Introduction

The term bowel obstruction refers to a mechanical blockage of the bowel, whereby a structural pathology physically blocks the passage of intestinal contents. Around 15% of acute abdomen cases are found to have a bowel obstruction. Patients can have bowel obstruction affecting the small bowel, the large bowel, or both.

Once the bowel segment has become occluded, gross dilatation of the proximal limb of the bowel occurs. There becomes an increased peristalsis of the bowel, which in turn leads to secretion of large volumes of electrolyte-rich fluid into the bowel (often termed ‘third spacing’). Urgent fluid resuscitation and a careful fluid balance is required.

*When the bowel is not mechanically blocked but is adynamic and not working properly, this is typically either an ileus or pseudo-obstruction

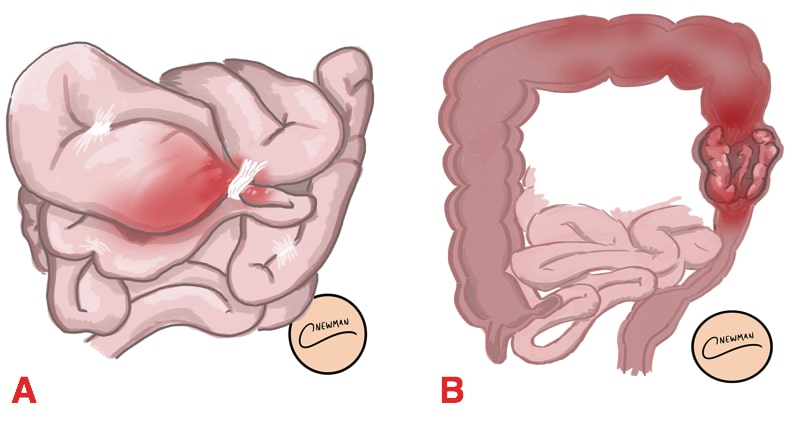

Closed Loop Obstruction

In patients with a mechanical bowel obstruction, if there is a second separate obstructing point proximally (e.g. a large bowel obstruction with a competent ileocaecal valve), this is termed closed-loop obstruction.

A closed-loop obstruction is a surgical emergency as if not corrected, the bowel will continue to distend within a closed segment of bowel, stretching the bowel wall until it becomes ischaemic and this can further lead to perforation.

Aetiology

The most common causes of bowel obstruction depend on location:

- Small bowel – adhesions or hernia

- Large bowel – malignancy, diverticular disease, or volvulus

The full list of causes of bowel obstruction can otherwise be divided into extramural, intramural, and intraluminal causes (Table 1)

|

Location |

Causes |

|

Intraluminal |

Gallstone ileus, ingested foreign body, faecal impaction |

|

Mural |

Cancer, inflammatory strictures*, intussusception**, diverticular strictures, Meckel’s diverticulum, lymphoma |

|

Extramural |

Hernias, adhesions, peritoneal metastasis, volvulus |

Table 1 – Causes of bowel obstruction *especially in Crohn’s patients **most common in children

Clinical Features

Patients with bowel obstruction will present with the cardinal features of bowel obstruction (to varying degrees):

- Abdominal pain – colicky or cramping in nature (secondary to the bowel peristalsis)

- Vomiting – occurring early in proximal obstruction and late in distal obstruction

- Abdominal distension

- Absolute constipation – occurring early in distal obstruction and late in proximal obstruction

On examination, patients may show evidence of the underlying cause (e.g. surgical scars, cachexia from malignancy, or obvious hernia) or abdominal distension. Ensure to assess the patient’s fluid status, as significant third-spacing can occur in bowel obstruction.

Palpate for focal tenderness* (including guarding and rebound tenderness on palpation). Percussion may give a tympanic sound and auscultation may reveal ‘tinkling’ bowel sounds, both signs characteristic of bowel obstruction.

*Patients with bowel obstruction may have abdominal tenderness, however should not have features of guarding or rebound tenderness, unless ischaemia is developing

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnoses for a patient presenting with suspected bowel obstruction include pseudo-obstruction, paralytic ileus, toxic megacolon, or constipation

Investigations

Laboratory tests

All patients with suspected bowel obstruction require routine urgent bloods on admission, as well as a Group and Save (G&S). Ensure to closely monitor renal function and electrolytes closely, given the risk of third-spacing.

A venous blood gas can be useful to evaluate for end-organ and for the immediate assessment of any metabolic derangement (secondary to dehydration or excessive vomiting).

Imaging

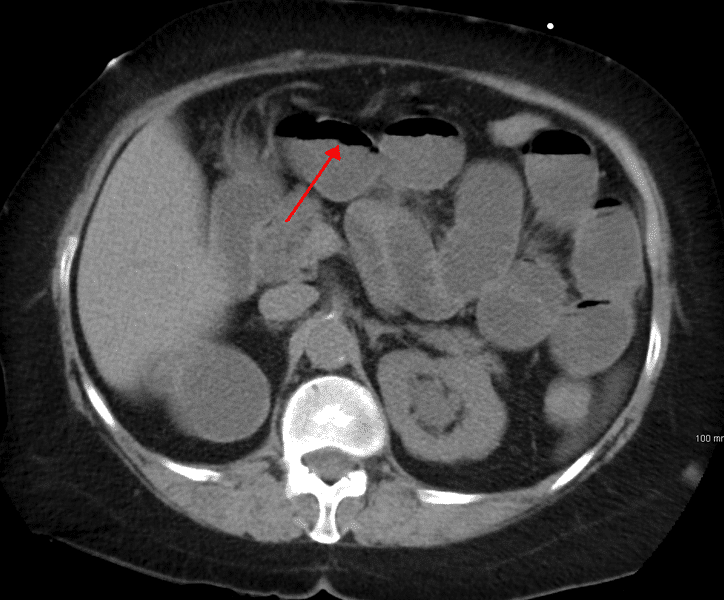

A CT scan with intravenous contrast of the abdomen and pelvis (Fig. 2) is the imaging modality of choice in suspected bowel obstruction. This will not only confirm the presence of bowel obstruction (versus a pseudo-obstruction or paralytic ileus), but also demonstrate the underlying cause.

Figure 2 – CT scan demonstrating features of small bowel obstruction

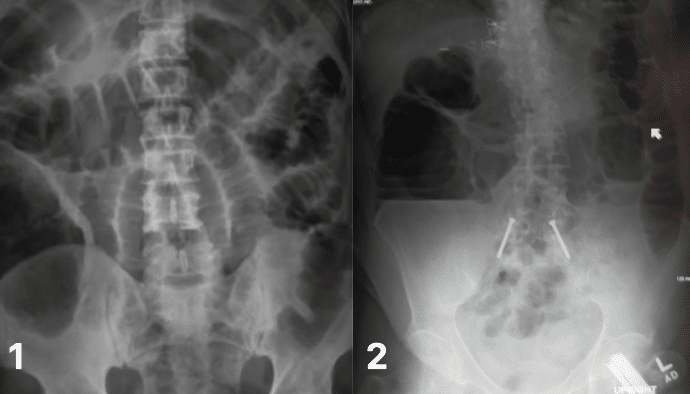

A plain abdominal radiograph (AXR) is still used in some settings as the initial investigation for bowel obstruction. The AXR findings (Fig. 3) seen in a patient with bowel obstruction are:

- Small bowel obstruction – Dilated bowel (>3cm), central abdominal location, and valvulae conniventes visible (lines completely crossing the bowel)

- Large bowel obstruction – Dilated bowel (>6cm, or >9cm if at the caecum), peripheral location, and haustral lines visible (lines not completely crossing the bowel, ‘indents that go Halfway are Haustra’)

Management

The definitive management of bowel obstruction is dependent on the aetiology and the presence of any specific complications, such as bowel ischaemia or perforation.

These patients are often intravascularly fluid deplete and need urgent fluid resuscitation, with careful attention paid to fluid balance (often several litres of intravenous fluid may be required in the first 24 hours).

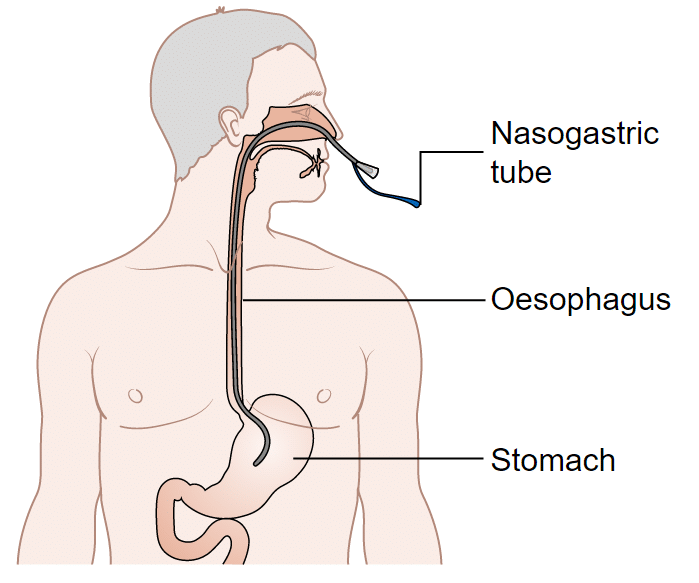

All patients with bowel obstruction should have a nasogastric tube (NG tube) inserted and most will require a urinary catheter

Patients with closed loop bowel obstruction or evidence of bowel ischaemia will require urgent surgery.

Conservative Management

In the absence of signs of ischaemia or perforation, initial management for cases of adhesional bowel obstruction is conservative (with a success rate of around 80%), often referred to as a “drip and suck” management:

- Make the patient nil-by-mouth (NBM) and insert a nasogastric tube (Fig. 4) to decompress the bowel (“suck”)

- Start intravenous fluids and correct any electrolyte disturbances (“drip”)

- Urinary catheter and fluid balance

- Analgesia as required with suitable anti-emetics

Figure 4 – A nasogastric tube should be inserted as part of management of bowel obstruction

A water soluble contrast study can be performed in cases that do not resolve initially with conservative management. An AXR after around 6hrs since oral contrast* given can check to see evidence of ongoing obstruction versus resolution (if contrast passes distally to the obstruction, this is a good prognostic sign)

*Gastrograffin (a common oral contrast medium used for these studies) may have therapeutic properties in resolving obstruction, due to its osmotic effect on bowel wall oedema, however evidence for this remains equivocal

Surgical Management

Surgical intervention is indicated in patients with:

- Suspicion of intestinal ischaemia or closed loop bowel obstruction

- A cause that requires surgical correction (such as a strangulated hernia or obstructing tumour)

- If patients fail to improve with conservative measures (typically after ≥48 hours)

The nature of surgical management will depend on the underlying cause but generally will warrant a laparotomy. If resection of bowel is required, the re-joining of obstructed bowel is often not possible and therefore a defunctioning stoma may be necessary.

Complications

The complications of bowel obstruction include bowel ischaemia or bowel perforation leading to faecal peritonitis (high mortality).

Patients in bowel obstruction can often be severely intravascularly fluid deplete, resulting in acute kidney injury and other end-organ injury if mismanaged.

Key Points

- Small bowel obstruction is commonly caused by adhesions or hernia, and large bowel obstruction is commonly caused by malignancy or diverticular disease

- The cardinal features for bowel obstruction are abdominal pain, vomiting, abdominal distension, and absolute constipation

- Early recognition of those patients with impending strangulation and ischaemia is essential, as urgent surgery will be required in such cases

- The majority of cases of adhesional bowel obstruction can be managed with a “drip and suck” approach