Introduction

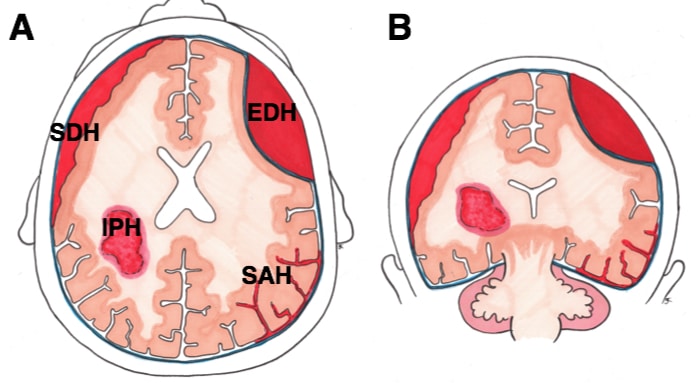

Intracranial haemorrhage can be classified as intra-axial (within the brain parenchyma) or extra-axial (outside the brain). An extradural haematoma (also termed an epidural haematoma) is an extra-axial bleed occurring between the dura and skull bone.

Around 2% of all head injuries presenting to the emergency department are extradural haematomas (EDHs), with associated significant morbidity and mortality, especially with advancing age.

The incidence of EDHs is higher in men, with the most common age group affected being the 2nd to 3rd decades (likely associated to high-risk behaviours, including crime/violent activities and participate in contact sports).

In this article, we will be discussing the aetiology, presentation and management of patients presenting with extradural haematoma.

Pathophysiology

Extradural haematomas typically occur following blunt force head trauma resulting in a linear skull fracture, with no or minimal displacement. Parieto-temporal fractures are most commonly implicated (73.5%), typically secondary to events such as road traffic collisions (in 57%), assault (in 22%) and falls (in 9%).

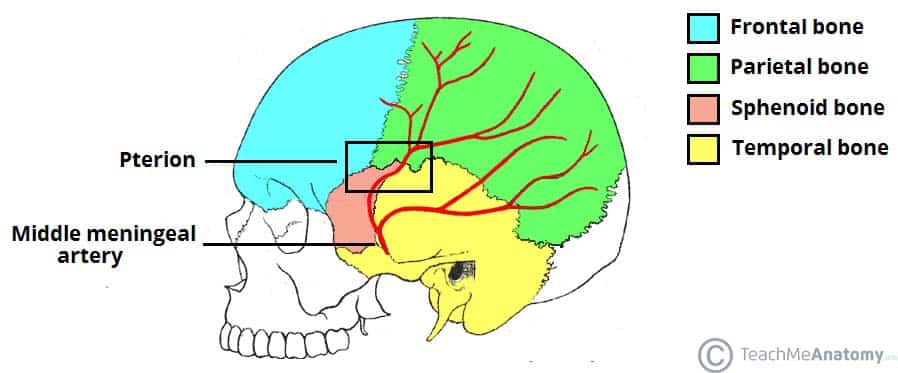

The middle meningeal artery is the most common source of bleeding (around 85%), occurring due to a fracture at the pterion, lacerating the anterior branch of this vessel as it runs beneath (Fig. 2). Diploic vein bleeds, vascular malformations, or infective pathology are less common causes of EDH.

Figure 2 – The path of the middle meningeal artery, in relation to the pterion

Clinical Features

Patients with a extradural haematoma will mostly present following a history of trauma or of a fall.

The classic picture is of an initial loss of consciousness at the time of injury, followed by a lucid period, before further deterioration (albeit this is present in only around 30% cases). Other symptoms may include headache, nausea or vomiting, or progressive drowsiness.

On examination, patients may have a low conscious level, localising neurological signs, or clinical features of brain herniation or raised intracranial pressure. If left untreated, this can progress to coma and death.

Investigations

All patients presenting with a suspected traumatic head injury should be investigated and managed as per ATLS guidelines.

For initial investigations, routine urgent bloods, including FBC, U&Es, CRP, clotting profile, and a group and save, should be taken.

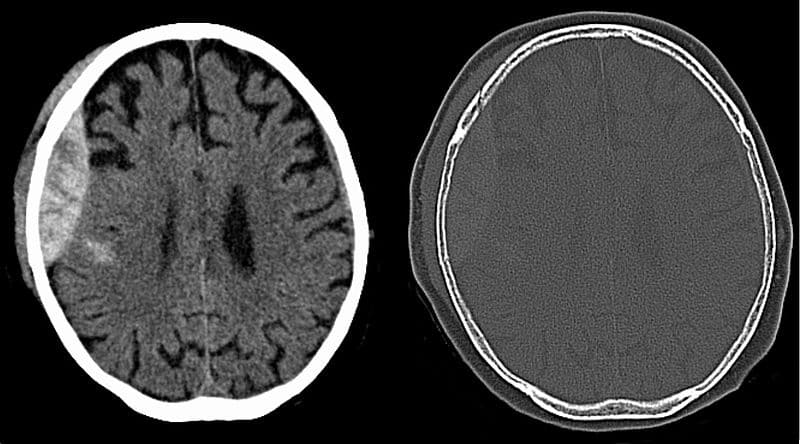

CT imaging of the head (Fig. 4) is required for any suspected of EDH. A EDH classically show as hyperdense biconvex* lesions, potentially with an associated skull fracture. Further imaging may be required thereafter for work-up.

*The distinguishing biconvex lens-shaped of EDH is due to the bleeding being limited by the firm attachments of the dura to the suture lines on the inner surface of the cranium

Management

As discussed, the majority of EDHs are traumatic in nature, therefore should be managed as per the ATLS protocol.

Once the patient has been stabilised and the EDH is confirmed, urgent neurosurgical opinion is required (if deemed suitable for surgical intervention).

Current management guidelines from the Brain Trauma Foundation suggest that not all EDHs require surgery:

- > 30cm3 should be managed surgically regardless of other factors

- <30cm3 with low thickness, minimal midline shift and GCS >8 without any focal neurological deficits are candidates for conservative management

Conservative management typically involves serial CT imaging and close neurological observation.

Whilst no specific surgical procedure shows definitive benefit, craniotomy may be preferred in certain circumstances versus Burr holes in others.

Any bleeding source identified and localised should be controlled through ligation or cauterisation, if necessary.

Post-operatively, patients should be observed on either a neuro-critical care or high dependency unit with close neuro-observations and routine post-operative CT scans to ensure adequate clot removal. Ongoing neurorehabilitation is often required.

Prognosis

Overall mortality rate is around 30%. Risk factors for poor prognosis include increasing age, temporal location, low GCS at presentation, and evidence of herniation or raised intra-cranial pressure.

Key Points

- Extradural haematomas are typically traumatic and arterial, occurring most commonly in younger men

- Classic presentation is of a lucid interval then rapid progression to signs of raised ICP and herniation without intervention.

- CT imaging will show an area of hyperdensity that is convex and does not cross the suture lines.

- Management – extradural haematomas can be managed conservatively or surgically depending on a number of factors including size, midline shift, and GCS.