Introduction

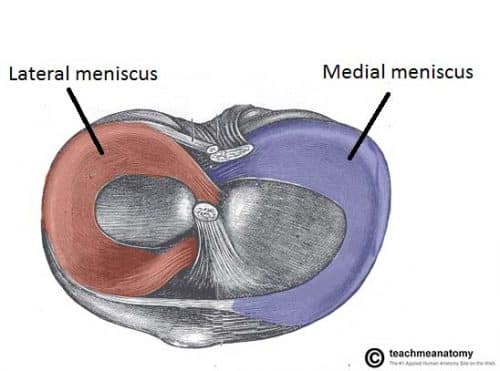

Meniscal tears refer to damage of the menisci (the C-shaped fibrocartilage found in the knee joint). The menisci rest on the tibial plateau and have two main functions (1) shock-absorbers of the knee joint (2) increase articulating surface area.

The medial meniscus is less circular than the lateral and is attached to the medial collateral ligament, whilst the lateral meniscus is not attached to the lateral collateral ligament.

In this article, we shall look at the classification, clinical features and management of meniscal tears.

Pathophysiology

The most common causes for meniscal tears are trauma-related injury and degenerative disease (the latter more common in older patients).

In traumatic tears, the mechanism typically involves a young patient who has twisted their knee whilst it is flexed and weight-bearing, with the onset of symptoms following soon after.

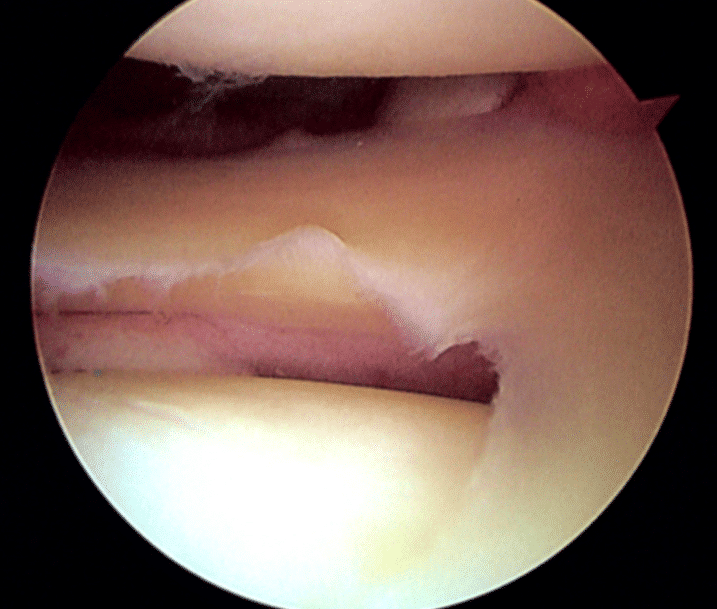

Figure 2 – Types of meniscal tears

There are a number of types of meniscal tears. The most common type of tear is a longitudinal tear – often termed a ‘bucket-handle’ tear – whereby the central tear becomes separated from the lateral fragment.

- Vertical

- Longitudinal(Bucket-Handle)

- Transverse(Parrot-Beak)

- Degenerative

Clinical Features

Patients often report a ‘tearing’ sensation in their knee, associated with an intense sudden-onset pain. The knee invariably swells slowly subsequently over a period of 6-12 hours.

In cases where the meniscal tear results in a free body within the knee (typically the bucket-handle type), it may be locked in flexion and unable to extend.

On examination, there is a joint line tenderness, significant joint effusion, and limited knee flexion. Specific tests to identify a meniscal tear include McMurray’s Test* and Apley’s Grind Test* (although in the acutely swollen knee, they can often prove difficult).

*These tests can often prove very painful to the patient so many clinicians no longer advocate their use

Differential Diagnoses

The differential diagnoses for an acutely swollen knee joint following trauma include fracture, cruciate ligament tear, collateral ligament tear, and osteochondritis dissecans.

Investigations

Plain film radiographs of the affected knee are often performed in the initial assessment to exclude a fracture

An MRI scan is the gold-standard investigation to confirm a meniscal tear, useful to also attempt to identify the type of tear.

Management

The immediate management of an acutely swollen knee is for rest and elevation with compression and ice. Most small (<1cm) meniscal tears will initially swell however the pain will subside over the next few days as the tear heals.

For larger tears or those remaining symptomatic, arthroscopic surgery is indicated:

- If the tear is in the outer third of the meniscus (where it has a rich vascular supply), then the tear can often be repaired using sutures

- If the tear is in the inner third, then the tear is usually trimmed to reduce locking symptoms (and middle third tears may either be repaired or trimmed)

Complications

A meniscal tear is a risk factor for developing secondary osteoarthritis.

Knee arthroscopy carries a risk of deep vein thrombosis and damage to local structures, such as the saphenous nerve and vein, the peroneal nerve, and the popliteal vessels.

Key Points

- Meniscal tears are caused due to either trauma or as degenerative disease

- Presents with a ‘tearing’ sensation in their knee, sudden-onset pain, swelling, and sometimes locked in flexion

- Gold standard diagnosis is through MRI scanning

- Smaller tears can be managed conservatively, however for larger tears or those remaining symptomatic, arthroscopic surgery is indicated