Introduction

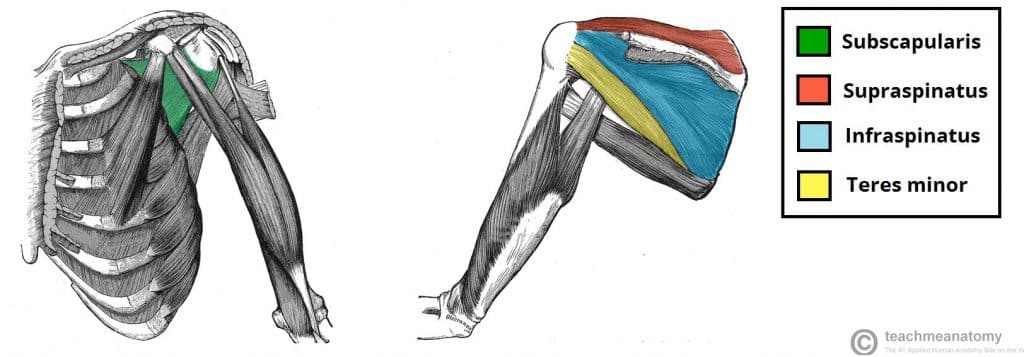

The rotator cuff is a group of 4 muscles that support and rotate the glenohumeral joint (Fig. 1). Alongside their role in movement of the shoulder, the rotator cuff muscles act to stabilise the humeral head in the glenoid fossa.

Rotator cuff tears are common; acute full thickness tears have an incidence around 2.5 per 10,000 patients for those aged 40-70yrs, whilst the prevalence of a rotator cuff tear (of all degrees) in the general population is around 20%.

Classification

Rotator cuff tears are classified as either acute (lasting <3 months) or chronic (lasting >3 months) tears. They can be either partial thickness or full thickness tears.

Full thickness tears can be further classified into small (<1cm), medium (1-3cm), large (3-5cm), or massive (>5cm or involves multiple tendons) tears.

The Rotator Cuff Muscles

The rotator cuff is composed of four muscles:

- Supraspinatus – abduction

- Infraspinatus – external rotation

- Teres minor – external rotation (and adduction)

- Subscapularis – internal rotation

Pathophysiology

Acute tears commonly occur within tendons with pre-existing degeneration, typically occurring alone following minimal force. However, acute tears can occur in young individuals subjected to a larger force, often alongside other injuries.

Chronic tears occur in individuals with degenerative microtears to the tendon, most commonly from overuse and seen in greater incidence with increasing age.

Risk Factors

The main risk factors for rotator cuff tears are increasing age, significant trauma, and repetitive overhead shoulder motions (e.g. athletes). Other risk factors include obesity, smoking, and diabetes mellitus.

Clinical Features

Patients will present with pain over the lateral aspect of shoulder and an inability to abduct the arm above 90 degrees. Tears are more common in the dominant arm.

On examination, there is often tenderness over the greater tuberosity and subacromial bursa regions. Supraspinatus and infraspinatus atrophy can be seen in massive rotator cuff tears.

Specific Tests

There are specific tests that can be performed to help clinically assess for the presence of a rotator cuff tear and elucidate which tendon(s) are affected:

- Jobe’s test (tests supraspinatus) – place the shoulder in 90° abduction and 30° of forward flexion and internally rotate fully (as if you’re “emptying a can”), gently push downwards on the arm.

- A positive test is present if there is weakness on resistance

- Gerber’s lift-off test (tests subscapularis) – internally rotate the arm so the dorsal surface of hand rests on lower back, then ask the patient to lift hand away from back against examiner resistance

- A positive test is weakness in actively lifting the hand away from back (compare to the contralateral side)

- Posterior cuff test (tests infraspinatus and teres minor) – the arm positioned at patient’s side, with the elbow flexed to 90°, then the patient is instructed to externally rotate their arm against resistance

- A positive test is present if there is weakness on resistance

Differential Diagnoses

The main differentials to be considered include fracture, persistent glenohumeral subluxation, brachial plexus injury, or radiculopathy.

Investigations

Patients presenting with clinical features of a rotator cuff tear should have an urgent plain film radiograph to exclude a fracture*.

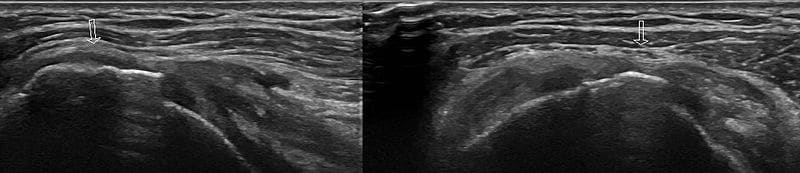

Once a fracture has been excluded, rotator cuff tears can be assessed through further imaging. Ultrasonograhy can establish the presence and size of tear (Fig. 2), whilst MRI imaging can also be used to detect the size, characteristics, and location of the tear.

*Whilst most plain film radiographs will be unremarkable, in chronic tears, there may be evidence of reduced acromiohumeral distance or sclerosis and cyst formation the rotator cuff insertion on the greater tuberosity

Management

Management is dependent on the type of tear and functional status of the patient.

Conservative management is preferred in patients who are not limited by pain or loss of function, or those who have significant co-morbidities and unsuitable for surgery. Indeed, those who are presenting within 2 weeks since injury can be managed conservatively, with the mainstay of this being both analgesia and physiotherapy, with activity modification.

Surgical Management

For those presenting 2 weeks since the injury or remaining symptomatic despite conservative management may be referred for surgical intervention. Large and massive tears should also be considered for surgical repair.

Repairs can be done arthroscopically (allowing for earlier recovery) or via open approach (preferred in large or complex tears)

Prognosis following surgical repair overall tends to be good, however those with large or massive tears, aged >65yrs, poor compliance with rehabilitation programs, or current smokers may have worse outcomes.

Prognosis

The main complication from the condition is adhesive capsulitis, leading to stiffness of the glenohumeral joint.

Around 40% of those with age-related tears will have enlargement of their tears within 5 years. Of those whose tears enlarge, 80% will become symptomatic.

Key Points

- Rotator cuff tears are classified as either acute (lasting <3 months) or chronic (lasting >3 months)

- Patients will present with pain over the lateral aspect of shoulder and an inability to abduct the arm above 90 degrees

- Once fracture has been excluded, either ultrasound or MRI imaging can be used to further assess the condition

- The condition can be managed both conservatively or surgically