The shoulder is a highly mobile joint that sacrifices stability for an increased range of movement. As a consequence of this trade off, dislocations are common, with an incidence of up to 1.7% in the general population.

Shoulder dislocations account for over half of major joint dislocations which present to emergency departments; if not managed correctly they can lead to chronic joint instability and chronic pain.

Aetiology

The most common type of dislocation is anteroinferior (usually just termed ‘anterior’), constituting around 95% of shoulder dislocations, with posterior and inferior dislocations making up the remainder.

- An anterior dislocation is classically caused by force being applied to an extended, abducted, and externally rotated humerus

- A posterior dislocation* is typically caused by seizures or electrocution, but can occur through trauma (a direct blow to the anterior shoulder or force through a flexed adducted arm)

*Importantly, posterior dislocations are the most commonly missed dislocation of the shoulder, especially as the radiographic evidence of them can often be subtle

Clinical Features

All dislocations present with a painful shoulder, acutely reduced mobility, and a feeling of instability. Patients will be reluctant to move the affected limb.

On examination, there is often an asymmetry with the contralateral side. Often there is a loss of shoulder contours (from a ‘flattened deltoid’) and an anterior bulge from the head of the humerus may also be seen.

It is important to assess the neurovascular status of the arm, which can become compromised in some cases, especially the axillary and suprascapular nerves.

Associated Injuries

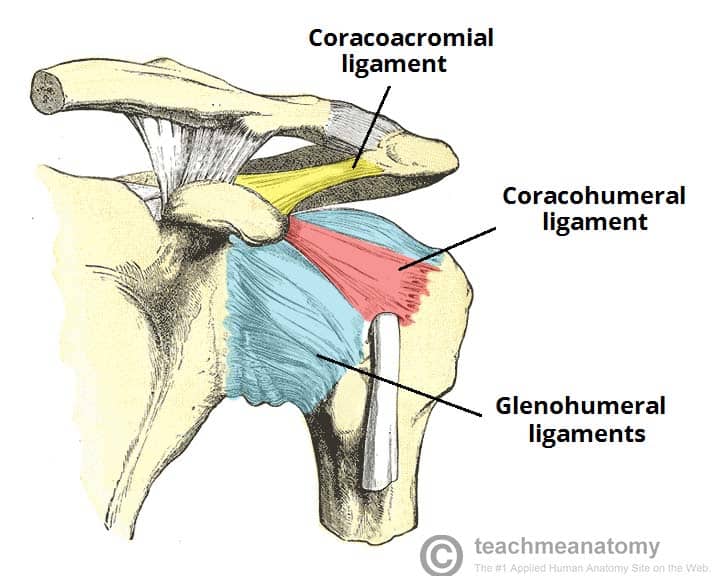

Shoulder dislocations have many commonly associated injuries, which can be divided into bony or labral and ligamentous problems:

- Bony:

- Bony Bankart lesions are fractures of the anterior inferior glenoid bone, most commonly present in those with recurrent dislocations

- Hill-Sachs defects are impaction injuries to the chondral surface of the posterior and superior portions of the humeral head, present in approximately 80% of traumatic dislocations

- Fractures of the greater tuberosity and the surgical neck of humerus can also occur

- Labral, ligamentous, and rotator cuff:

- (Soft) Bankart lesions are avulsions of the anterior labrum and inferior glenohumeral ligament

- Glenohumeral ligament avulsion

- Rotator cuff injuries occur frequently in anterior dislocations; in younger patients, around a third have at least one tear

Investigations

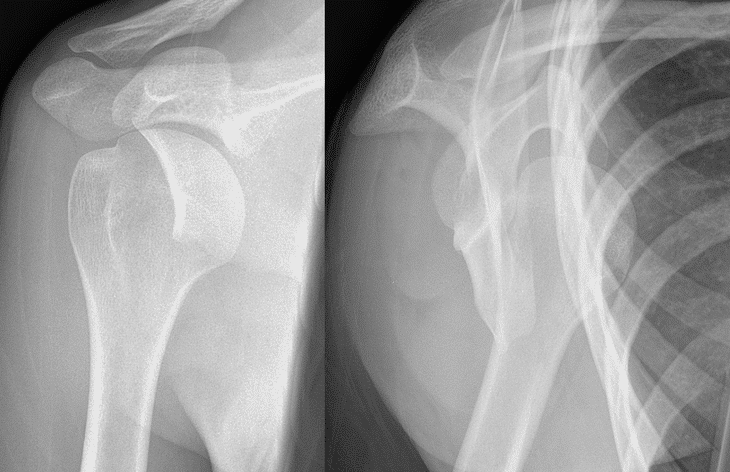

Imaging forms the bulk of investigations required for shoulder dislocations. Plain radiographs are usually adequate in the acute setting; a trauma shoulder series is required, with at least 2 views performed, comprising anterior-posterior, Y-scapular, and/or axial views

Anterior dislocations can usually be spotted on the anterior-posterior film as the humeral head is visibly out of glenoid fossa, and the Y-scapular view also can confirm this. It is important to remember to check for concurrent bony injuries too.

Figure 2 – Anterior shoulder dislocation, showing both AP and Y views

The ‘light bulb sign’ suggests posterior dislocation (Figure 3), as the humerus is fixed in internal rotation. The Y view is very useful for differentiating between anterior and posterior dislocations.

If labral or rotator cuff injuries are suspected, an MRI of the shoulder may also be warranted for further investigation and classification.

Management

Management should initially be an A to E trauma assessment of the patient, as dislocations frequently occur following trauma, ensuring to also stabilise and examine for other injuries. Provide appropriate analgesia, as this will aid in the management of the dislocation too.

As with most orthopaedic conditions, the principle is reduction, immobilisation and rehabilitation. For shoulder dislocations, a closed reduction, such as the Hippocratic method, should be performed by a trained specialist.

Ensure to assess the neurovascular status both pre- and post-reduction. A failed closed reduction may require manipulation under anaesthesia.

Figure 3 – Lightbulb Sign, suggesting a posterior shoulder dislocation

Once reduced, the arm should be placed in to a broad-arm sling; the length of immobilisation is debated for anterior dislocation, however is typically 2 weeks with early physiotherapy

All dislocations require physiotherapy aiming to restore range of movement, functionality and to strengthen the rotator cuff and pericapsular musculature. Future surgical treatment may be warranted for ongoing shoulder pain, recurrent dislocations, joint instability, large Hill-Sachs defects, or large (bony) Bankart lesions.

Prognosis

Despite treatment, chronic pain, limited mobility, stiffness, and recurrence are possible; unfortunately, recurrence is still relatively common, particularly in those who continue high risk activities.

Other common complications include adhesive capsulitis, nerve damage, and rotator cuff injury is common and may require surgery. Degenerative joint disease can occur, typically after labral and cartilaginous injuries and chronic recurrence.

Key Points

- The type of shoulder dislocation is classified in relation of the humeral head to the infraglenoid tubercle

- There are many associated injuries for all types of shoulder dislocation

- A trauma series of radiographs are required for evaluation and neurovascular status must be assessed, both pre- and post-reduction

- Treatment is primarily non-operative, following “reduce, restrict, rehabilitate” rules