations are often more stable than those with spontaneous perforations* and may be suitable for non-operative management.

Other patients potentially suitable for non-operative management include those with minimal contamination, a contained perforation, or no symptoms or signs of mediastinitis. Patients with spontaneous perforations who are too frail or with extensive co-morbidities to undergo surgery may also be candidates for non-operative treatment

*This is because the patient will usually have been NBM before the procedure and therefore there is not the forceful vomiting associated with spontaneous perforations and does not have the associated contamination

Non-operative treatment involves:

- Urgent resuscitation and transfer to a Intensive Care or High Dependency Unit

- Appropriate antibiotic and anti-fungal cover

- Endoscopic therapy may be appropriate if available – this includes clips, covered stents, endoscopic suturing, or endoscopic vacuum therapy

- Kept nil-by-mouth for 1-2 weeks, with endoscopic insertion of an nasogastic tube placed on drainage

- Large-bore chest drain insertion, either as a surgical or ultrasound-guided technique

- Total Parenteral Nutrition (TPN) or feeding jejunostomy insertion

Prognosis

Morbidity and mortality are high (between 50–80%) and therefore early identification and treatment is essential to ensure optimal outcomes.

Mallory-Weiss Tears

Mallory-Weiss tears are lacerations in the oesophageal mucosa, usually at the gastro-oesophageal junction.

They tends to occur after a period of profuse vomiting, and in turn resulting in a short period of haematemesis. They account for approximately 5% of all cases of haematemesis.

They are generally small and self-limiting, in the absence of clotting abnormalities or anti-coagulation drugs. Presentation with haemorrhagic shock is possible but rare.

Investigation and Management

The investigation and management of Mallory-Weiss tears is the same as for any other upper GI bleed (as discussed here).

Most cases can be managed conservatively, rarely warranting interventional or surgical management.

Key Points

- Oesophageal full-thickness rupture is a surgical emergency and rapid identification and management is essential, with liaison with an upper GI surgery service

- The initial investigation of choice for any suspected rupture is a CT Chest-Abdomen-Pelvis scan with intravenous and oral contrast

- Many factors will influence whether the patient will require surgical or non-operative management, which includes endoscopic management

- Mallory-Weiss tears are lacerations in the oesophageal mucosa, however they are generally small and self-limiting