Introduction

Urinary retention is as an inability to pass urine. It can be divided into acute or chronic urinary retention

Chronic urinary retention is the painless inability to pass urine*. These patients have long standing retention, therefore have significant bladder distension which results in bladder desensitisation, therefore minimal discomfort despite potential large intra-vesical volumes.

*Some patients may pass small quantities of urine, however still have significant residual volumes, therefore are still defined as having chronic urinary retention

Pathophysiology

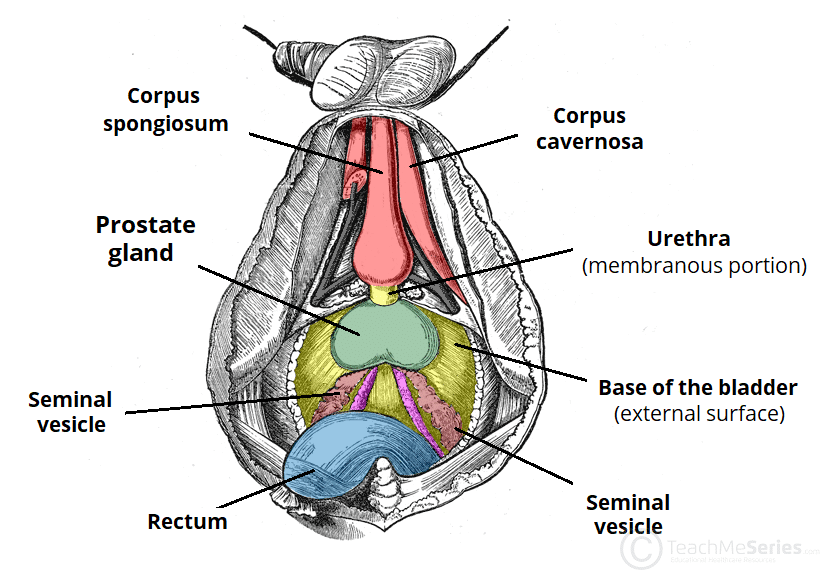

The most common cause in men is Benign Prostate Hyperplasia (BPH). Other common obstructive causes include urethral strictures or prostate cancer.

In women, pelvic prolapse (such as cystocele, rectocele, or uterine prolapse) or pelvic masses (such as large fibroids) can also cause chronic retention.

Neurological causes can also cause chronic retention, including peripheral neuropathies or upper motor neurone disease (such as Multiple Sclerosis or Parkinson’s disease).

Clinical Features

Patients will present with painless urinary retention. They may have associated voiding LUTS, such as weak stream and hesitancy, with a reduced functional capacity (the ability of the bladder to store urine before producing urge to void).

Overflow incontinence may also be present, whereby the intra-vesical pressures rise greater than those of the urinary sphincter. This is typically worse at night (nocturnal enuresis), when the sphincter tone is reduced.

On examination, there will be a palpable distended bladder, with no or minimal tenderness. Ensure to perform a rectal examination (in men) to assess for evidence of prostate enlargement.

Investigations

A post-void bedside bladder scan will show volumes of retained urine, also helping to confirm the diagnosis.

All patients should undergo routine bloods, especially a FBC, CRP, and U&Es. Patients with features of high-pressure chronic retention (HPCR, see below) will require an ultrasound scan of their urinary tract to assess for the presence of associated hydronephrosis.

If there is a large volume of urine drained on catheterisation (>1000ml), then HPCR should be ruled out. If the patient is found to have bilateral hydronephrosis or an acute kidney injury with no other cause, then the patient is likely to have HPCR.

High-Pressure Urinary Retention

High Pressure Urinary Retention refers to the urinary retention causing such high intra-vesicular pressures that the anti-reflux mechanism of the bladder and ureters is overcome and ‘backs up’ into the upper renal tract leading to hydroureter and hydronephrosis, impairing the kidneys’ clearance levels.

Such patients present in retention with associated deranged renal function, and hydronephrosis will be subsequently confirmed on imaging (typically ultrasound as first line). Repeat episodes of high-pressure chronic retention can cause permanent renal scarring and chronic kidney disease (CKD).

By contrast, low pressure retention occurs in patients with retention with the upper renal tract unaffected due competent urethral valves or reduced detrusor muscle contractility / complete detrusor failure.

Management

Patients with very high post-void volumes (arbitrarily >1L) or evidence of high pressure retention should be catheterised with a long-term catheter. Those with high post-void volumes should also have urine output monitored for post-obstructive diuresis.

Post-Obstructive Diuresis

Following resolution of the retention through catheterisation, the kidneys can often over-diurese due to the loss of their medullary concentration gradient, which can take time to re-equilibrate.

This over-diuresis can lead to a worsening AKI. Consequently, those patients at risk should have their urine output monitored over the following 24 hours post-catheterisation.

Patients producing >200ml/hr urine output for ≥2 hours should have around 50% of their urine output replaced with intravenous fluids to avoid any worsening AKI.

The patients should not undergo a Trial WithOut Catheter (TWOC), especially if evidence of high-pressure chronic retention, due to concerns of repeat renal injury. Instead they should have a long-term catheter before definitive management is planned; alternatives to this include Intermittent Self Catheterisation (ISC) or suprapubic catheterisation.

Definitive management of chronic retention depends on the underlying cause. Consider starting an alpha-1 adrenoreceptor antagonist in all men with a history of chronic voiding symptoms or a palpably large prostate. Those with low residual volumes can have a TWOC >72hrs after commencement.

Intermittent Self Catheterisation

Intermittent Self Catheterisation (ISC) can be used in patients with chronic urinary retention, for those who wish to avoid a long-term catheter

Patients are taught how to catheterise themselves at regular intervals (e.g. every 4-6hrs), however requires good manual dexterity and patient compliance, therefore is not suited for all patients.

Complications

Due to stasis of urine, patients with chronic retention are more likely to develop urinary tract infections and form bladder calculi.

Repeat episodes of unmanaged high-pressure retention can lead to chronic kidney disease.

Key Points

- Chronic urinary retention is the painless inability to pass urine

- Most common cause is benign prostatic hyperplasia

- Investigate all cases with post-void bladder scan and routine bloods

- Severe cases will require catheterisation, before definitive management of the underlying cause is achieved.