Introduction

Post-operative nausea and vomiting (PONV) can be one of the most distressing parts of the surgical journey. It affects approximately 20-30% patients within the first 24-48 hours post-surgery.

The consequences of PONV can include increased anxiety for future surgical procedures, increased recovery time and hospital stay, and, in severe cases, aspiration pneumonia, metabolic alkalosis, and surgical complications.

Risk Factors

There are a number of risk factors for PONV. They can be divided into patient factors, surgical factors, and anaesthetic factors.

Patient factors

- Female gender

- Age (incidence declines throughout adult life)

- Previous PONV or motion sickness

- Use of opioid analgesia

- Non-smoker

Surgical factors

- Intra-abdominal laparoscopic surgery

- Intracranial or middle ear surgery

- Squint surgery (highest incidence of PONV in children)

- Gynaecological surgery, especially ovarian

- Prolonged operative times

- Poor pain control post-operatively

Anaesthetic Factors

- Opiate analgesia or spinal anaesthesia

- Inhalational agents (e.g. Isoflurane, nitrous oxide)

- Prolonged anaesthetic time

- Intraoperative dehydration or bleeding

- Overuse of bag and mask ventilation (leading to gastric dilatation)

Pathophysiology

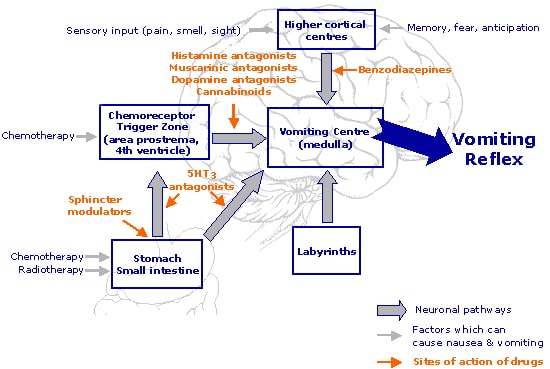

There are two areas in the nervous system that play a key role in the control of vomiting and nausea

- Vomiting centre – located within the lateral reticular formation of the medulla oblongata, which controls and coordinates the movements involved in vomiting

- Chemoreceptor trigger zone – located in the area postrema (situated at the inferoposterior aspect of the 4th ventricle), which is located outside the blood brain barrier and can therefore respond to stimuli in the circulation

The vomiting centre receives input from the chemoreceptor trigger zone, gastrointestinal tract, vestibular system, and higher cortical structures (such as sight, smell and pain), resulting in nausea (Fig. 1). If the stimuli are sufficient, it acts on the diaphragm, stomach and abdominal musculature to initiate vomiting.

A number of neurotransmitters are involved in the control of vomiting. This is important clinically, as they can be targeted by anti-emetic medications. A summary of the neurotransmitters in the vomiting process:

- Chemoreceptor trigger zone – Dopamine and 5HT3 receptors

- Vestibular apparatus – Acetylcholine and Histamine receptors

- Gastrointestinal tract – Dopamine receptors

- Vomiting centre – Histamine and 5HT3 receptors

Clinical Assessment

When assessing a patient suffering with PONV, the first priority is to ensure that they are safe and stable – if in any doubt, an ABCDE approach should be taken. If the patient is drowsy or vomiting there is a risk of aspiration, so airway assessment and use of an nasogastic tube may be required.

Consider the following questions during your assessment of the patient:

- What was the operation? Is it likely to cause PONV?

- Which anaesthetic agents/post-operative drugs have been used?

- Are there other factors contributing to nausea?

- Which antiemetic therapy would suit this patient best?

In addition, it is important to be aware of alternative causes of nausea and vomiting in the post-operative patient, such as infection, gastrointestinal causes (post-operative ileus, bowel obstruction), metabolic causes (hypercalcaemia, uraemia, diabetic ketoacidosis), medication (antibiotics, opioids), neurological causes (raised ICP), or psychiatric causes (anxiety).

Management

The management of post-operative nausea and vomiting can be divided into three areas; prophylactic, conservative and pharmaceutical.

Prophylactic Measures

- Anaesthetic measures – reduce opiates, reduce volatile gases, avoiding spinal anaesthetics

- Prophylactic antiemetic therapy

- Dexamethasone at induction of anaesthesia

Conservative Measures

- Adequate fluid hydration

- Adequate analgesia

- Consider nasogastric tube insertion to aid gastric decompression

Pharmaceutical Measures

A wide variety of pharmacological options are available for anti-emetic action and it is important that the choice of antiemetic is considered by the likely cause of the nausea. Multi-modal therapy is often more effective, therefore add in a different antiemetic to that given in theatre.

- Patients with impaired gastric emptying or gastric stasis should be trailed on a prokinetic agent, such as metoclopramide (dopamine antagonist) or domperidone (dopamine antagonist), unless bowel obstruction is suspected

- A suspected metabolic or biochemical imbalance, such as uraemia, electrolyte imbalance, or cytotoxic agents, causing PONV can be trialled on metoclopramide

- Opioid-induced PONV typically responds well to ondansetron (5-HT3 receptor antagonist) or cyclizine (H1 Histamine receptor antagonist)

Key Points

- Identifying patients who are at risk of post-operative nausea and vomiting will aid in their management

- A range of antiemetic medications are available and are often used in combination

- Nausea and vomiting may be a sign of post-operative complication, such as paralytic ileus