Introduction

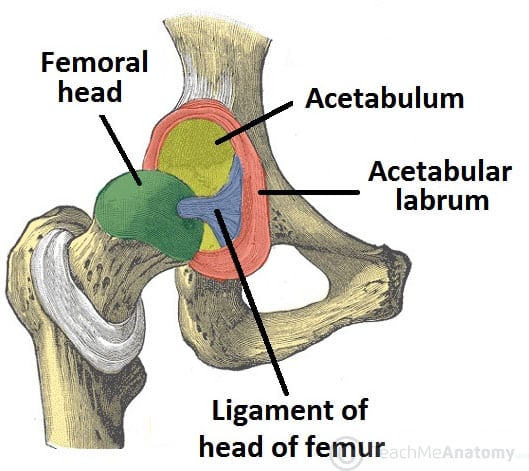

The acetabulum is a cup-like depression located on the inferolateral aspect of the pelvis, formed by the ilium, ischium, and pubic bones. It articulates with the head of the femur to form the hip joint.

Structurally, the acetabulum is considered to have two distinct columns (1) anterior column extending from the anterior iliac spines to the pubic rami (2) posterior column extending from the sciatic notch to the ischium. Together, they form an inverted Y shape with the acetabulum in the centre.

An acetabular fracture usually follows a high-energy injury, such as a road traffic collision or a significant fall from height (although in the elderly or in those with poor bone health, this may be following low energy mechanisms).

Acetabular fractures are important fractures to identify early, and whilst some can be treated conservatively, they often can be complex and require specialist input in their definitive treatment

Figure 1 – The articulating surfaces of the hip joint, with the acetabulum and head of the femur

Clinical Features

Patients will present with significant pain and swelling following the initial injury, with an inability to weight bear. Associated injuries* are common with pelvic fractures (including associated hip dislocations or femoral neck fractures), therefore a thorough secondary survey is essential.

Check (and document) the neurovascular status of both limbs during the assessment. Check for any evidence of open fracture and assess the condition of the overlying skin for any Morel-Lavallée lesions.

*Fortunately associated abdominal and urethral injuries are rare (unlike in pelvic ring fractures)

Morel Lavallée Lesion

A Morel-Lavallée lesion is an internal degloving injury, whereby the skin and subcutaneous tissues are abruptly separated from the underlying fascia due to trauma.

A potential space is produced superficial to the fascia that is then filled with fluid. The resulting collection may spontaneously resolve or become encapsulated and persistent.

Figure 2 – A CT scan showing a Morel-Lavallée lesion (arrows) around the left ilium following high-energy trauma

Investigation

Any patient presenting following a high-energy injury with suspected acetabular fracture must be assessed and managed as per ATLS guidelines.

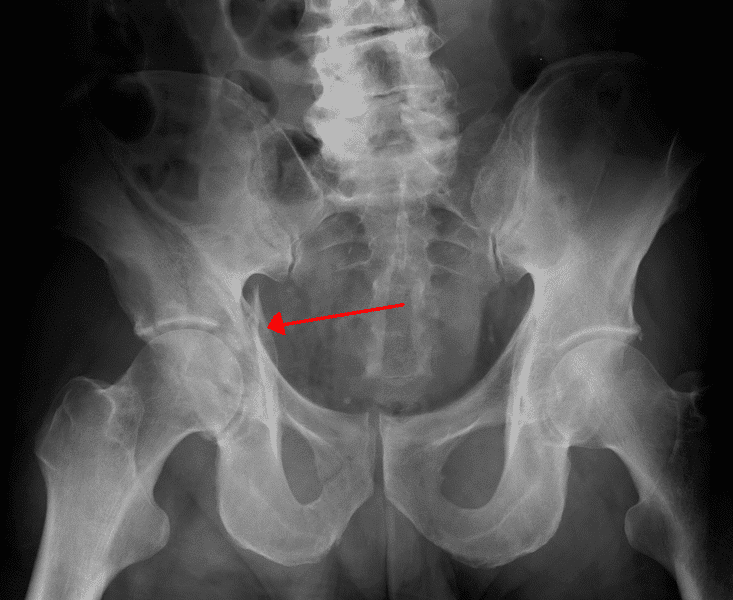

Plain film radiographs should initially be performed in suspected cases of acetabular fractures, with antero-posterior view (Fig. 3), Judet view (obtained by tilting the patient 45o laterally in both directions), with the obturator oblique view visualising the anterior column and the posterior wall, and the iliac oblique view visualising the anterior wall and posterior column.

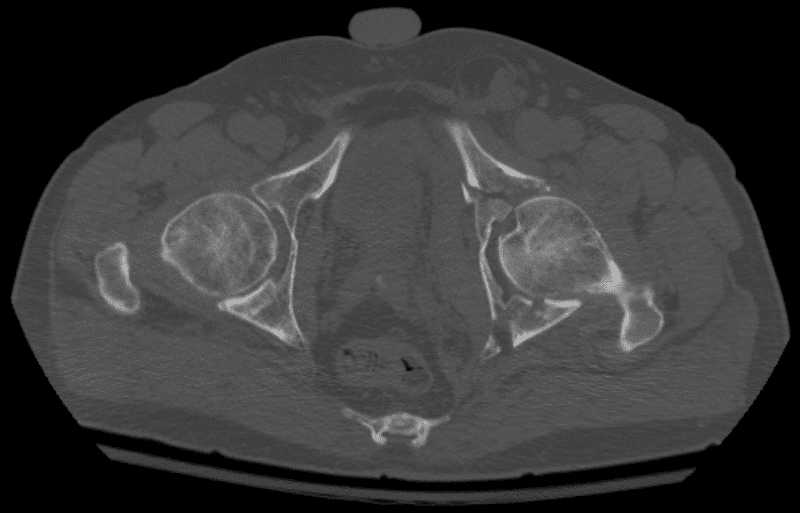

However, in the trauma setting, often a CT scan is performed as part of the patient assessment, which usually negates the need for plain films, and is considered the gold-standard for acetabular fracture diagnosis.

Figure 3 – An acetabular fracture (arrow) as seen on plain film radiograph in AP view

Classification

The Judet and Letournel classification for acetabular fractures groups acetabular fractures into two groups, either elementary fractures or associated fractures:

- Elementary = posterior wall, posterior column, anterior wall, anterior column, transverse

- Associated = posterior wall + posterior column, transverse + posterior wall, T-type, anterior column + posterior hemitransverse, both columns

Management

Initial management of a patient with high energy trauma follows the ATLS guidelines and should always begin with a primary survey to identify life-threatening injuries

In contrast to pelvic ring injuries, major haemorrhage is unusual and a pelvic binder is not indicated (except in cases of combined pelvic and acetabular fractures). Any associated hip dislocation should be reduced urgently if there is significant joint incongruity, to help minimise further damage to the acetabulum.

Undisplaced or minimally displaced acetabular fractures can be managed conservatively with protected weight bearing for 6-8 weeks.

Figure 4 – Axial view CT scan of a left complex comminuted acetabular fracture, involving both anterior and posterior columns

Surgical Management

In young patients with displaced fractures, surgery is usually performed to restore the anatomy of the joint surface and pelvic stability. In more elderly patients, fracture fixation may be performed as a precursor to total hip replacement, performed either as a single-stage or a two-stage procedure.

There are many surgical approaches to the acetabulum, the choice which is determined by the fracture pattern. As a general rule, anterior approaches are used for fractures with more anterior displacement and posterior approaches (such as Kocher-Langenbeck) are used for fractures with more posterior displacement.

Complications

Complications following acetabular fractures include secondary osteoarthritis and venous thromboembolism. Nerve injury, mainly to the sciatic or obturator nerves, is fortunately less common.

Key Points

- An acetabular fracture usually occurs from a high-energy injury

- The gold standard to their diagnosis is with CT imaging

- Undisplaced or minimally displaced acetabular fractures can be managed conservatively, whilst in young patients with displaced fractures, surgery is usually required