Introduction

Melanoma is a malignant tumour of melanocytes, the melanin-producing cells of the body. It commonly arises from melanocytes in the stratum basale of the epidermis but can also arise from melanocytes at other sites.

Melanin itself is produced in response to UV radiation exposure and acts to protect against DNA damage by dissipating >99.9% of absorbed radiation.

Melanoma most commonly affects the trunk or legs, with incidence rising with age. They metastasise early (relative to other skin cancer types), partly due to their vertical growth (as opposed to radially).

Histological Subtypes

The four main histological subtypes of melanoma are listed in the table below:

| Type | Proportion | Typical Location | Features |

|

Superficial spreading |

60% |

Any site | Large, flat, and irregularly pigmented lesion, typically in those aged 30-50yrs |

|

Nodular |

30% |

Any site | Rapidly growing, pigmented, bleeding, or ulcerated nodule, typically in those >50yrs |

|

Lentigo maligna melanoma* |

7% |

Head and neck | Large flat pigmented lesions, often in the older population |

|

Acral lentiginous |

2% |

Palms, soles, or under the nails | Variable pigmentation, often present with appearance of a stain, typically large size at presentation |

Table 1 – Main subtypes of skin melanoma

*Lentigo maligna is a macular lesion containing an increased number of abnormal melanocytes, confined to epidermis (aka melanoma in situ), whilst lentigo maligna melanoma are when these abnormal melanocytes invade the dermis

Pathophysiology

The exact pathophysiology of melanoma remains unclear. However, the main contributor is ultraviolet (UV) radiation exposure.

Genetic mutations may also increase the susceptibility to carcinogenic effects of UV radiation; two main mutations include:

- MAPK pathway – mutations to proto-oncogenes, such as BRAF and NRAS, which normally promote cell proliferation and survival, result in activation of MAPK pathway, which causes uncontrolled cell proliferation*

- CDKN2A/RB1 pathway – CDKN2A encodes the p16 and p14ARF proteins, both of which act as tumour suppressors by regulating the cell cycle (specifically, by blocking transition from the G1 to S-phase); mutation to CDKN2A can result in unregulated cell growth and neoplastic progression.

*Approximately 50% of melanomas are BRAF positive, specifically NRAS mutations are present in ~20% of melanomas

Risk Factors

There are multiple risk factors for the development of melanoma:

- UV exposure – both recreational (e.g. sunbed use) and occupational

- Age – the majority of melanomas occur in patients aged >50yrs

- Previous melanoma – represents an 8-10x increased risk

- Skin tone – incidence is highest in Caucasian groups (although prognosis in darker skin is worse due to delayed diagnosis)

- Most commonly affects Fitzpatrick Type 1 and 2 skin, the two palest skin types

- Family history – approximately 10% of patients will have a positive family history for melanoma

- Predisposing conditions – albinism, xeroderma pigmentosum, atypical mole syndrome, >50 typical naevi, immunosuppression (i.e. organ transplant recipient)

Clinical Features

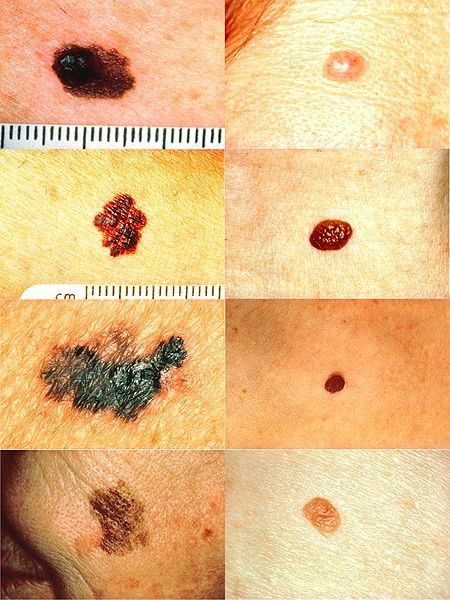

Melanoma presents as a new skin lesion or a change in the appearance of a pre-existing mole. There may be associated bleeding or itching.

An important component of the history is assessing for the risk factors (as mentioned above), as this will aid in triaging the patient effectively.

Upon examining the skin lesion, the ABCDE rule is helpful:

- Asymmetry

- Border irregularity

- Colour uneven

- Diameter >6mm

- Evolving lesion

Dermoscopy can also aid the assessment of pigmented lesions and may show features specific to melanoma. The patient should also be fully examined for features of spread, such as lymphadenopathy in the draining lymph nodes.

Differential Diagnoses

There are numerous pigmented skin lesions that can mimic the appearance of melanoma, which can be divided into benign and malignant groups:

- Benign = Junctional or compound naevi, intradermal naevi, blue naevi, spitz naevi, seborrheic keratosis.

- Malignant = Pigmented basal cell carcinoma, kaposi sarcoma

Investigations

The diagnosis of melanoma is made through an excisional biopsy. The standard excision biopsy requires a 2mm peripheral margin and a cuff of subcutaneous fat at the deep margin.

On certain occasions, it may be more appropriate to perform an incisional biopsy in large lesions where complete excision would leave a sizeable skin defect. Suspected subungal melanomas may also be more appropriate for incisional biopsy.

Histological Features of Melanoma

Key histopathological features that can be identified following biopsy for a suspected melanoma, which can determine both management or prognosis, include:

- Breslow thickness (distance between the stratum granulosum and the deepest point of the melanoma)

- Degree of ulceration

- Histological subtype

- Immunohistocytochemistry (to identify any genetic markers, such as BRAF status, present)

- Mitotic rate (number of mitotic figures per square millimeter)

Management

Patients with a tissue diagnosis of melanoma should be referred to the specialist skin MDT (ssMDT), where definitive excision margins, further investigations, and treatment are determined.

In all cases of melanoma, ongoing sun protection advice should be given, with concurrent Vitamin D supplementation and advice on prevention (see Prognosis).

Wide Local Excision

A wide local excision refers to excision of a larger area of tissue from the original site of the melanoma. Its aim is to improve local control of melanoma by removing micrometastases.

It is indicated is nearly all cases of melanoma, including those with clear histological margins on the excision biopsy.

The exact peripheral margin used in the wide local excision is guided by the Breslow thickness (Table 2). The deep margin should always be down to the deep fascia.

|

Breslow Thickness |

Peripheral Margins |

|

In-situ melanoma |

0.5cm |

|

≤1mm |

1cm |

|

1-2mm |

1-2cm |

| 2-4mm |

2-3cm |

| >4mm |

3cm |

Table 2 – Guide peripheral margins for WLE, however practice may vary between centres depending on local guidelines

Sentinel Lymph Node Biopsy

Sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) aims to identify whether or not there is any melanoma in the primary draining lymph node(s) within a regional lymph node basin.

Current NICE guidelines recommend offering SLNB to patients with melanoma with a Breslow thickness >1 mm, without clinically apparent nodal or metastatic disease.

If the lymph nodes are clinically suspicious (i.e. palpable) or radiologically suspicious (i.e. enlarged on imaging) then fine needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) should be performed.

When obtaining patient content for SLNB, it is important to emphasis that it is a staging and prognostic procedure only. It is usually performed at the same time as the wide local excision.

Staging

Imaging should be performed in patients with stage IIc melanoma who have not had SLNB, or stage III and IV melanoma. Typically, this involves a CT chest-abdomen-pelvis and MRI brain (or whole body PET-CT with additional imaging of the brain).

Melanoma is staged using the TNM classification; the clinical TNM (cTNM) stage is then updated with information after surgery to give the pathological stage (pTNM).

The AJCC staging (Table 3) groups the TNM stages to guide treatment and prognosis.

| Stage | TNM |

Description |

| Stage 0 | Tis, N0, M0 | Melanoma in situ |

| Stage I A/B | A = T1a, N0, M0

B = T1b, N0, M0 or T2a, N0, M0 |

<1 mm thickness melanoma, or 1-2 mm thickness non-ulcerated melanoma |

| Stage II A/B/C | A = T2b, N0, M0 or T3a, N0, M0

B = T3b, N0, M0 or T4a, N0, M0 C = T4b, N0, M0 |

1-2 mm thickness ulcerated melanoma, or >2 mm thickness melanoma |

| Stage III A/B/C | any T, N 1-3, M0 | Nodal metastasis |

| Stage IV | any T, any N, M1a, M1b or M1c | Systemic metastasis |

Table 3 – The AJCC staging system

Metastatic Disease

Unfortunately, metastatic disease is relatively common in melanoma. Both regional and distant metastases can be managed using various immunotherapy and chemotherapy agents.

The immunotherapy agents most commonly used are:

- Ipilimumab – a monoclonal antibody that inhibits cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen 4 (CTLA 4), which would normally down regulate T cell activation

- Pembrolizumab and Nivolumab – monoclonal antibodies that attach to the PD1 receptor on T cells so that the T cells cannot be switched off and remain active

- Vemurafenib and Dabrafenib – both are BRAF kinase inhibitors that block the activity of the BRAF V600E mutation which otherwise causes persistent MAPK pathway activation leading to uncontrolled cell proliferation

- Talimogenelaherparepvec (TVEC) – an oncolytic immunotherapy derived from herpes simplex virus type-1 which causes tumour lysis and the release of tumour-derived antigens; it is injected directly into the metastasis

Prognosis

Melanoma survival is strongly correlated with histopathological and individual features. Approximate 5-year survival, based on disease stage are:

- Stage 1 – 100%

- Stage 2 – 80%

- Stage 3 – 70%

- Stage 4 – 30%

Prevention is the best management option through education encouraging reducing exposure to UV light through sun-protection and avoidance of sun beds, and self-checking for new or changing skin lesions. Patients at high risk for melanoma should receive annual screening.

Key Points

- Melanoma is a malignant tumour of melanocytes, the melanin-producing neural crest-derived cells of the body

- The main risk factor for its development is UV exposure

- Diagnosis is made through excision biopsy, subsequent excision margins are guided by Breslow thickness

- Systemic metastases can be treated using various immunotherapies and chemotherapies