Introduction

A limp is any asymmetric gait that deviates from a normal age-appropriate pattern.

An acute limp in a child is a common presentation to both primary and secondary care and can be due to a wide variety of causes. In most children, a limp is caused by a mild self-limiting issue, such as a strain or sprain, however there are less common but serious causes that must be identified.

Differential diagnoses can be categorised by age group, yet many of these conditions can occur at any age. As with all interactions with children, it is important to always consider the possibility of non-accidental injury.

Clinical Assessment

In a child presenting with a limp, ensure to ask details regarding the onset, progression, and any exacerbating and relieving factors for the limp.

Concurrent symptoms, such as fevers, night sweats, weight loss, or abnormal rashes, should be clarified. In young children, ascertain the birth history (e.g. breech delivery) and attainment of developmental milestones. Always check for Red Flag features

Examination should be of the whole child, not just the affected joint(s), including checking the child’s observations, height, and weight, and compare to previous if able.

The pGALS assessment (paediatric Gait, Arms, Legs, Spine) assessment is a useful musculoskeletal screening examination that can help give an overall assessment of the child, before performing a more focussed examination of the affected joint(s).

Examination of the specific joint involved typically follows the “look, feel, move” approach of orthopaedic examinations. The special tests to perform will depend on the joint being examined and clinical judgement as to potential differential diagnoses

Red Flag Features for a Limping Child

- Pain waking the child at night (potential malignancy)

- Any redness, swelling, or stiffness in the joint or limb (potential infection or inflammatory joint disease)

- Presence of weight loss, anorexia, fevers, night sweats, or fatigue (potential malignancy, infection, or inflammatory joint disease)

- Unexplained rash or bruising (potential non-accidental injury)

- Unable to bear weight or painful limitation of range of motion (potential trauma or infection)

Investigations

Investigation choice will depend on the main differentials

For those with concerning or red flag features, blood tests should be performed, including FBC, CRP, and ESR. Plain film radiographs can will aid in diagnosis, often requiring multiple views (e.g. antero-posterior, lateral, and frog-leg views for the hip joint)

Further investigations will depend on the suspected underlying cause

Figure 2 – A normal plain film radiograph of a child’s ankle joint

Differential Diagnoses

There is a wide range of differentials for the limping child, however as a general guide, these can be categorised broadly depending on the age group:

- Less than 3 years = developmental dysplasia of the hip

- 3yrs – 10yrs old = transient synovitis or Perthes’ disease

- 10yrs – 18yrs old = slipped upper femoral epiphysis, Osgood-Schlatter disease, Osteochondritis dissecans, Chondromalacia patellae

- All ages = fracture or soft tissue injury, osteomyelitis, septic arthritis, malignancy (e.g. primary bone cancers), juvenile idiopathic arthritis

Less common causes for the limping child includes non-malignant haematological disease (e.g. sickle cell disease), metabolic disease (e.g. Rickets), neuromuscular disease (e.g. cerebral palsy), or a primary anatomical abnormality (e.g. limb length discrepancy)

Specific Conditions

Developmental Dysplasia of the Hip

Developmental Dysplasia of the Hip (DDH) is an abnormal development of the hip, resulting in an acetabulum that is too shallow to hold the femoral head in place, resulting in recurrent subluxation and dislocation of the hip joint.

Risk factors for the condition include female gender, first-born children, those delivered breech presentation, oligohydramnios, and macrosomia.

Presentation will vary depending on age, however screening tests (such as Barlow or Ortolani tests) can be done at birth to identify those at high risk.

Clinical Tests for Developmental Dysplasia of the Hip

- Galeazzi – tests for apparent leg length discrepancy due to a unilateral dislocated hip

- Barlow – aims to dislocate an unstable hip by adduction and depression

- Ortolani – aims to relocate a dislocated hip by elevation and abduction

Those determined at high risk can then undergo a screening ultrasound imaging, which identifies most cases at 6 weeks. Plain film radiographs become the imaging of choice in older children (who may have been missed from screening), due to ossification of the femoral head.

Management depends on age and stability of the hip. Intervention options include bracing with a Pavlik harness, closed reduction and spica casting, or open reduction and surgical osteotomy.

Transient Synovitis

Figure 4 – Ultrasound scan showing transient synovitis of the hip joint

Transient Synovitis is a temporary inflammation of the synovium of a joint. It commonly occurs in the presence of a concurrent viral upper respiratory tract infection, however can occur at any time.

It is the most common cause of hip pain in children, however should be views as a diagnosis of exclusion; importantly, it must be differentiated from septic arthritis – the Kocher criteria can be useful in such scenarios

Management is conservative, with the child being provided simple analgesia. It usually resolves spontaneously within 7–10 days from onset.

Kocher Criteria

The Kocher Criteria is a useful tool to aid in the differentiation of transient synovitis and septic arthritis. The likelihood of septic arthritis increases with the total score: 1 = 3%, 2 = 40%, 3 = 95%, 4 = 99%

The four prognostic criteria include

- Fever >38.5 C

- Non-weight bearing on the affected limb

- WBC >12×10^9/L

- ESR >40mm/hr (or CRP >20 mg/L)

Perthes Disease

Perthes Disease describes an idiopathic avascular necrosis (AVN) occurring to the upper femoral epiphysis, resulting in bone loss and structural collapse. It most commonly occurs in those aged 4-8 years old, and is five times more common in males.

It typically presents as an atraumatic progressive pain affecting the hip or knee (bilateral in around 15% of patients), with a concurrent limp. Clinical examination will demonstrate a stiff hip with globally reduced movements, especially abduction and internal rotation.

Plain film radiographs are first line imaging for the condition, which may show joint space widening in early disease, or collapse and deformity of the femoral head in late disease.

Management is complicated and depends on age and severity of disease; the mainstay of management in early disease includes rest and analgesia. Regular surveillance is needed, as can in some cases progress to requiring femoral (or pelvic) osteotomies.

Outcomes are better in younger patients, due to the better ability in remodelling.

Figure 5 – Plain film radiograph demonstrating left Perthes disease

Slipped Upper Femoral Epiphysis

Slipped Upper Femoral Epiphysis (SUFE) is a common disorder affecting adolescents, whereby there is a displacement of the metaphysis relative the epiphysis, resulting in it lying postero-inferior to the metaphysis (A SUFE can be classified as a Type 1 Salter-Harris growth plate injury).

It is most common in patients in periods of rapid growth (i.e. 10-16yrs old), especially in overweight or males, and up to 20% cases occurring bilaterally. It presents with atraumatic progressive pain affecting the hip or knee. On examination, there is a reduction in the range of motion in internal rotation, flexion, and abduction*.

On plain film radiograph, Trethowan’s sign is classically present (Fig. 6), where an imaginary line drawn up the lateral edge of the femoral neck (line of Klein) fails to intersect the epiphysis.

Treatment is usually percutaneous pin fixation, and patients at high risk of a contralateral slip will be considered for prophylactic fixation. If left untreated, SUFE may progress to avascular necrosis or malunion of the affected joint.

*Drehmann sign is positive in cases of SUFE, whereby there external rotation of the joint with passive hip flexion

Figure 6 – Plain film radiograph demonstrating a left slipped upper femoral epiphysis

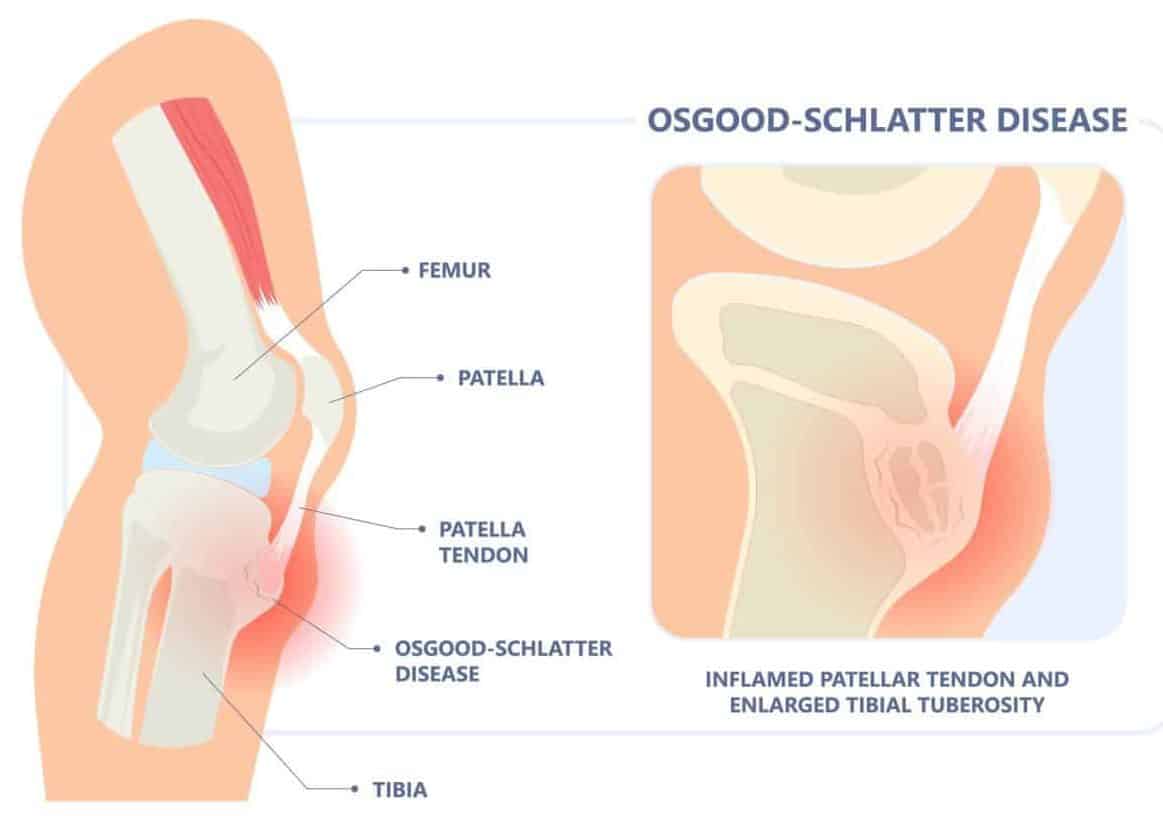

Osgood-Schlatter’s Disease

Osgood-Schlatter’s Disease is caused by repetitive microtrauma at the insertion of the patellar tendon into the proximal tibia, resulting in a traction apophysitis of the tibial tuberosity.

The condition usually affects males aged 10-15yrs and presents with anterior knee pain, which is exacerbated by strenuous activity and kneeling. On examination, there is often a tender enlarged tibial tuberosity.

Lateral plain film radiograph of the knee will show an irregularity and fragmentation of the tibial tuberosity. Treatment is often simple analgesia and activity modification in the majority of cases.

Figure 7 – Illustration demonstrating the pathophysiology of Figure – Illustration demonstrating the pathophysiology of Osgood-Schlatter’s disease

Key Points

- The limping child is a common presentation, with a wide range of differentials

- Most differentials can be categorised based on the child’s age

- Red flag features include pain at night, fevers or night sweats, unexplained rash or bruising, and unable to bear weight