Biceps Tendinopathy

Introduction

Tendinopathy is a broad term used to encompass a variety of pathological changes that occur in tendons, typically due to overuse. This results in a painful, swollen, and structurally weaker tendon that is at risk of rupture*.

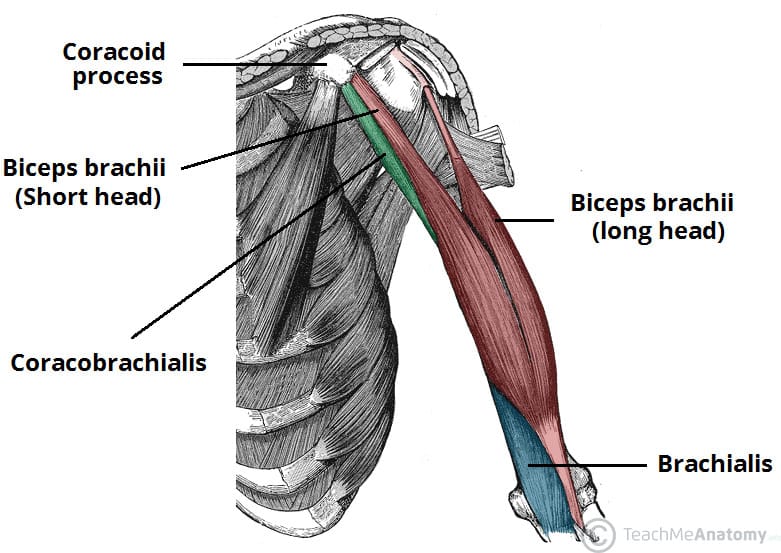

Biceps tendinopathy can occur in both the proximal and distal bicep tendons. It is common in younger individuals who are active (e.g. sports with repetitive flexion movements, such as tennis or cricket) and in older individuals with more of a degenerative tendinopathy.

The majority of this article will focus on distal biceps tendinopathy.

*The tendons become disorganised, hypervascular, and degenerative; whilst inflammation is certainly present, it is not thought to be the primarily pathological process

Clinical Features

Patients will present with pain, made worse with stressing the tendon (and alleviated through rest and ice therapy). This can also be associated with weakness (flexion and supination) and stiffness.

On examination, patients will demonstrate tenderness over the affected tendon. If the patients has avoided using the limb due to pain, there may be a loss of muscle bulk due to disuse atrophy.

There are certain special tests that can be performed specifically for biceps tendinopathy:

- Speed test (proximal biceps tendon) – The patient stands with their elbows extended and their forearms supinated. They then forward flex their shoulders against the examiners resistance

- Yergason’s test (distal biceps tendon) – The patients stands with their elbows flexed to 90 degrees and their forearm pronated. They actively supinate against the examiners resistance

Differential Diagnoses

The main differential diagnoses* to consider in a patient with suspected biceps tendinopathy include inflammatory arthropathy, radiculopathy, osteoarthritis, or rotator cuff disease (for proximal tendon involvement)

*Biceps tendinopathy is rarely an isolated pathology and often the differentials may be co-existing, hence the need for thorough history and examination

Investigations

The diagnosis of bicep tendinopathy is largely clinical, with further investigations reserved for cases where there is diagnostic uncertainty.

Blood tests (FBC and CRP) and plain film radiographs can be undertaken as first line investigations, often most useful to exclude other differentials.

Specialist imaging is rarely warranted, but ultrasound imaging can identify involved thickened tendons and MRI imaging can show thickened inflamed tendons.

Management

Nearly all cases can be treated conservatively, with the use of analgesia (specifically NSAIDs, if tolerated) and ice therapy as first line. Physiotherapy also plays an important role.

Ultrasound-guided steroid injections can be useful in cases unresponsive to initial conservative management.

Rarely, surgical options are required in refractory cases. Arthroscopic tenodesis (tendon is severed and reattached) or tenotomy (division of the tendon) for decompression are options that may be discussed with the patient if indicated.

Prognosis

Most cases will recover well with no complications. Small proportion of cases may develop recurrent or chronic pain at the affected site or some weakness.

Chronic cases are at an increased risk of having a biceps tendon rupture.

Biceps Tendon Rupture

Rupture of the distal biceps tendon is an uncommon injury. It can be classified as either complete (through entire tendon) or partial (remains partly intact) tears. These injuries typically occur following sudden forced extension of a flexed elbow.

Those with previous episodes of biceps tendinopathy are at increased risk. Other risk factors for biceps tendon rupture include steroid use, smoking, chronic kidney disease (CKD), or use of fluoroquinolone antibiotics.

Clinical Features

Patients will present with sudden onset pain and weakness* at the affected area. Patients often report the feeling of a “pop” during the incident.

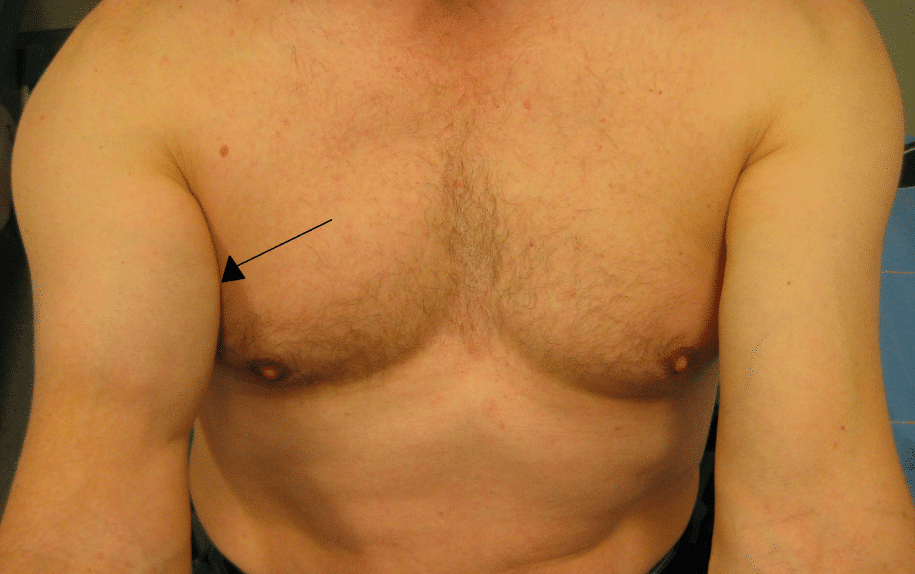

Examination demonstrates marked swelling and bruising in the antecubital fossa. As the proximal muscle belly retracts (due to loss of counter traction) a bulge may become evident in the arm; this is termed the “reverse Popeye sign” (Fig. 2).

The Hook test is a special test to identify a potential distal tendon rupture:

- The elbow is actively flexed to 90º and fully supinated, the examiner attempts to ‘hook’ their index finger underneath the lateral edge of the biceps tendon (which cannot be done in a ruptured biceps tendon)

*Action of the brachialis and supinator muscles allows for flexion at the elbow to remain.

Figure 2 – A right distal biceps tendon rupture

Investigations

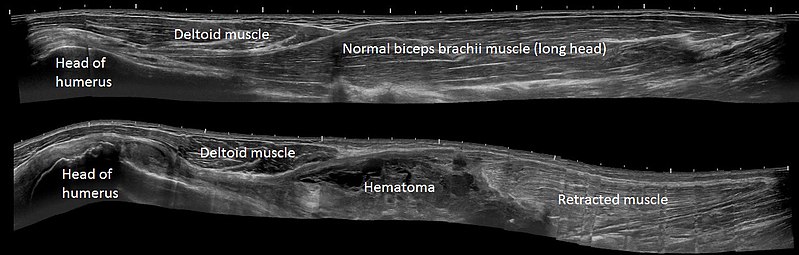

Whilst cases can be diagnosed clinically, confirmation is usually obtained via ultrasound imaging. This also helps the surgeon localise the distal end of the biceps tendon, which can retract many inches proximally.

If ultrasound imaging is inconclusive but clinical suspicion remains, an MRI scan may be warranted to further assess.

Figure 3 – Ultrasound scan of a normal biceps tendon (above) and of a biceps tendon rupture (below)

Management

Discussions with the patient regarding the best management option for them in cases of biceps tendon rupture are essential.

As elbow flexion and supination can still occur (albeit weakened), due to the remaining action of other associated muscles, not all cases require surgical management. However, this does come with issues with fatiguability and weakness.

Accordingly, for lower demand patients, a conservative approach may be most suitable. Analgesia and physiotherapy form the mainstay of conservative management, often allowing for significant recovery of muscle strength and function.

Operative Management

For those who warrant surgical management, either an anterior single-incision or a dual incision technique* will be required. The operation involves forming a bone tunnel in the radius and re-inserting the ruptured tendon end.

Surgical repair should occur within a few weeks of initial injury, otherwise the tendon will retract and scar; in missed cases, reconstruction with tendon allograft is therefore often required.

The main complications from surgery are injury to lateral antebrachial cutaneous nerve, posterior interosseous nerve, or radial nerve (rare).

*The anterior single incision involves a single incision in the antecubital fossa, whilst the dual incision technique involves a smaller anterior incision in the antecubital fossa and a posterolateral elbow incision (between the ECU and EDC).

Key Points

- Biceps tendinopathy will present with pain (made worse with stressing the tendon), weakness, and localised tenderness

- Most cases of tendinopathy will be treated conservatively with analgesia and physiotherapy

- Rupture of the distal biceps can be diagnosed clinically, with ultrasound imaging for confirmation and to aid potential surgical intervention

- Both conservative and surgical management options are possible for rupture of the distal biceps