Introduction

Prostate cancer is the most common cancer in men in the UK, accounting for 26% of all male cancer diagnoses, and is estimated that 1 in 8 men will be diagnosed with prostate cancer in their lifetime.

The majority of cases occur in older men, although 25% of cases occur in men younger than 65. Whilst the 10 year survival rate is over 80%, prostate cancer is the cause of death in over 10,000 men in the UK alone each year.

Pathophysiology

Although the exact aetiology of prostate cancer is the subject of ongoing research, it is widely agreed that the growth of prostate cancer is influenced by androgens (testosterone and dihydrotestosterone (DHT)).

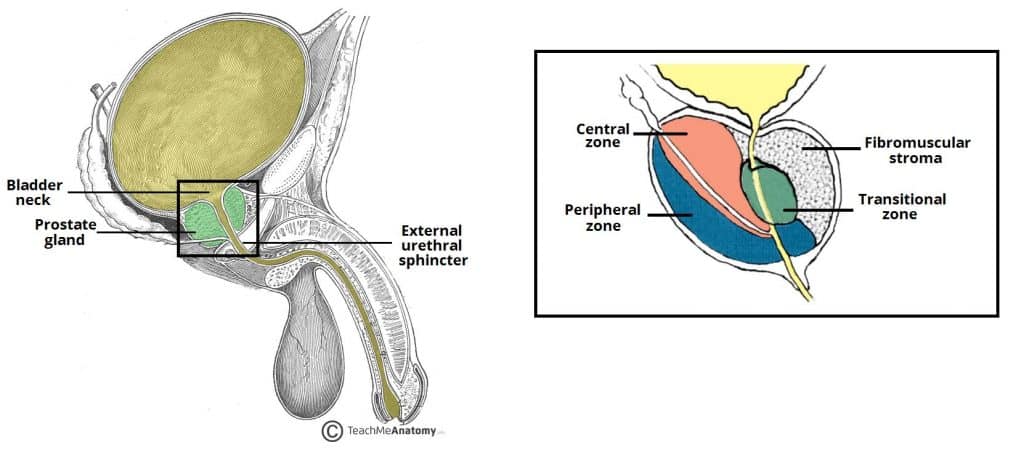

The majority of prostate cancers (>95%) are adenocarcinomas. Over 75% of prostate adenocarcinomas arise from the peripheral zone, with 20% in the transitional zone and 5% in the central zone (Fig. 1). Prostate cancers are often multifocal.

Figure 1 – Sagittal cross-section of the prostate anatomy, demonstrating each zone of the prostate, relative to the urethra and ejaculatory ducts

Prostate adenocarcinomas can be categorised into two types:

- Acinar adenocarcinoma – originates in the glandular cells that line the prostate gland

- This is the most common form of prostate cancer (Fig. 2)

- Ductal adenocarcinoma – originates in the cells that line the ducts of the prostate gland

- This tends to grow and metastasise faster than acinar adenocarcinoma

Risk Factors

The main risk factors for developing prostate cancer are:

- Age, as the incidence of prostate cancer increases with age

- Autopsy studies show an estimated prevalence of 60% for men older than 75 years

- Ethnicity – men of black African or Caribbean ethnicity are twice as likely (one in four) to be diagnosed with prostate cancer in their lifetime when compared to Caucasian men

- Family history of prostate cancer – family history is associated with increased risk of prostate cancer, however only 9% of prostate cancers are thought to be truly inherited.

Genetic predisposition, although rare, also play a part, as men who possess the BRCA2 or BRCA1 gene are at greater risk.

Other less significant modifiable risk factors include obesity, diabetes mellitus, smoking (associated with increased risk of prostate cancer death), and degree of exercise (considered protective).

Clinical Features

Patients can present with a wide variety of symptoms, dependent on stage of the disease. Localised disease can present with lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) including weak urinary stream, increased urinary frequency, and urgency.

More advanced localised disease may also cause haematuria, dysuria, incontinence, haematospermia, suprapubic pain, loin pain, and even rectal tenesmus. Any metastatic disease may cause, amongst others, bone pain, lethargy, anorexia, and unexplained weight loss.

A Digital Rectal Examination (DRE) is essential if a diagnosis of prostate cancer is suspected*, as most prostate adenocarcinomas arise from the posterior peripheral zone. The examination should be checking for evidence of asymmetry, nodularity, or a fixed irregular mass.

*Tumours >0.2mL can be palpable, indeed some may be picked incidentally when performing a DRE for another indication

Differential Diagnosis

- Benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) – a non-cancerous enlargement of the prostate gland, will also cause LUTS symptoms initially

- Prostatitis – inflammation of the prostate gland; patients usually present with perineal pain, with neutrophils seen on urinalysis

- Other causes of haematuria – these may include bladder cancer, urinary stones, urinary tract infections, and pyelonephritis

Investigations

Laboratory Tests

Prostate Specific Antigen (PSA) is a serum protein produced by both malignant and normal healthy cells in the prostate gland. PSA can be elevated secondary to prostate cancer.

However, the PSA can become raised with several other conditions*, including BPH, prostatitis, UTI, recent urological surgery, or urinary retention, reducing its specificity.

*Whilst a DRE can raise the PSA, this is thought to be <0.3ng/mL and should therefore not affect interpretation of the PSA result

| Age Range | Normal PSA |

| 40-49 years | <2.5 ng/mL |

| 50-59 years | <3.5 ng/mL |

| 60-69 years | <4.5 ng/mL |

| >70 years | <6.5 ng/mL |

Table 1 – Guide for normal age-adjusted serum PSA levels

Further calculations using PSA, such as free:total PSA ratio, can be used to increase the accuracy of the test for men with PSA from 4-10; a low free:total ratio is associated with an increased chance of diagnosing prostate cancer. PSA density* can also be used, which is the serum PSA level divided by prostate volume determined by imaging (i.e. TRUS, MRI)

*PSA density >0.14ng/mL2 if often used as a threshold to suggest an increased likelihood of prostate cancer

Prostate Cancer Screening

The screening of asymptomatic men for prostate cancer is a controversial topic. To date, there is no national prostate cancer screening programme in many Western countries.

The European Randomized Study of Screening for Prostate Cancer (ERSPC) showed a significant reduction in prostate cancer mortality at 11 years. This is contrasted to the US-based Prostate, Lung, Colorectal, and Ovarian Cancer (PLCO) Screening Trial which found no reduction in prostate cancer mortality at 10 years. However, the PLCO was limited by a contamination (PSA-testing) rate of up to 70% in the control arm of the study.

Nonetheless, there remains questions regarding the benefit of widespread screening and concern regarding over-diagnosis and over-treatment in screened populations. Regardless, for those men who are offered a PSA screening test, counselling prior to testing is essential.

Further Investigation

In men thought to be at risk of prostate cancer, such as with a raised PSA or abnormal DRE, a multi-parametric MRI scan of the prostate (mp-MRI) should be performed. A mp-MRI can identify abnormal areas of the prostate, which can then be targeted for biopsy.

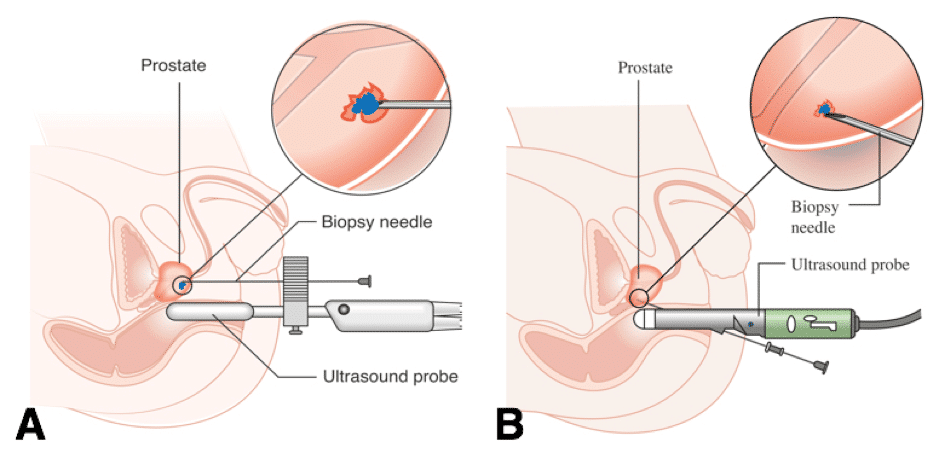

The current standard method for diagnosing prostate cancer is through biopsies of prostatic tissue: Although there are two potential methods, there is a general trend towards performing only transperineal due to the decreased risk of infection:

- Transperineal biopsy – can be done either as a template biopsy (Fig. 3A), which used a grid-like template, sampling of prostatic tissue in a systematic manner, or as a freehand biopsy, where sampling is guided by both intra-procedure ultrasound and mpMRI

- TransRectal UltraSound-guided (TRUS) biopsy (Fig. 3B) – this involves sampling the prostate transrectally, using ultrasound as guidance and then sampling of prostatic tissue in a systematic manner

Figure 3 – schematic representation of (A) transperineal and (B) transrectal biopsy techniques

Repeat prostate biopsy after previous negative biopsy is recommended for men with rising or persistently elevated PSA and/or suspicious DRE.

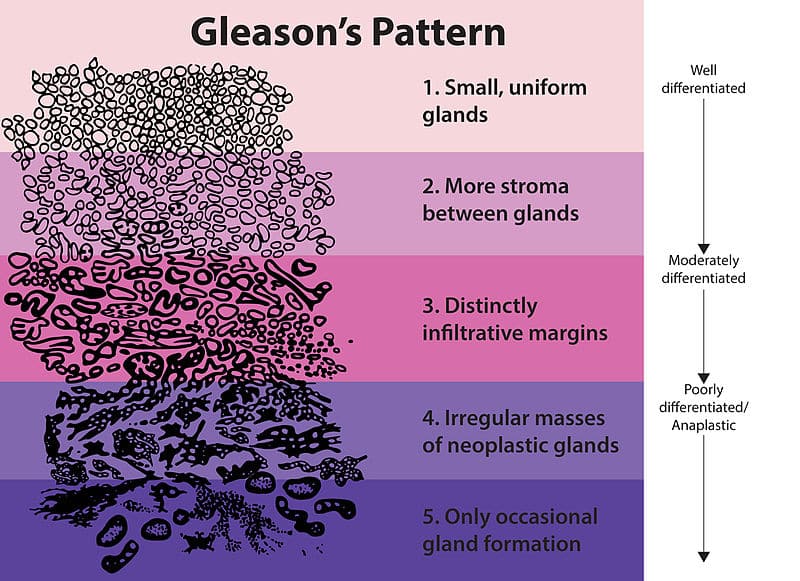

Gleason Grading System

The Gleason grading system is a scoring system by which prostate cancers are graded, based upon their histological appearance.

The sample of prostate tissue is assigned a score according to its differentiation (Fig. 4) and the Gleason Score is then calculated as the sum of the most common growth pattern + the second most common growth pattern seen.

In essence, the lowest score that can be assigned to an individual with prostate cancer is Gleason 3+3. Higher Gleason scores are associated with a poorer prognosis.

Prostate cancer is a heterogeneous disease with patient outcomes depending on risk stratification. In clinical practice, Gleason scores alone are not used to determine prognosis and recurrence risk, instead the score is used in conjunction with PSA levels and TNM staging.

Imaging

Typically a patient has already undergone a MRI scan of the prostate for the initial diagnosis of a prostate cancer. Once confirmed, further staging imaging is required.

Staging of prostate cancer is typically done for men with intermediate or high-risk disease. Staging is accomplished with CT chest-abdomen-pelvis scan and PET-CT nuclear medicine scan.

Management

Every patient with prostate cancer should be discussed at a specialist prostate cancer multidisciplinary team (MDT) meeting.

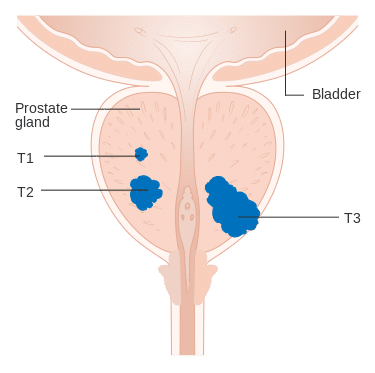

Management of localised cancer relates directly to risk stratification based on PSA levels, Gleason score, and T staging (from TNM). NICE produced risk stratification for prostate cancer based on the following parameters:

| Level of Risk | PSA (ng/ml) | Gleason Score | Clinical Stage |

| Low | <10 | ≤6 | T1-T2a |

| Intermediate | 10-20 | 7 | T2b |

| High* | >20 | 8-10 | ≥T2c |

*High-risk localised prostate cancer is included in the definition of locally advanced prostate cancer

Depending on the risk stratification will determine what treatment options should be offered to the patient

- Low risk disease: Most can be offered active surveillance, radical treatments offered to those who show evidence of disease progression

- Intermediate and high risk disease: Radical treatment options should be discussed with all men with intermediate risk disease and high risk disease with realistic disease control. Those with intermediate risk can also be offered active surveillance (should not be offered for high risk disease)

- Metastatic disease: Chemotherapy agents and anti-hormonal agents can be used in metastatic prostate cancer

- Castrate–resistant disease: Those who demonstrate evidence of hormone-relapsed disease can be considered for further chemotherapy agents, such as Docetaxel. Corticosteroids can be offered as third-line hormonal therapy after androgen deprivation therapy and anti-androgen therapy to men with hormone-relapsed prostate cancer

Watchful Waiting and Active Surveillance

Watchful waiting is a symptom-guided approach* to prostate cancer management where therapy is deferred and initiated at time of symptomatic disease. The intent is not curative.

Active surveillance can be offered to select patients with curable low-risk disease and for some cases of intermediate-risk disease. Curative treatment is considered when disease progression is noted, which can defer or avoid considerable morbidity associated with radical therapy.

Active surveillance requires monitoring of patients with 3-monthly PSA, 6 month to yearly DRE, and re-biopsy at 1-3 yearly intervals assessing for progression and intervening at the appropriate time. Mp-MRI is also being used increasingly in such protocols.

*Watchful waiting is generally reserved for older patients with lower life expectancy and can be offered for any stage of prostate cancer; there is no pre-define follow up protocol and management is largely guided by patient goals of care and maintaining quality of life

Surgical Management

The mainstay surgical treatment for prostate cancer consists of a radical prostatectomy. This involves the removal of the prostate gland, resection of the seminal vesicles, along with the surrounding tissue +/- dissection of the pelvic lymph nodes.

This procedure can also be performed with an open approach, laparoscopically or robotically.

Side effects of radical prostatectomy include erectile dysfunction (affecting 60-90% of men), stress incontinence and bladder neck stenosis.

Radiotherapy

External-beam radiotherapy and brachytherapy are both commonly used alternatives as a form of curative intervention for localised prostate cancer.

Brachytherapy involves the transperineal implantation of radioactive seeds (usually Iodine-125) directly into the prostate gland, whilst external-beam radiotherapy uses focused radiotherapy to target the prostate gland and limiting damage to surrounding tissues.

Anti-Androgen Therapy and Chemotherapy

Androgren deprivation therapy (ADT) is the mainstay of management of metastatic prostate cancer and improves outcomes in patients undergoing radiotherapy, as prostate cancer cells undergo apoptosis when deprived of testosterone.

Options include anti-androgens (e.g. bicalutamide), gonadotrophin-releasing hormone (GnRH) receptor agonists (e.g. goserelin) and antagonists (e.g. degarelix) or surgical castration. Newer hormone therapies now exist, such as the drugs enzalutamide and abiraterone, acting to lower levels of serum testosterone.

Chemotherapy is usually only indicated in patients with metastatic prostate cancer. Some examples of chemotherapy drugs used include docetaxel or cabazitaxel.

Key Points

- Most prostate cancers are acinar adenocarcinomas arising from the peripheral zone

- Age, ethnicity, and family history are key risk factors for the development of prostate cancer

- Diagnosis and prognosis are achieved via a Transrectal or Transperineal biopsy of the prostate gland leading to Gleason scoring, alongside DRE findings, PSA, and radiological staging

- Radical prostatectomy, external-beam radiotherapy, and brachytherapy are the mainstay treatments of localised or locally advanced prostate cancer

- Anti-androgen therapy is effective in metastatic disease