Introduction

The immunology of transplantation surrounds the host’s recognition and response to foreign tissue.

Following transplantation, major histocompatibility complex (MHC) antigens (termed human leukocyte antigens, or HLAs, in humans) from the donor tissue are presented to recipient T cells, leading to recipient T-cell activation.

The activation of the recipient immune system can lead to damage of the transplanted organ, through both antibody-mediated (via B-cells, activated by CD4+ T-cells, produce donor specific antibodies) or cellular-mediated (via cytotoxic T cells, natural killer cells, macrophages and neutrophils) mechanisms.

Consequently, post-transplant immunosuppression aims to modify these responses to reduce the damage occurring to the transplanted organ by the recipient’s immune system.

Tissue Typing

Prior to transplantation, HLA tissue typing is performed in potential recipients prior to listing to reduce risk of rejection. Patients are typed for class-I (HLA-A, B, and C) and class-II (HLA-DR, DQ and DP) HLA antigens.

Since each person has two chromosomes, and the paternal and maternal chromosome produce different HLA molecules, an individual has the potential to express up to six class-I and six class-II molecules.

HLA matching prior to organ allocation has the role to identify the best match between the donor organ and recipient, as this will ensure an optimal outcome and minimise the risk of rejection.

Organ Rejection

Broadly, the recipient response to the donor organ can be classified as hyperacute rejection, acute rejection, or chronic rejection. Presentation varies between the transplanted organ involved, yet diagnosis will require a tissue biopsy for definitive confirmation.

Hyperacute rejection occurs due to preformed cytotoxic antibodies directed against donor HLA or ABO antigens. There is often graft destruction within 24 hours, especially if left untreated. Hyperacute rejection can be avoided by pre-operative blood group and HLA matching.

Acute rejection is the most common type of rejection, occurring in up to 50% of grafts, and present within the first 6 months. It is most commonly caused by a T-cell mediated immune response* against the graft MHCs, with increased risk with previous HLA sensitising episodes (such as previous transplants or blood transfusions). Patients can be treated with high-dose steroids, with second line treatment options including plasma exchange or intravenous immunoglobulin.

Chronic rejection occurs after 6 months and will present as a progressive decline in organ function. Its aetiology is multifactorial, mechanisms including immune-mediated injury, ischaemia-reperfusion injury and immunosuppressive agents’ toxicity. Unfortunately, immunosuppressive therapies have limited effectiveness in reversing chronic rejection.

*A humoral acute rejection can also occur, although is much less common

Modern Immunosuppression

The primary goal of immunosuppression is to prevent graft rejection and minimise adverse reactions. Currently, immunosuppression regimens used are associated with rejection rates between 35%-40%, but graft loss due to rejection is uncommon (<5%).

Immunosuppressive drugs can be classified as induction therapies, maintenance therapies, and antirejection therapies. Current immunosuppression agents are given as combination therapies, with constituents depending on both patient and operative factors:

- Calcineurin inhibitors, such as cyclosporine or tacrolimus

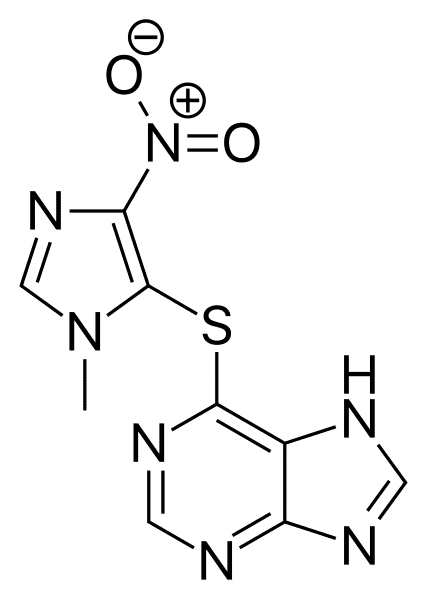

- Anti-proliferative agents, such as mycophenolate mofetil or azathioprine

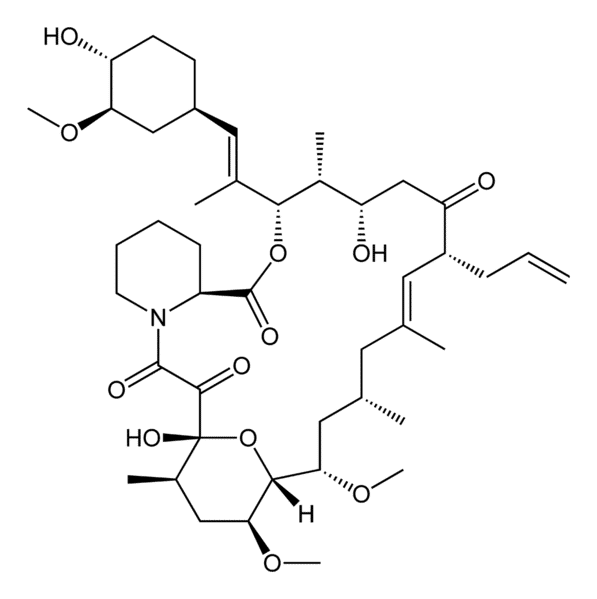

- mTOR Inhibitors, such as sirolimus and everolimus

- Corticosteroids, such as prednisolone or methylprednisolone

- Monoclonal antibodies, such as Basiliximab or Alemtuzumab

Induction Agents

Basiliximab is a monoclonal antibody that blocks IL-2 receptors, thereby inhibiting IL-2–induced T-cell activation. It is most often used as an induction agent in kidney transplantation, or as part of steroid-free protocols in pancreas transplantation. The use of Basiliximab as an induction agent allows for early steroid withdrawal and a substantial reduction in other immunosuppressive agents early after transplantation. Side effects include oedema, hypertension, and tremor.

Alemtuzumab is a monoclonal antibody directed against CD52; CD52 is widely expressed on the surface of immune cells (all B and T cells and most macrophages and natural killer cells), allowing Alemtuzumab to act as a lymphocyte-depleting agent. Its use is generally for patients with high immunological risk. Whilst effective in reducing the risk of rejection, it is also associated with a high risk of post-operative opportunistic infections and post-transplant lymphoproliferative disease.

Early Maintenance Agents

Calcineurin Inhibitors

Calcineurin inhibitors (CNIs), such as cyclosporine and tacrolimus, are strong inhibitors of the T-cell response, acting by blocking IL-2 production. They are the mainstay of most initial post-operative immunosuppression, with tacrolimus the first-line immunosuppressant in most transplant centres

They are nephrotoxic, through vasoconstrictive action, therefore their levels should be regularly monitored, and can their therapeutic windows are narrow. Other less common side effects of CNIs include hypertension, neurotoxicity (more common with tacrolimus which causes tremor, headache, irritability), diabetes mellitus, and hyperlipidaemia. Hirsutism and gingival hyperplasia are additional adverse events specific to cyclosporine.

Anti-Proliferatives

The most common anti-proliferative agents currently used are mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) and azathioprine. Neither agent requires regular therapeutic drug monitoring.

Azathioprine is a precursor of 6-mercoptourine, which in turn, once metabolised, acts to inhibit nucleotide synthesis. The most prominent side effect is severe myelosuppression, and in such cases, swapping to other anti-proliferative agents is required.

MMF is converted via first-pass metabolism into the active compound mycophenolic acid (MPA), which acts by blocking lymphocyte proliferation through inhibiting DNA formation. Its most prominent side effect is also myelosuppression.

mTOR Inhibitors

Sirolimus and everolimus are inhibitors of the Mammalian Target of Rapamycin (mTOR) and inhibit lymphocyte proliferation and differentiation.

Both agents can be used in combination with low-dose CNIs in recipients with CNI-induced nephrotoxicity, in an attempt to improve renal function without decreasing the efficacy of the immunosuppressive regimen.

They are rarely used as primary immunosuppressant and side effects include bone marrow suppression, hyperlipidaemia, peripheral oedema, and delayed wound healing.

Steroids

Corticosteroids are potent unspecific anti-inflammatory agents, are used both in induction and maintenance immunosuppression, acting on intra-cellular receptors. They are also the first line therapy for acute cellular rejection (commonly given as high-dose intravenous methylprednisolone).

Their side effects are numerous* when taken long term, including diabetes mellitus, hypertension, increased infections, osteoporosis, hyperlipidaemia, delayed wound healing, and neuropsychiatric symptoms.

*Steroid withdrawal protocols (MPA plus CNI) are currently used to reduce the long-term complications associated with corticosteroids

Long-Term Maintenance Therapy

Gradually after transplantation, rejection prophylaxis can be reduced (i.e. steroid tapering and gradually lowering of CNI levels), as the patient enters the late maintenance phase. Regimens vary between centres and patients, however patients typically end tailored to one or two treatments.

Long-term maintenance therapy is associated with an increased cardiovascular risk and CNI-related nephrotoxicity. Other important side effects include increased risk of opportunistic infections (e.g. cytomegalovirus or Pneumocystis Jirovecii) and malignancies (e.g. post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorder).

Key Points

- Immunology of transplantation surrounds the host’s recognition and response to foreign tissue

- Organ rejection can be divided into hyperacute, acute, and chronic

- Current immunosuppressive agent classes include calcineurin inhibitors, anti-proliferative agents, mTOR Inhibitors, corticosteroids, and monoclonal antibodies

- Long term immunosuppression is associated with increased cardiovascular risk, nephrotoxicity, opportunistic infection risk, and malignancies.