Introduction

Ankle fractures are a common injury, more common in younger males or older females, and account for around 10% of all fractures seen in the trauma setting.

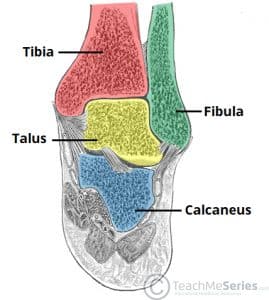

The ankle is comprised of the talus bone articulating within the mortise (Fig. 1); the mortise is comprised of the tibial plafond and medial malleolus (the distal end of the tibia) and the lateral malleolus (the distal end of the fibula).

The tibia and fibula are joined at the syndesmosis, a very strong fibrous structure comprised of the anterior inferior tibiofibular ligament (AITFL), posterior inferior tibiofibular ligament (PITFL), and the intra-osseous membrane.

An ankle fracture* is a fracture of any malleolus (lateral, medial, or posterior), with or without disruption to the syndesmosis.

*Where the tibial articular surface (the plafond) of joint is involved, this is termed a ‘Pilon fracture’ and is considered as a separate injury

Classification

Ankle fractures can be described anatomically. Crudely, they can be described as isolated lateral malleolar fractures, isolated medial malleolar fractures, bimalleolar fractures ( = medial + lateral malleolar fracture), and trimalleolar fractures ( = medial + lateral + posterior malleolar fracture).

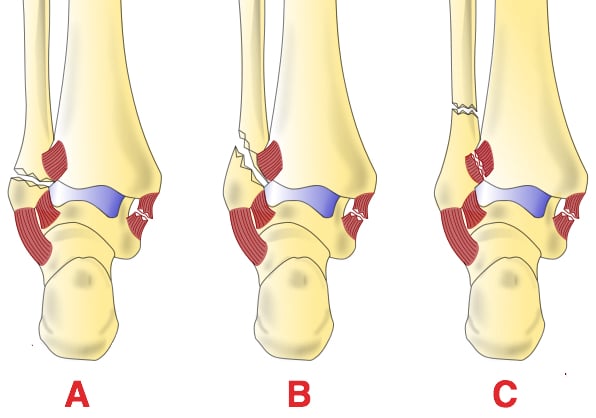

The most common classification used, especially within the Emergency Department, is the Weber classification, which classifies lateral malleolus fractures:

- Type A = below the syndesmosis

- Type B = at the level of the syndesmosis

- Type C = above the level of the syndesmosis

The more proximal the injury, the higher the likelihood of ankle instability; consequently, Type C fractures almost always need surgical fixation.

In orthopaedic practice, the Lauge-Hansen classification is more widely used. This system is based on the ankle position at the time of injury and the deforming force involved, and is much more detailed than the Weber classification.

Clinical Features

Patients will often present with ankle pain following a traumatic injury. There may be associated deformity in cases of fracture dislocation (which require urgent reduction).

Very deformed ankles, which are common, may have neurovascular compromise and are often open fractures (typically over the medial side), so be sure to carefully check the skin integrity.

Ottawa Ankle Rules

Where there is diagnostic uncertainty, for example where the patient is able to mobilise and has no deformity, the ‘Ottawa rules’ can be employed.

These state that in the presence of any of the below features, plain radiographs must be undertaken:

- Bone tenderness at the posterior edge or tip of the lateral malleolus, OR

- Bone tenderness at the posterior edge or tip of the medial malleolus, OR

- An inability to bear weight both immediately and in the emergency department for four steps

Whilst useful, they cannot be used in cases if the patient is intoxicated or uncooperative, has other distracting painful injuries, has diminished sensation in their legs, or has gross swelling.

Investigations

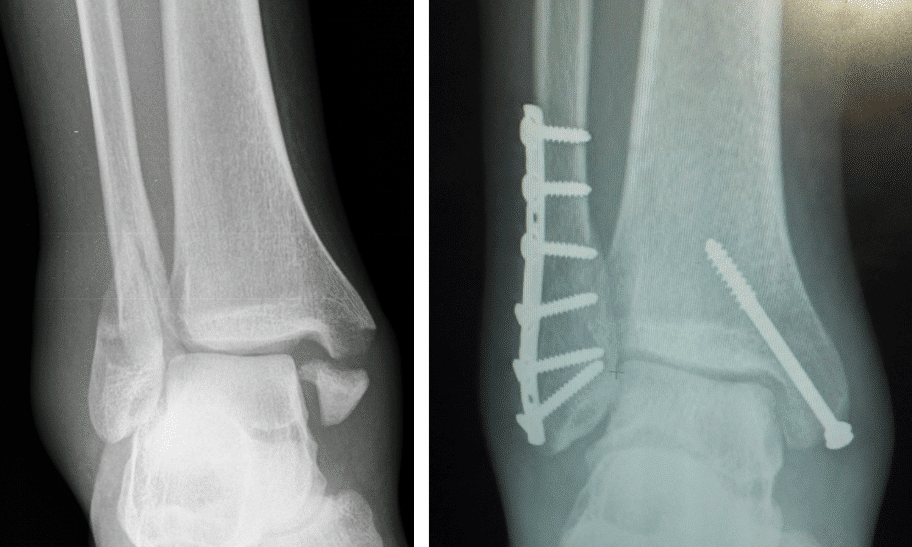

A plain radiograph (Fig. 3) should be obtained in all suspected cases, with both AP and lateral views*. Check the joint space for uniformity, ensuring no evidence of talar shift.

Complex ankle fractures, particularly where there is a displaced posterior malleolus fragment, will require a CT scan for surgical planning.

*It is essential that, when radiographs are taken, the ankle is in full dorsiflexion; this is because the talus, which is narrower posteriorly, can appear translated within the mortise when the ankle in plantarflexed

Management

Initial management requires immediate fracture reduction, usually performed under sedation in the Emergency Department, to realign the fracture to anatomical alignment. Any patients that have with evidence of an open fracture should be managed accordingly.

Once reduced, the ankle should be placed in a below knee back slab. You must then repeat and document the post-reduction neurovascular examination. Request a repeat plain film radiography; if the reduction is not adequate, repeat reduction attempts are required.

Conservative management will often be opted for in:

- Non-displaced medial malleolus fractures

- Weber A fractures or Weber B fractures without talar shift

- Those unfit for surgical intervention

Surgical Management

Open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF) is often required in ankle fractures to achieve stable anatomical reduction of the talus within the ankle mortise. Ankle fractures that require an ORIF include:

- Displaced bimalleolar or trimalleolar fractures

- Weber C fractures

- Weber B fractures with talar shift

- Open fractures

The type of operative procedure performed depends on the specific type of ankle fracture sustained.

Complications

The main complication following an ankle fracture is the risk of post-traumatic arthritis, however this is rare in cases with appropriate reduction and fixation.

Those who have undergone an ORIF have addition risk factors include surgical site infection, DVT or PE, neurovascular injury, non-union, and metalwork prominence.

Key Points

- Ankle fractures are a common fracture type seen in trauma

- Can be classified anatomically into isolated medial malleolar fractures, isolated lateral malleolar fractures, bimalleolar fractures, and trimalleolar fractures

- Ensure to obtain sufficient plain film radiographs in AP and lateral views

- Management depends on the type of fracture sustained, either conservatively or surgically

Ankle Sprain

Ankle sprains are ligamentous injuries and are the main differential for an ankle fracture. They can be classified into high ankle sprains, which are injuries to the syndesmosis, or low ankle sprains, which are injuries to the anterior talofibular ligament (ATFL) and the calcaneofibular ligament (CFL), the latter being much more common.

Patients present following an inversion injury on a plantarflexed ankle. There is often significant swelling and pain, with the patient potentially not being able to weight bear. There is fingertip tenderness distal to the malleoli, over the affected ligaments.

Imaging of choice is with plain film radiographs to rule out any bony injury. Nearly all can be managed conservatively with analgesia, ice, and elevation, following by early mobilisation.