Introduction

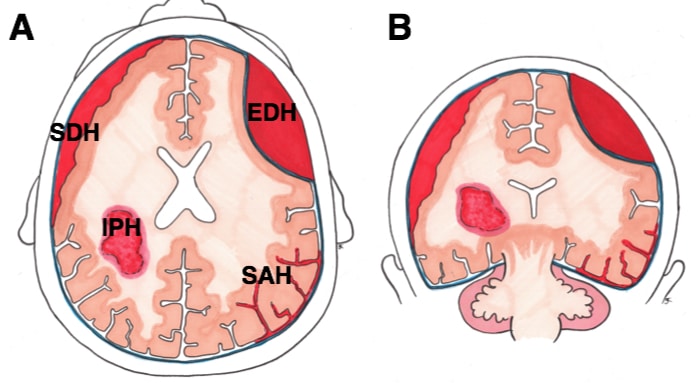

An intracerebral haemorrhage (ICH), or haemorrhagic stroke (or intraparenchymal haemorrhage), is a type of bleed which occurs within the brain parenchyma. It is the second most common form of stroke, representing 10-15 % of all strokes, and often results in significant morbidity and mortality.

Depending on the aetiology of the haemorrhage, ICH can be classified as primary or secondary. Primary ICH occurs spontaneously, whilst secondary ICH results from underlying lesions; common aetiologies of primary and secondary ICH include:

- Primary

- Hypertension

- Cerebral amyloid angiopathy

- Secondary

- Trauma

- Primary and secondary brain tumours

- Arteriovenous malformation (AVM)

- Intracranial aneurysms

- Coagulation or clotting disorders

- Haemorrhagic conversion of ischaemic infarcts

Risk Factors

Common risk factors for primary ICH include increasing age, male sex, Asian ethnicity, excessive alcohol consumption, smoking, illicit drug use (such as cocaine, amphetamines), and anti-coagulation or anti-platelet drug therapy.

Clinical Features

Neurological symptoms in ICH have a gradual onset occurring over minutes to hours.

The clinical presentation of ICH varies according to the size and the location of the haematoma (see Oxford Stroke Classification), however symptoms can often include nausea and vomiting, loss of sensory or motor function, severe headache, and alterations in level of consciousness.

- Haemorrhages occurring in the basal ganglia causes contralateral hemiparesis/ hemiplegia, whereas a thalamic haemorrhage presents with contralateral hemisensory loss

- Cerebellar haemorrhages often results in the classical cerebellar signs (D-dysdiadochokinesia, A- ataxia, N- nystagmus, I- intentional tremor, S-slurred speech, H-hypotonia)

- They may also present with signs of raised ICP as a result of hydrocephalus from compression of the 4th ventricle or extension of blood into the ventricular system

- Lobar haemorrhages present with focal signs and symptoms depending on the cortical area involved. These can include hemiparesis, hemisensory deficits, dysphasia and visual field deficits.

Common Locations

Spontaneous ICH commonly happens at the following locations: basal ganglia (most common), thalamus, pons, cerebellum. If there is intraventricular extension of the ICH, this is an independent risk factor for a worse outcome.

Investigations

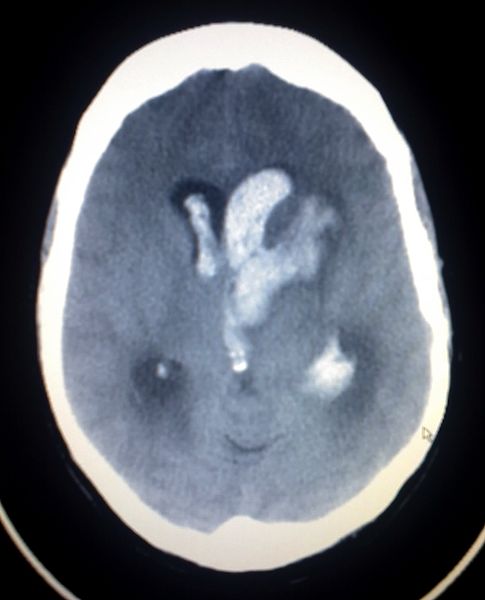

An urgent non-contrast CT head is the gold standard imaging modality used in the diagnosis of ICH (Fig. 2). They are quick, sensitive, and useful in demonstrating acute bleeds, interventricular extension, hydrocephalus and signs of mass effect.

MRI head imaging is less frequently used as a first line investigation for ICH, however they may be used to identify the underlying causes, such as tumours or vascular malformations.

If aneurysms or AVMs are suspected, cerebral angiography, such as CT angiography or digital subtraction angiography, is indicated to determine the nature of the vascular lesion and localise the source of the bleed.

Management

ICH is a medical emergency, requiring urgent therapy. Initial management of ICH focuses on stabilising the patient as per ATLS guidelines and preventing secondary brain injury.

Blood pressure control plays an important role in its management. Blood pressure lowering depends upon several factors including current systolic BP, aetiology of bleed, patient prognosis and if any surgery is planned.

Patients on anticoagulation or antiplatelet therapy should have their coagulopathy reversed through the administration of an appropriate reversal agent. In some cases, discussion with the haematology team may be required.

Some patients may experiences seizures related to the ICH. These are treated with anti-epileptic drugs; in some patients, prophylactic anti-epileptic drugs may be started to reduce the seizure risk.

Surgical Management

Not all patients will undergo surgery. The decision to operate depends upon a number of factors including the patient’s neurological condition, the patients age and functional status, and the size and location of the haematoma.

The role of surgery in the management of supratentorial ICH remain controversial. One large randomised prospective study found there was no overall benefit of early haematoma evacuation in patients with a supratentorial ICH when compared to conservative management.

However, in patients with a cerebellar ICH, surgery is often indicated due to the close proximity to vital structures and the propensity for the haematoma to cause brainstem compression. This typically is in the form of a posterior fossa decompression.

Patients requiring surgery will often undergo a craniotomy (removal of bone with replacement) or craniectomy (removal of bone without replacement) and evacuation of the haematoma. Some patients may require the insertion of an ICP monitor device for ongoing monitoring.

Prognosis

The prognosis of ICH is often poor, with a 30-day mortality rate of 20%-60%. Prognostic factors include GCS at presentation, haematoma volume and location, age, anti-coagulant use and presence of interventricular extension.

Key Points

- Intracerebral haemorrhage is a type of bleed which occurs within the brain parenchyma

- Intracerebral haemorrhage can be classified as primary or secondary depending upon the aetiology

- Symptoms of intracerebral haemorrhage vary according to the location of haematoma

- Non-contrast CT head is the gold standard imaging modality for intracerebral haemorrhage

- The prognosis of intracerebral haemorrhage is often poor, but several factors play a role in the outcome