This article is for educational purposes only. It should not be used as a template for consenting patients. The person obtaining consent should have clear knowledge of the procedure and the potential risks and complications. Always refer to your local or national guidelines, and the applicable and appropriate law in your jurisdiction governing patient consent.

Overview of Procedure

A fistula-in-ano typically results from presence of a previous peri-anal abscess, however, other causes such as inflammatory bowel disease (Ulcerative Colitis or Crohn’s Disease), trauma, or radiation changes should be considered. A digital rectal examination and proctoscopy should also be performed to assess the integrity of the bowel mucosa for signs of inflammatory bowel disease or any evidence of internal fistula openings.

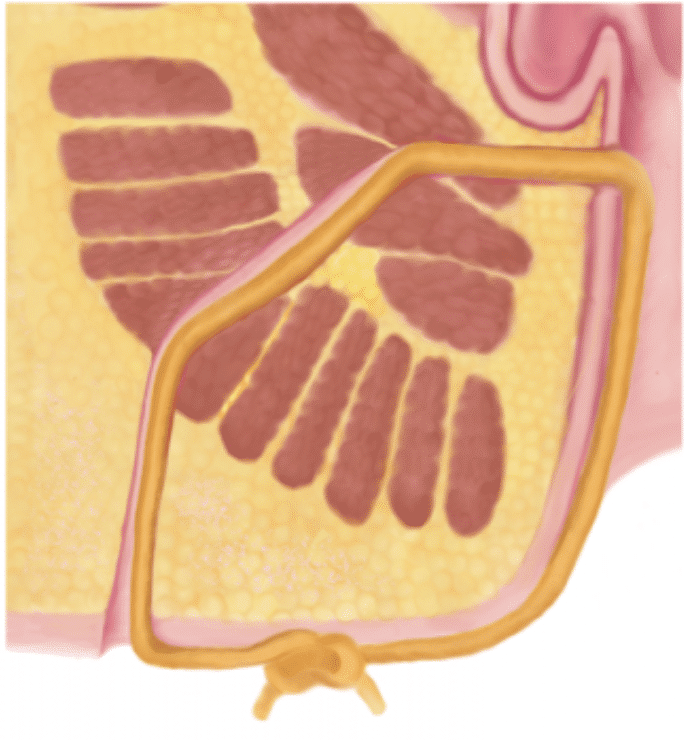

A seton can be placed when the fistula tract is probed and the tract is higher in the sphincter mechanism (Fig. 2), with the seton passes through the tract. It is then loosely tied in place and repeat procedures are likely needed. Laying open of a fistula (fistulotomy) occurs where a fistula probe is passed through the tract and the overlying tissues are divided with a knife or diathermy, if they are superficial and do not involve the sphincter complex.

Figure 1 – An illustration of a seton in-situ for a perianal fistula

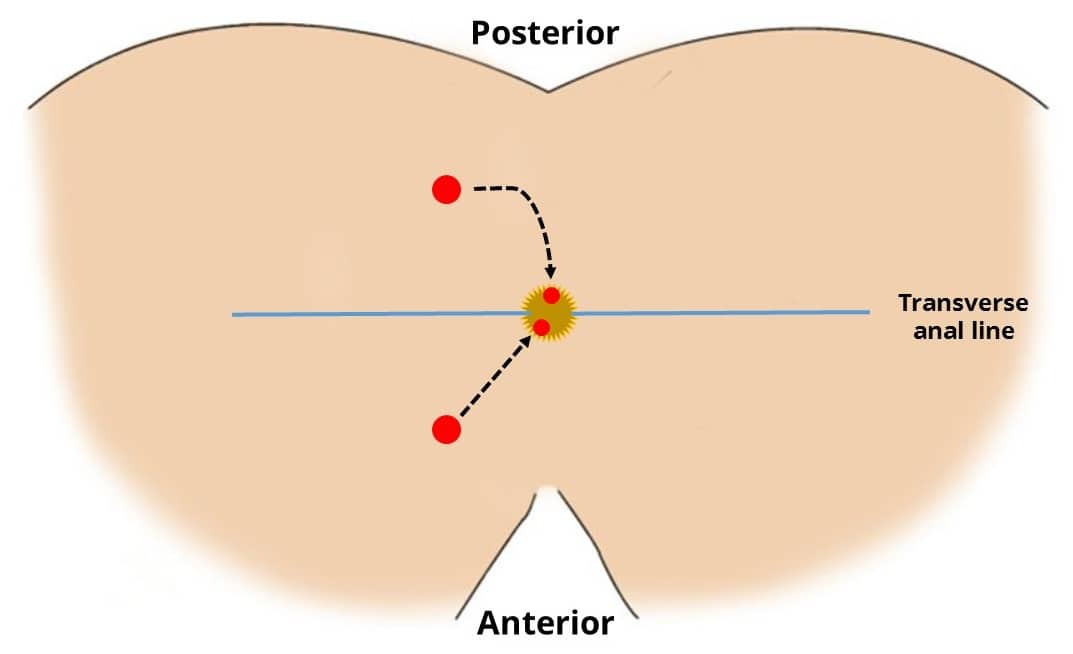

The Goodsall Rule

The Goodsall rule (Fig. 1) can be used clinically to predict the trajectory of a fistula tract, depending on the location of the external opening:

- External opening posterior to the transverse anal line – fistula tract will follow a curved course to the posterior midline

- External opening anterior to the transverse anal line – fistula tract will follow a straight radial course to the dentate line

Complications

Intra-Operative

| Complication | Description of Complication | Potential Ways to Reduce Risk |

| Bleeding | Typically there is only minimal blood loss | Gentle probing of the fistula tracts; only lay open superficial tracts to avoid deeper structures |

| Damage to the anal sphincter complex | Typically perform a circum-anal incisions to avoid the risk of sphincter damage | |

| Anaesthetic risks | Includes damage to the teeth, throat and larynx, reaction to medications, nausea and vomiting, cardiovascular and respiratory complications | Forms a part of the anaesthetist assessment before the operation |

Early

| Complication | Description of Complication | Potential Ways to Reduce Risk |

| Pain | Pudendal nerve block with local anaesthesia can help with post-operative pain | |

| Bleeding | There is a small chance of bleeding and bruising post-operatively | |

| Infection | Superficial wound infection or small abscess formation can occur within the fistula tracts | |

| Scarring | Any incision will result in a scar, which may form a keloid scar, particularly in high risk ethnicities | |

| Blood clots | DVTs and PEs are a possibility in any operation, however are low risk as the duration of the procedure is short | The patient will be given anti-embolism stockings and low molecular weight heparin peri-operatively to minimise this risk as deemed appropriate. |

Late

| Complication | Description of Complication | Potential Ways to Reduce Risk |

| Recurrence | Fistula disease has high rates of recurrence, even following extensive surgery | Ensure any underlying disease pathology, e.g. Crohn’s disease, are concurrently treated |

| Anal stenosis | Healing of the fistula tract or scarring from multiple wounds can lead to fibrosis of the anal canal | |

| Delayed wound healing | Usually healing should occur within 12 weeks unless there is underlying pathology e.g. Crohn’s disease |