Introduction

Coronary artery disease (CAD), or ischaemic heart disease, is the leading cause of death worldwide. Current prevalence is approximately 6% in men and women aged 40-59, rising to approximately 27% after 80 years of age. More worryingly, there has been a substantial increase in the prevalence of CAD in recent years, especially in higher income countries.

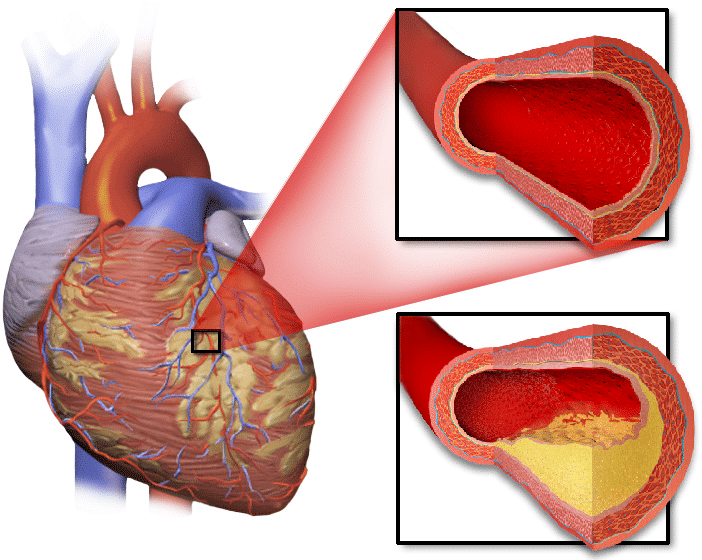

Figure 1 – Arterial Supply of the Heart (A) Anterior view (B) Posterior view

Pathophysiology

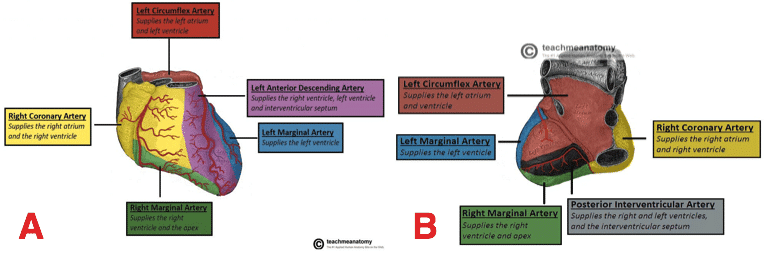

Myocardial tissue is perfused by the coronary arteries. Narrowing or occlusion of these arteries result in reduced blood flow to the myocardium (Fig. 2), thereby reducing the capability to match myocardial metabolic demand.

The most common pathophysiologic mechanism responsible for CAD is the formation of atheromatous plaques on the walls of the coronary arteries, termed atherosclerosis. These plaques significantly reduce the luminal area of the vessels and precipitate the formation of plaque thrombi, which can acutely occlude the vessel and result in a myocardial infarction.

Risk Factors

The main risk factors for CAD are hypertension, hypercholesterolaemia, and diabetes mellitus. Other factors include smoking, obesity, and a strong family history (especially in first-degree relatives).

Clinical Features

Patients with CAD typically present initially with angina pectoris, which describes as a chest pain which is central, heavy, and gripping in nature. Importantly, in cases of stable angina, this typically occurs during exertion, but is relieved with rest.

Other clinical manifestations of CAD includes heart failure and acute coronary syndrome. Acute coronary syndrome (ACS) comprises of unstable angina, non-ST elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI), and ST elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI). The investigation and management of heart failure and ACS is beyond the scope of this article.

CCS Classification for Angina

The CCS classification for angina can be used to quantify symptoms, especially useful in the evaluation of a candidate for coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG):

- Class I – Presence of angina during strenuous, rapid, or prolonged ordinary activity (walking or climbing the stairs)

- Class II – Slight limitation of ordinary activities when they are performed rapidly, after meals, in cold, in wind, under emotional stress, or during the first few hours after waking up

- Class III – Having difficulties walking one or two blocks or climbing one flight of stairs at normal pace and conditions

- Class IV – No exertion needed to trigger angina

Investigations

The gold standard of investigation for patients presenting with suspected CAD is via coronary angiography. This interventional procedure involves contrast being injected into the coronary arteries and serial CT images taken in sync with the patient’s heartbeat; the site and degree of stenosis within the coronary arteries can then be identified. The choice of treatment is often largely influenced by angiography findings.

An echocardiogram (ECHO) should also be requested for any potential CABG candidates, as it provides a measure of left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), a strong prognostic factor in CABG.

Management

Patients with coronary artery disease should typically be started on an anti-platelet agent, a beta-blocker, and a calcium channel blockers, alongside a short-acting nitrate (typically a glyceryl tri-nitrate (GTN)) spray, as first-line treatment for symptomatic relief of angina.

However, the mainstay, definitive treatment for CAD is with revascularisation therapy. This is true in both acute and routine presentations, either via percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) or coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) surgery.

Percutaneous Coronary Intervention

Percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) involves a guidewire introduced via a puncture into the radial or femoral artery, passing up to the coronary arteries under radiological guidance. A catheter containing a balloon is then passed over the guidewire and aligned with the lesion, for the balloon to then be inflated to restore the normal width of the lumen and re-establish blood flow through the artery (Fig. 4).

This process can be repeated to treat multiple lesions in the same procedure. A stent, commonly made of a wired mesh, can be permanently deployed across a lesion(s), reducing the rate of post-PCI re-stenosis. Stents are now almost always indicated in patients undergoing PCI.

Figure 4 – Urgent PCI of stenosis in the proximal LAD, before and after images

Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting

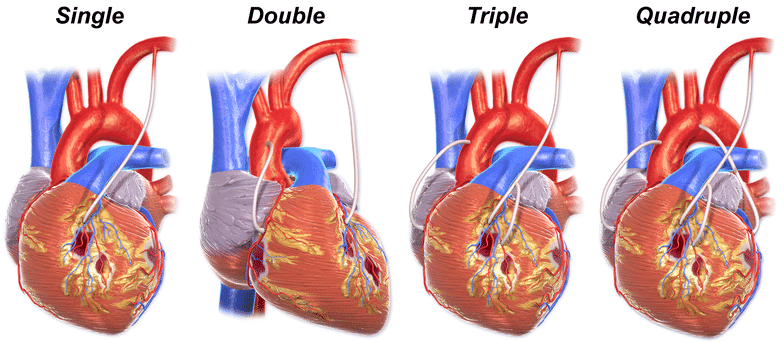

A CABG facilitates the circumvention of blood around a lesion within the coronary artery by connecting a graft to the coronary artery at a site distal to the lesion. This procedure can either be performed with cardiopulmonary bypass (on-pump) or without (off-pump).

Broadly speaking, CABG is preferred to PCI in the presence of complex coronary artery disease. Common indications for a CABG include three-vessel disease, complex two-vessel disease, significant left main stem stenosis (>50%) or equivalent (>70% in LAD or left circumflex), presence of diabetes mellitus, or left ventricular dysfunction or mitral regurgitation.

The great saphenous vein or radial artery are prime candidates for conduits used in a CABG. The left internal mammary artery (LIMA) is often the conduit of choice for an affected left anterior descending artery (LAD). Arterial grafts consistently achieve longer patency periods than their venous counterparts.

Risk Prediction in Cardiac Surgery

The EuroSCORE is useful in estimating the percentage risk of cardiac procedures. It is influenced by patient-related (e.g., age, co-morbidities), cardiac- (e.g., NYHA score, MI history) and surgery-related (e.g., emergency vs routine) factors.

The main risks for CABG are:

- Death

- Pre-, intra-, or postoperative MI

- Stroke

Other operative risks such as bleeding, infections and venous thromboembolism also apply.

Procedure

The CABG procedure varies with anatomical variations, disease complexity and site, and surgeon preference. Commonly, a median sternotomy is performed and the conduits harvested. The cardiopulmonary bypass is commenced, allowing the heart to arrest (cardioplegia*) whilst maintaining systemic perfusion.

The grafts are anastomosed, end-to-side, onto coronary aortotomies via a ‘parachuting’ technique, onto the identified targeted region (both through pre-operative imaging and intra-operative assessment)

The proximal ends of the venous and radial artery grafts are anastomosed to the ascending aorta. This step is not required in a LIMA graft because it is directly supplied by its origin, the left subclavian artery.

The insertion of pacing wires facilitates the control of post-operative atrial fibrillation, which occurs in a third of post-operative patients. Chest drains are inserted prior to closure.

*Cardioplegia lowers myocardial metabolic demand, which prevents myocardial ischaemia during the temporary suspension of coronary blood supply during the procedure.

Figure 5 – Illustration depicting single, double, triple, and quadruple bypass anatomy

Key Points

- Coronary artery disease is the leading cause of death worldwide

- The main risk factors are hypertension, hypercholesterolaemia, and diabetes mellitus

- The gold standard of investigation for patients with suspected coronary artery disease is coronary angiography

- The mainstay of definitive treatment for coronary artery disease is with revascularisation therapy, either via percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) or coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) surgery