Introduction

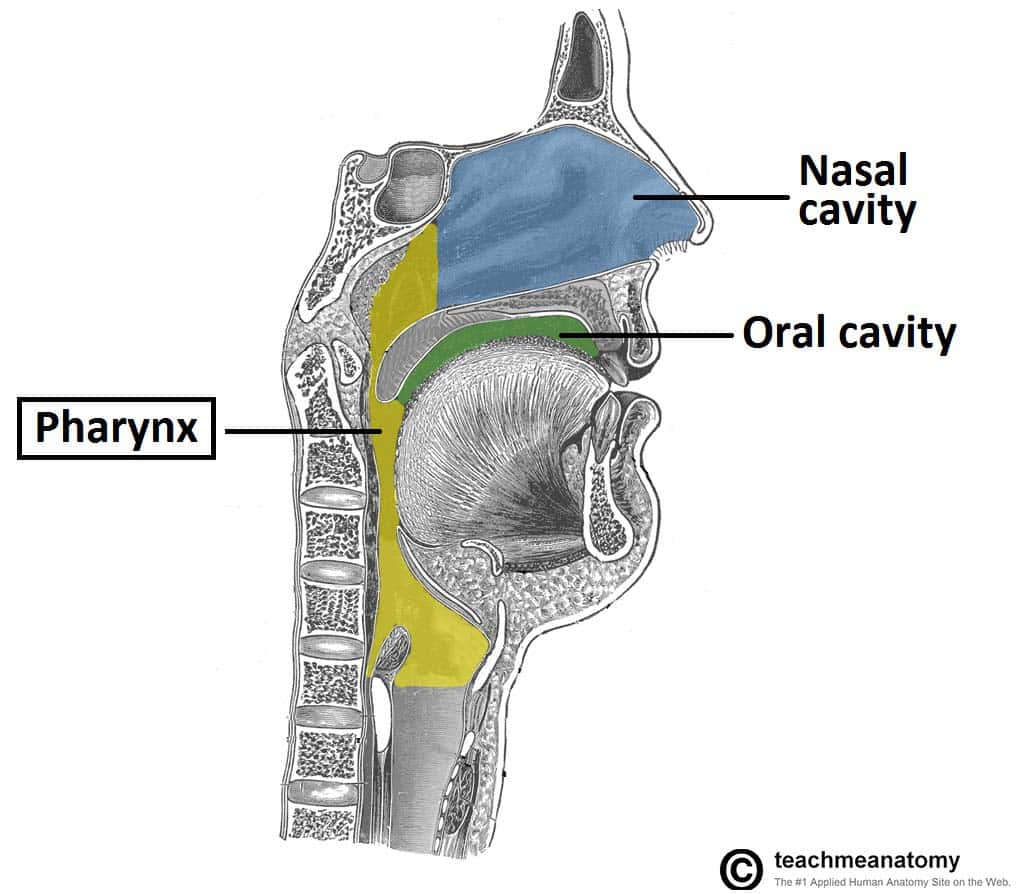

Head and neck cancers refer to malignancies of the upper aerodigestive tract, which includes the oral cavity, oropharynx, hypopharynx, larynx, paranasal sinuses and nasal cavity). Officially, they include malignancies of the cervical oesophagus, thyroid gland, or salivary glands, which are discussed elsewhere.

The most common malignancy of the head and neck is squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). Other subtypes are adenocarcinomas of the salivary glands and mesenchymal lesions of the soft tissues and paranasal sinuses.

In the UK, around 10,000 new cases of Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinomas (HNSCCs) are diagnosed each year, whilst in the US they account for 3-4% of all malignancies diagnosed. They are at least twice as common in males, with a rising incidence; of note:

- Oral cavity cancer incidence is increasing, thought to be linked to immigration and betel quid chewing especially in the Indian subcontinent

- Oropharyngeal cancer incidence is increasing, thought to be linked to Human Papillomavirus (HPV) affecting the younger population

- Laryngeal cancer incidence is decreasing, likely due to reduced smoking rates worldwide

Risk Factors

Most HNSCCs are linked to modifiable behaviours, with alcohol and tobacco use account for around 75% of HNSCCs.

Other risk factors include HPV (mainly type 16, most significantly linked to oropharyngeal cancer), betel quid (linked to oral cancer), occupational wood dust or asbestos exposure (linked to sinonasal cancer), and EBV infection (linked to nasopharyngeal cancer).

Immunodeficiency due to HIV infection or organ transplantations has been found to be a risk factor for increased risk of HNSCCs. Prior radiation to the head and neck region is also a known risk factor, especially for thyroid cancer and salivary gland tumours.

Premalignant Conditions

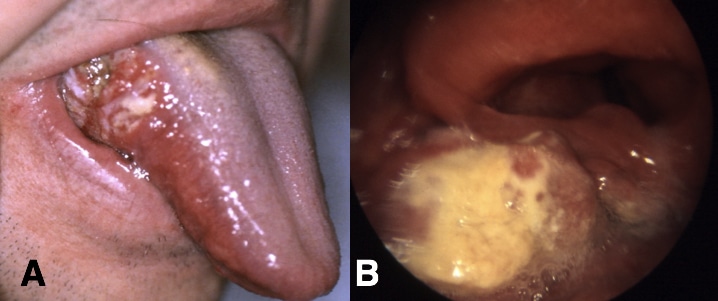

Many HNSCCs, typically the oral cancers, may begin as a visible premalignant condition, such as leukoplakia (white patches), erythroplakia (red patches), erythroleukoplakia (mixed red and white patches), oral lichen planus, or actinic cheilitis.

These premalignant conditions are also heavily associated with smoking and alcohol consumption, and have a lifetime risk of transformation ranging from 0-20%. Consequently, most suspected premalignant conditions require further histological assessment via biopsy.

Clinical Features

Each subtype of HNSCCs can present differently, however it is important to remember non-specific symptoms, such as weight loss, night sweats, loss of appetite, or cervical lymphadenopathy can also be a feature.

Oral Cavity Cancer

Most commonly oral cavity cancers will present as a mass, typically painless, being felt on the inner lip, tongue, floor of the mouth, or hard palate. Less commonly, these cancers will present in more non-specific means*, such as oral cavity bleeding, localised pain within the oral cavity, neck lump or jaw swelling.

*Premalignant conditions (erythroleukoplakia) may be noticed initially, prompting further investigations which reveal the malignant transformation

Oropharyngeal cancer

The subsites of the oropharynx are tonsil, base of tongue, soft palate and pharyngeal walls. Patients present with odynophagia, dysphagia, tonsillar lump or an asymmetrical tonsil, a neck lump, or a feeling of “something in the throat”

Hypopharyngeal Cancer

Subsites of the hypopharynx include the pyriform sinuses, the postcricoid region, and the posterior pharyngeal wall. Many cases of hypopharyngeal cancer can present initially as odynophagia, dysphagia, stertor, or referred otalgia.

Majority of these tumours, specifically of the hypopharynx, frequently will have an advanced stage at the time of diagnosis as they will often metastasise early due to the extensive lymphatic network.

Nasopharyngeal Cancer

Most cases of nasopharyngeal cancer patients present initially with a neck lump or unilateral conductive hearing loss*. Therefore, any adult patient presenting with conductive hearing loss should be examined with a flexible nasoendoscope to look at the post-nasal space, especially at the fossa of Rosenmüller. Otherwise, patients of later stages will present with unilateral nasal symptoms of nasal obstruction, epistaxis, or discharge.

*Trotters Syndrome is a triad of clinical features suggestive of nasopharyngeal malignancy, comprised of (1) unilateral conductive deafness (secondary to middle ear effusion), (2) trigeminal neuralgia (secondary to perineural invasion), and (3) defective mobility of the soft palate

Laryngeal Cancer

The clinical features of a laryngeal malignancy can include hoarse voice, stridor (if advanced), dysphagia, persistent cough, or referred otalgia. Laryngeal cancers are divided anatomically (mainly for the purpose of tumour staging) into glottis, supraglottis, and subglottis, with most malignancies originating in the glottis region.

Patients with glottic tumours have a better prognosis, as they present earlier with hoarse voice and there is no lymphatic drainage from the glottis, hence limits any metastatic spread locally.

Investigations

The mainstay of investigation for suspected HNSCC requires biopsy of the lesion, the method by which this is obtained depends on the location.

Most referrals for suspected HNSCCs undergo flexible nasendoscopy (FNE), allowing for direct visualisation of the lesion. If a lesion is seen, then a microlaryngoscopy or panendoscopy and biopsy will be warranted for a complete assessment*

For those patients presenting solely with lymphadenopathy, they will undergo ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration (FNA) of the lymph node to assess for evidence of malignant cells.

*In most cases, a biopsy will need to be performed under general anaesthetic with the exception of oral cavity lesions

Staging

MRI imaging of the head and neck is the imaging modality of choice for any suspicious HNSCCs.

If there is a high index of suspicion, the patient will require a CT scan of the neck and chest used to estimate tumour extension, evidence of local invasion, and any cervical lymphadenopathy, alongside evidence of lung metastasis.

PET-CT scan is often the first line investigation for primary tumours of unknown origin (defined as patients presenting with a malignant lymph node but no primary source has been identified).

Referrals

Current NICE guidance suggests that referral to a specialist centre is warranted when patients present with:

- Laryngeal Cancer

- Persistent unexplained hoarseness (urgent)

- Unexplained lump in the neck (urgent)

- Oral Cancer

- Lump on the lip or in the oral cavity (urgent)

- Erythroplakia or erythroleukoplakia (urgent)

- Unexplained ulceration in the oral cavity for >3 weeks (consider)

- Persistent and unexplained lump in the neck (consider)

Management

Management of HNSCCs varies greatly depending on the location, size, stage, and grade of the cancer, as well as patient preference and co-morbidities.

Additionally, these patients are often heavy smokers or alcohol drinkers who require support with smoking and alcohol cessation. Considerations are also required with regards to nutrition with route of feeding, and assessment of dental health prior to radiotherapy.

Surgical resection +/- adjuvant radiotherapy or chemotherapy or primary radiotherapy +/- adjuvant chemotherapy are the main treatment options for most HNSCCs. The management plan should be discussed and planned in a dedicated head and neck MDT meeting.

Oral cavity

Small tumours can undergo wide local excision +/- neck dissection. Recent evidence shows improved survival for patients with oral cavity cancers undergoing elective neck dissection regardless of tumour size.

Advanced tumours should undergo surgical resection +/- flap reconstruction + neck dissection +/- post-operative radiotherapy +/- chemotherapy.

Oropharynx

Small tumours of the tonsil can undergo surgical resection using Laser or Transoral Robotic Surgery +/- neck dissection or primary radiotherapy or both (if margin involved). More advanced tumours of the tonsil can undergo solely primary radiotherapy +/- adjuvant chemotherapy.

Small tumours at the tongue base can undergo surgical resection using Transoral Robotic Surgery with neck dissection or primary radiotherapy or both (if margin involved). Larger tumours at the tongue base can undergo primary radiotherapy +/- adjuvant chemotherapy.

Larynx

Supraglottis

Small tumours can undergo surgical resection using transoral laser microsurgery with bilateral neck dissection or primary radiotherapy +/- adjuvant chemotherapy.

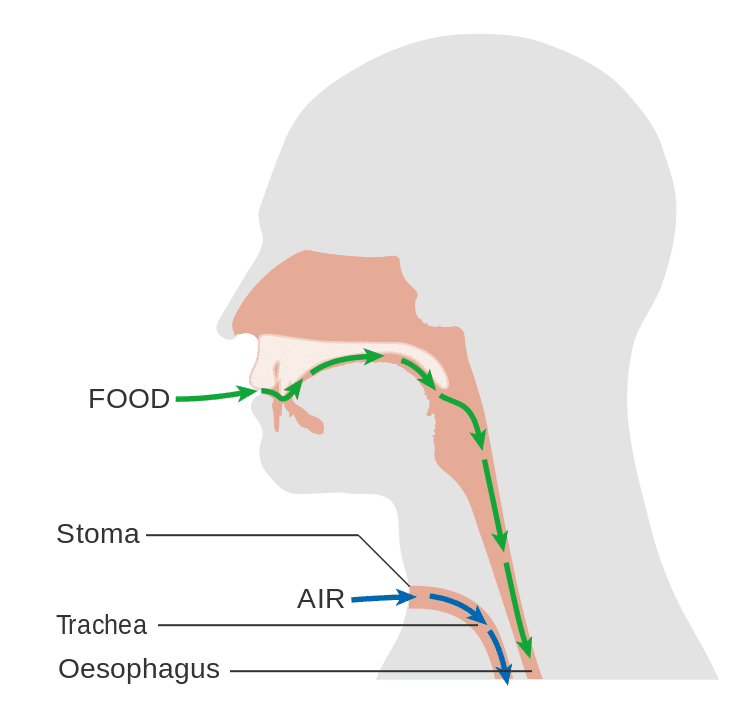

Advanced tumours can undergo laryngectomy with post-operative radiotherapy +/- adjuvant chemotherapy or primary radiotherapy +/- adjuvant chemotherapy.

Glottis

Small tumours can have surgical resection using transoral laser microsurgery with bilateral neck dissection or primary radiotherapy.

Advanced tumours can undergo laryngectomy with neck dissection and post-operative radiotherapy +/- adjuvant chemotherapy or primary radiotherapy +/- adjuvant chemotherapy.

Subglottis

Tumours originating from the subglottis are very rare but treatment principles are similar to the glottis.

Figure 3 – Schematic demonstrating the anatomy of the neck, following laryngectomy

Hypopharynx

Small tumours of the hypopharynx can undergo surgical resection using transoral laser microsurgery with neck dissection or primary radiotherapy +/- adjuvant chemotherapy

Advanced tumours should undergo laryngopharyngectomy +/- gastric pull up/jejunal free flap + neck dissection or primary radiotherapy +/- adjuvant chemotherapy

Prognosis

Prognosis is varied, mainly dependent on the subtype and TNM staging (Table 1). Of note, newer classifications have included separate sections for HNSCC secondary to HPV, however these are often not universally used.

|

Site |

Stage |

All Stages |

|||

| I | II |

III |

IV |

||

| Oral cavity | 75.6% | 70.3% | 62.7% | 30.5% | 50.2% |

| Oropharynx | 80.3% | 64.8% | 51.5% | 31.4% | 40.6% |

| Hypopharynx | – | 32.9% | 48.5% | 20.0% | 28.1% |

| Supraglottis | 89.9% | 73.0% | 73.2% | 41.8% | 62.4% |

| Glottis | 94.0% | 86.7% | 72.3% | 52.4% | 85.9% |

| Subglottis | – | – | – | – | 44.4% |

Table 1 – Five Year Recurrence Free Survival Rates for Head and Neck Cancers, data adapted from Iro H et al.

A proportion of those treated for head and neck cancers will develop secondary primary malignancies, with rates at 20 years ranging from 9-23%, hence can have an impact on long-term survival after successful treatment of early-stage HNSCC.

Alongside disease recurrence, other complications following treatment for head and neck cancers include:

- Dysphagia (secondary to pharyngeal/oesophageal stricture)

- Pharyngocutaneous fistula (following laryngectomy)

- Injury to the accessory, vagus, hypoglossal, or marginal mandibular nerves (following neck dissection), or chyle leak (following neck dissection)

- Mucositis (early complication of radiotherapy) or xerostomia (complication of radiotherapy)

- Chronic pain, persistent hoarse voice, or hearing loss (following chemoradiotherapy)

Key Points

- Head and neck cancer refers to malignancies of the oral cavity, pharynx, larynx, paranasal sinuses, nasal cavity or salivary glands

- Alcohol and tobacco use account for the majority of head and neck cancers

- Suspected cases require a biopsy of the lesion, typically followed by a staging CT scan of the neck and chest

- Management varies greatly depending on the location, size, stage, and grade of the cancer, as well as patient preference and co-morbidities