Introduction

Tonsillitis refers to inflammation of the palatine tonsils, most commonly due to infection.

Whilst most cases of tonsillitis are mild and fully resolve, significant complications include deep neck space infection and airway compromise.

Tonsillitis is a common presentation in primary care, most common in children and young adults. Recurrent tonsillitis has an incidence in the UK of around 100 per 1000 population a year.

In this article, we shall look at the pathophysiology, clinical features and management of tonsillitis.

Pathophysiology

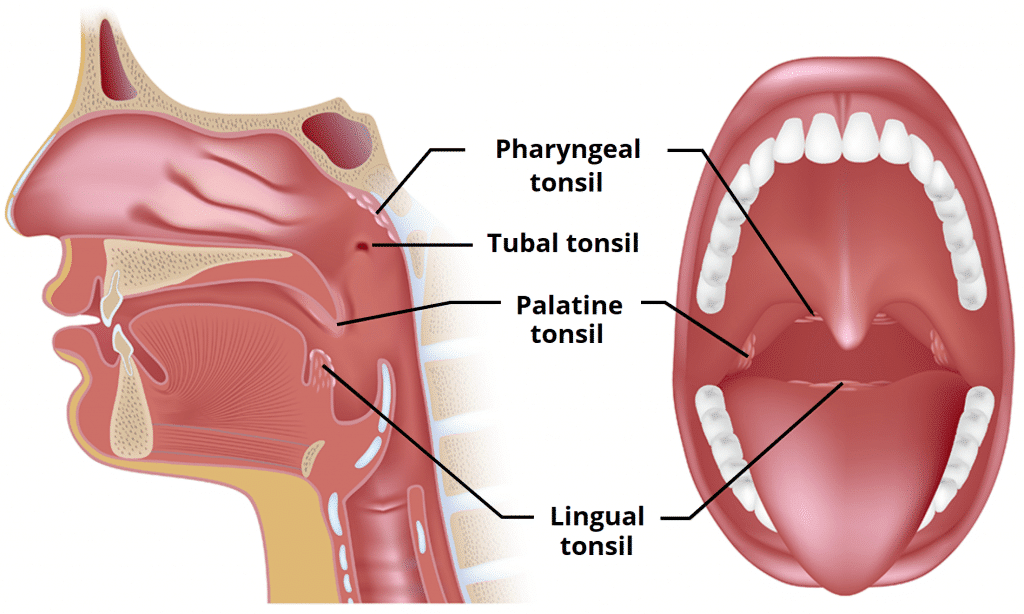

The palatine tonsils are located within the oropharynx as part of Waldeyer’s ring (Fig. 1). Waldeyer’s ring is a collection of lymphatic tissue located within the pharynx, forming a ringed arrangement, comprised of the pharyngeal tonsil, tubal tonsils (x2), palatine tonsils (x2), and lingual tonsil.

Tonsillitis is most commonly caused by viral infections (50-80% of cases), including adenovirus, rhinovirus, influenza, and parainfluenza. Bacterial causes account for approximately one third of cases (causative organisms include S. Pyogenes, S. Aureus, and M. Catarrhalis).

Clinical Features

Tonsillitis presents with odynophagia or dysphagia, often with associated pyrexia or halitosis. A cough or coryzal symptoms may also be present.

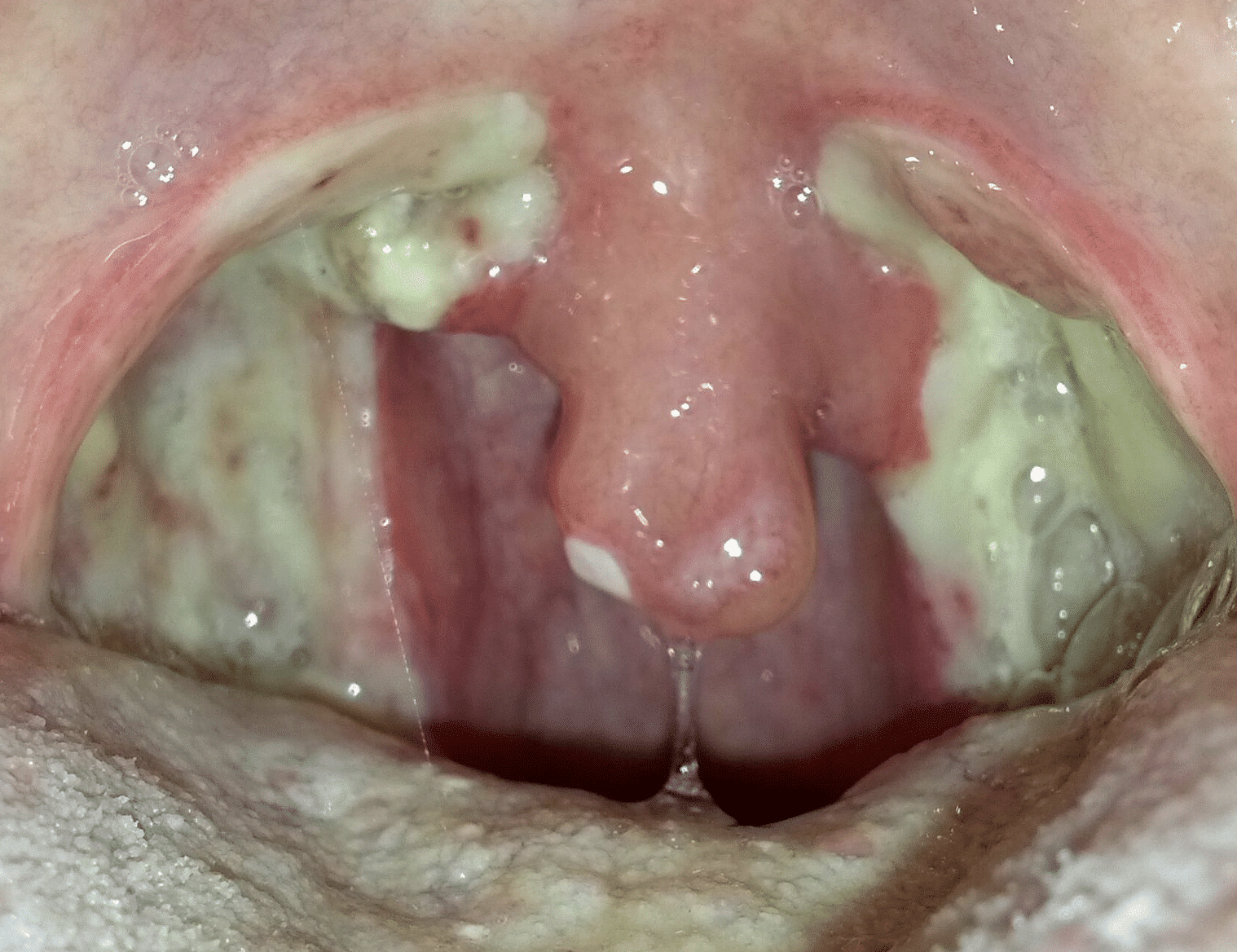

On examination, the tonsils will appear erythematous and swollen (Fig. 2). A purulent exudate may be present (more common in bacterial cases), as well as anterior cervical lymphadenopathy.

Figure 2 – Patient with tonsillitis, with the tonsils appearing erythematous & swollen

The Centor Criteria

The Centor criteria are often used in primary care to assess for the likelihood of bacterial infection in tonsillitis

Antibiotics should be considered if ≥2 criteria are met:

- History of pyrexia

- Tonsillar exudates

- No cough

- Tender anterior cervical lymphadenopathy

The Centor criteria however is not suitable for emergency presentations and is rarely used in a hospital setting.

Differential Diagnosis

Important differentials to consider include head and neck malignancy, haematological malignancies, or deep space neck abscess.

Investigation

Tonsillitis is often a clinical diagnosis; further investigations are only warranted in cases with suspected complications (see below).

For those warranting potential hospital admission, patients should have routine bloods (including FBC, U&Es, CRPs, LFTs, and clotting) performed. Those

Consider a CT neck scan with intravenous contrast if a deep neck space infection is suspected

Management

Ensuring sufficient analgesia (normally achieved with Difflam spray and regular paracetamol ±NSAIDs) and hydration is the mainstay of treatment.

Hospital admission may be required in uncomplicated cases who cannot swallow fluids after initial management. If the cause is thought to be bacterial, antibiotics should be prescribed* (typically penicillin-based, however follow local guidelines)

*Remember that starting amoxicillin in tonsillitis caused by EBV can result in a maculopapular rash developing

Tonsillectomy

The definitive prevention for patients with recurrent tonsillitis is with tonsillectomy. Typical indications for surgical excision of the tonsils include:

- ≥7 episodes in the preceding year, or ≥5 episodes in each of preceding 2 years, or ≥3 episodes in each of preceding 3 years

- Suspected malignancy

- Presence of sleep apnoea

- Two previous peritonsillar abscesses

The main complication from tonsillectomy is secondary bleeding (>24hrs post-op) from infection to the tonsillar bed site, occurring in around 5% of cases and most at post-operative days 5-9. This is often treated conservatively, with antibiotic and hydrogen peroxide mouth wash; approximately 1% of patients will require surgical intervention for arrest of secondary haemorrhage.

Complications

Peritonsillar Abscess

A quinsy is a peritonsillar abscess, a rare complication of bacterial tonsillitis. Patients present with a severe sore throat (worse unilaterally), with associated severe odynophagia. Associated symptoms include stertor and trismus; in children, they can present in similar ways.

On examination (often difficult due to trismus), there will be extensive erythema and soft palate swelling, with the anterior arch being pushed medially and a deviated uvula (Fig. 5).

Patients should be admitted and started on intravenous antibiotics, with regular analgesia and topical analgesic throat sprays. All peritonsillar abscess will require either needle aspiration (following topical local anaesthetic) or an incision and drainage (with further opening via use of Tilley’s forceps)

Figure 5 – A quinsy, causing significant uvula deviation

Key Points

- Tonsillitis refers to inflammation of the palatine tonsils, most cases of which will resolve with conservative management

- The Centor criteria is often used in primary care to assess for the likelihood of bacterial infection

- Peritonsillar abscess and deep space neck infections are rare complications of tonsillitis that should be assessed for in any prolonged, severe, or atypical case