Introduction

Degenerative disc disease refers to the natural deterioration of the intervertebral disc structure, such that they become progressively weak and begin to collapse.

While many patients remain asymptomatic, a proportion will develop pain and further complications.

Degenerative disc disease is often related to aging, further influenced by environmental and lifestyle factors (e.g. sedentary lifestyle, occupation, smoking), and increased body weight (especially in lumbar spine).

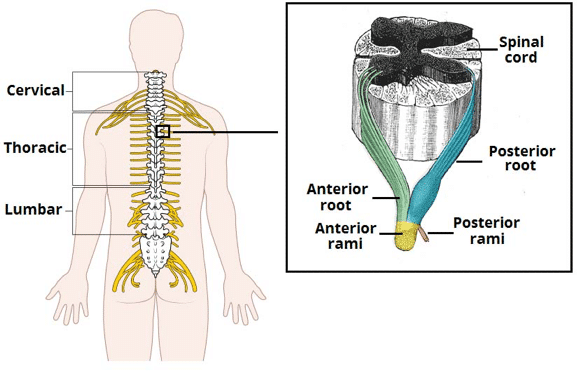

In this article, we mainly focus on lumbar disc disease, however degenerative disc disease can affect every level of the spine and presentation will vary based on this.

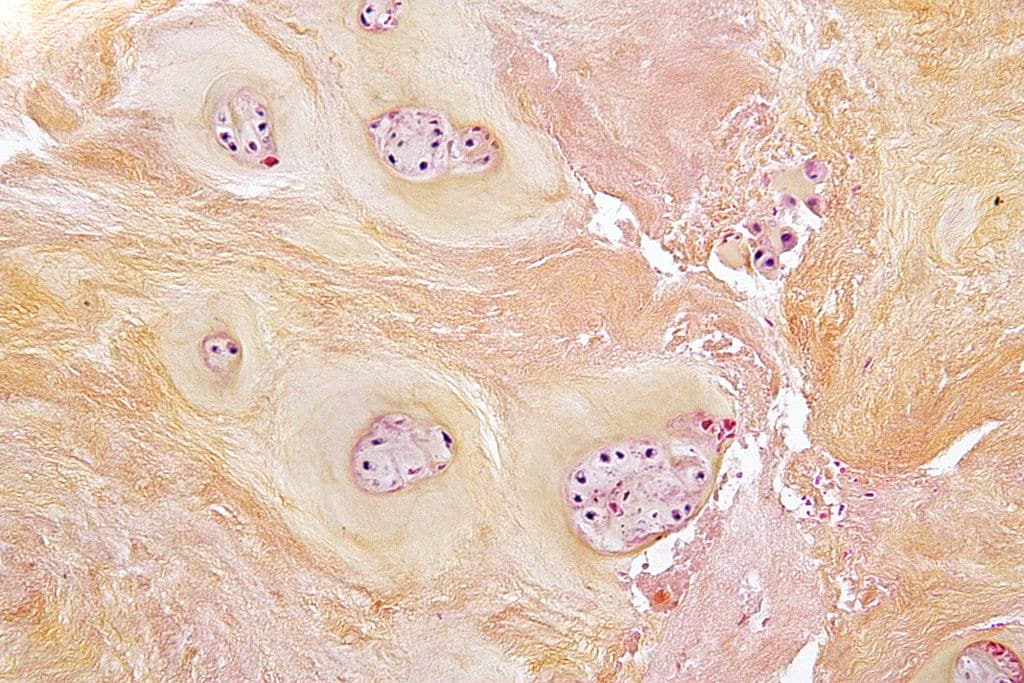

Figure 1 – The origin of the spinal nerves from the spinal cord

Pathophysiology

The cascade of changes seen degenerative disc disease can be divided into three parts, the duration of which can vary:

- Dysfunction – outer annular tears and separation of the endplate, cartilage destruction, and facet synovial reaction

- Instability – disc resorption and loss of disc space height, along with facet capsular laxity, can lead to subluxation and spondylolisthesis

- Restabilisation – degenerative changes lead to osteophyte formation and canal stenosis

As an approximate series of events, initially disc dehydration occurs (often through age-related reduced proteoglycan content) with annulus fibrosus tears, resulting in a herniation of the nucleus pulposus.

There then becomes disc fibrosis and resorption, with subsequent loss of disc space height and increased susceptibility to injury. Osteophytes can then form, which in turn can subsequently lead to spinal stenosis.

Clinical Features

The clinical features of degenerative disc disease depend on the region and severity of the disease. Importantly, many people with degenerative disc disease identified incidentally on imaging may not have symptoms.

Symptomatic patients will typically initially present with localised back pain. This may be due to mechanical stresses (e.g. muscle compensation for loss of spinal balance, or abnormal contact between bones) or as neuropathic pain (stenosis, spondylolisthesis, synovial cysts)

When the disc degeneration progresses* (either from instability, stenosis or osteophyte compression), the pain can become more severe and further become radicular pain or paraesthesia.

On examination, in early stage disease, the clinical examination may be unremarkable. Potential signs include local spinal tenderness or contracted paraspinal muscles, hypomobility, or painful extension of the back or neck. Pain may be reproduced by passively raising the extended leg (positive Lasegue sign), in lumbar disease.

All cases require a complete neurological examination, importantly to assess for evidence of spinal cord compression or cauda equina syndrome.

Further disease progression may demonstrate signs of worsening muscle tenderness, stiffness, reduced movement (particularly lumbar region), and scoliosis.

*Degenerative disc disease can also lead to spinal stenosis, which presents differently in different spine regions e.g. cervical spondylosis which can then present with myelopathic features, or lumbar canal stenosis which can present with a claudication type pattern

Lasègue Test

Lasègue test, also known as the straight leg raise, is used to assess for disc herniation in patients presenting with lumbago.

With the patient lying down on their back, the examiner lifts the patient’s leg while the knee is straight. The ankle can be dorsiflexed and / or the cervical spine flexed for further assessment.

A positive sign is when pain is elicited during the leg raising +/- ankle dorsiflexion or cervical spine flexion. Sensitivity and specificity have been reported at 91% and 26% respectively.

Differential Diagnoses

Important differentials diagnoses to consider include cauda equina syndrome, infection (such as discitis), or malignancy (including metastatic disease)

Red Flags in Back Pain

All patients presenting with back pain should be assessed for the red flag signs, suggestive of a sinister pathology.

Red flag signs include: New-onset faecal incontinence or urinary incontinence; Saddle anaesthesia; Immunosuppression or Chronic Steroid Use; Intravenous Drug User; Unexplained Fever; Significant Trauma, Known Osteoporosis or Metabolic Bone Disease; New Onset aged > 50yrs; Known or Previous Malignancy.

Investigations

Current guidelines suggest imaging should be warranted in cases of suspected degenerative disc disease if:

- Red flags present

- Radiculopathy with pain for more than 6 weeks

- Evidence of a spinal cord compression

- Imaging would significantly alter management

An MRI spine is the gold standard investigation for suspected degenerative disc disease warranting imaging (Fig. 3). Radiological appearances that may be present include signs of degeneration, reduction of disc height, the presence of annular tears, and endplate changes.

Most patients do not require MRI imaging if the symptoms are mild and not progressive, however in those with long-standing and worsening symptoms, MRI is usually the best investigation to also rule out differential diagnosis and formulate management plans.

CT imaging is also a useful tool to assess the bony structures and extent or complications of osteoporosis. Spine plain film radiographs are only recommended if the patient has a history of recent significant trauma, known osteoporosis, or aged over 70 years.

Figure 3 – Sagittal cervical spine MRI demonstrating degenerative disc disease, osteophytes, and osteoarthritis of C5-C6

Management

Management of degenerative disc disease is highly variable and patient-dependent. Broadly, it can be divided into conservative and surgical management.

In the acute stage of disc disease, adequate pain relief is the mainstay of treatment. Simple analgesics should be used first-line, with neuropathic analgesics as adjuncts if required.

Encouraging mobility within patient limits is recommended for the treatment of acute low back pain, with physiotherapy for strengthening exercises. If pain continues beyond 3 months, despite analgesia, referral to the pain clinic may be required.

Surgical Management

Surgical intervention is usually reserved for cases where symptoms have remained severe and progressive despite conservative management. In addition, surgical intervention usually aims to improve radicular symptoms and pain relating to neural compression, but does not improve back pain, which can worsen in the post-operative period.

Surgical options include decompression alone, such as a laminectomy, foraminotomy, to increase the space for the spinal canal and neural fomarina, or decompression with fusion, to provide stability in cases where instability is present. There are various surgical techniques and approaches to achieve this, either open or minimally invasive approaches.

Key Points

- Degenerative disc disease refers to the natural deterioration of the intervertebral disc structure

- The clinical features of degenerative disc disease depend on the region and severity of the disease

- Diagnosis is often clinical and the majority of cases do not require imaging

- Analgesia and physiotherapy is the mainstay of management