Introduction

The trachea is a D-shaped fibrocartilaginous tube which runs from the larynx, continuing inferiorly posterior to the sternum, before dividing into the right and left primary bronchi at the carina (around T4 vertebral level).

The tracheal cartilages are composed of hyaline cartilage which act to support the trachea and stop it from collapsing during the pressure changes that occur during air ventilation (Fig. 1). The trachealis muscle bridges the gap between the free ends of C-shaped cartilage rings at the posterior border of the trachea.

Tracheomalacia and tracheal stenosis are the two most common conditions that affect the trachea, whilst other less common conditions include tracheooesophageal fistulae or tracheal tumours. This article will focus on the management of the tracheal stenosis and tracheomalacia.

Tracheomalacia

Tracheomalacia involves progressive weakening of the tracheal walls, resulting in airway collapse on expiration. Majority of patients will present in younger years, as babies or in early childhood.

There are three types of tracheomalacia:

- Type 1 = congenital causes, can be associated with tracheoesophageal fistula or oesophageal atresia

- Type 2 = extrinsic compression, such as a thyroid goitre or mediastinal mass

- Type 3 = acquired, such as from previous prolonged intubation, COPD, or trauma

Clinical Features

In congenital cases, children will present with difficulty breathing or stridor (the most common cause of stridor in children), which is made worse when supine or when feeding or crying. It can also result in recurrent lower respiratory tract infections.

In acquired cases, patients can present with shortness of breath on exertion or recurrent pneumonia, or in severe cases with stridor. In patients on intensive care following prolonged intubation, cases might be suspected if there is difficulty in extubating the patient.

Investigations

Gold standard for diagnosis is bronchoscopy which can reveal anterior and/or posterior collapse of tracheal lumen during expiration.

Tracheomalacia is considered mild if the trachea lumen is <50% of initial size during expiration, moderate if it narrows to 25%, and severe if the tracheal walls oppose.

Management

Management of tracheomalacia depends on the extent of airway collapse. Symptoms of minor airway collapse will often improve during childhood.

However, if the airway collapses and respiratory compromise is severe, both children and adults will typically require stent insertion or surgical repair.

Patients can undergo a stent trial (Y-shaped silicone stent) for 2 weeks to see if symptoms improve. Should symptoms improve, patients may be offered a tracheoplasty or tracheobronchoplasty.

Complications

Symptoms of tracheomalacia often resolve by 18-24 months, particularly when tracheostomy has been used to function as a stent in the airway until maturation of cartilage occurs to reinforce structural integrity. Complications are rare, but mucus plugs are a potential complication during the 2-week stent trial.

Tracheal Stenosis

Tracheal stenosis is narrowing of the trachea. This can also be either congenital or acquired in nature, however, is most commonly post-tracheostomy* or as a pressure injury from endotracheal intubation.

*Most commonly as a result of prolonged endotracheal intubation, prior tracheostomy, or if tracheostomy is too high (resulting in subglottic injuries)

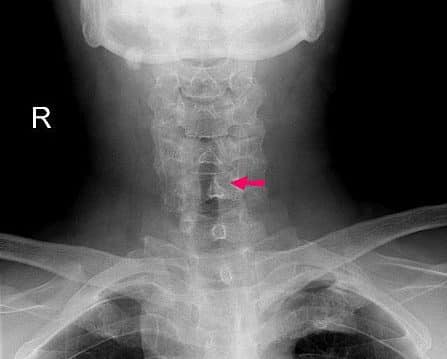

Figure 2 – Plain film radiograph showing a subglottic stenosis post-intubation, with a narrowing in the tracheal lumen (arrow)

Clinical Features

Symptoms of tracheal stenosis can take up to 6 weeks to appear after extubation, however should be suspected in cases in difficult or prolonged intubations.

Patients will present with features of shortness of breath and progressive upper airway obstruction (including stridor).

Investigation

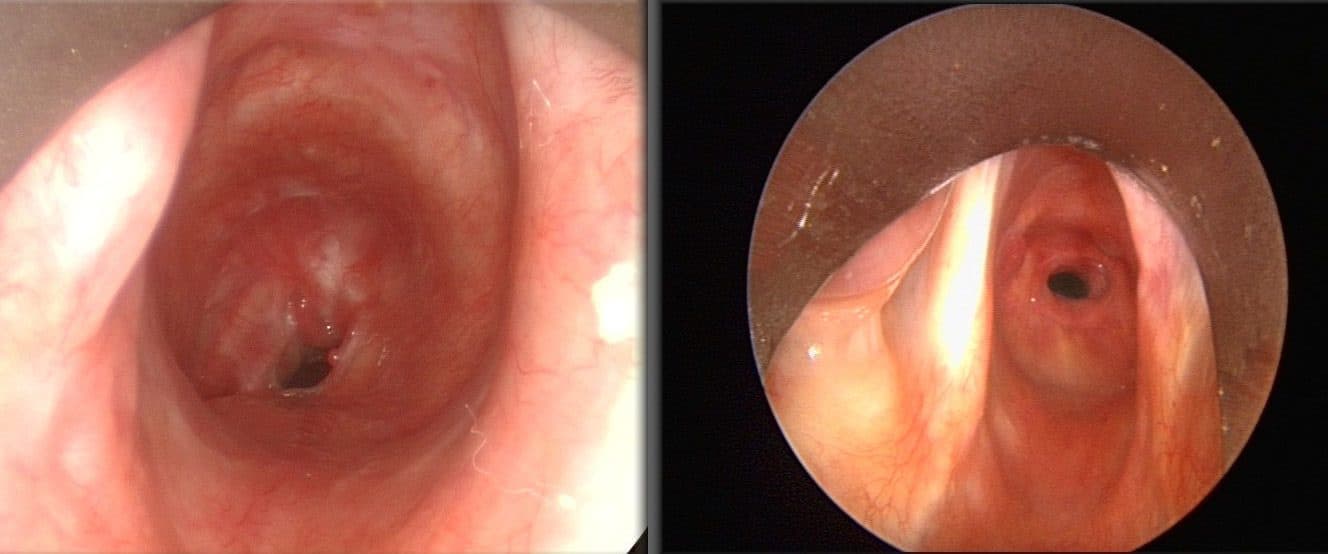

Bronchoscopy is required for all patients with suspected tracheal stenosis (Fig 3). Similar to tracheomalacia, patients should be awake to enable vocal cord assessment.

Tracheal CT scan, specifically spiral CT scan with 3D reconstruction, is often now used to further aid the diagnosis of tracheal stenosis.

Figure 3 – Bronchoscopy demonstrating tracheal stenosis

Management

Surgical options vary depending on the cause and extent of disease:

- Dilation via a balloon, guidewire, or rigid bronchoscope; this approach is indicated when there is inflammation in the segment to be resected and allows time for the inflammation to subside before definitive surgery

- For definitive treatment, tracheal resection and reconstruction of the stenotic segment is required; in congenital stenosis, tracheoplasty is also an option

Key Points

- Tracheomalacia and tracheal stenosis are the two most common conditions that affect the trachea

- Tracheomalacia involves progressive weakening of the tracheal walls, resulting in airway collapse on expiration, most common in early years

- Tracheal stenosis is narrowing of the trachea and this common occurs post-tracheostomy