Introduction

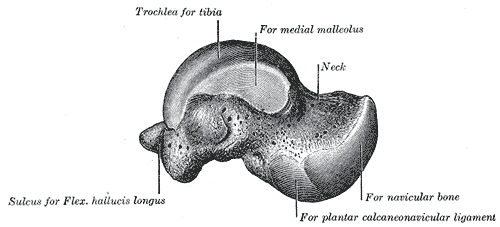

The talus is the second largest tarsal bone (Fig. 1) and is also the second most commonly fractured tarsal bone.

Talar fractures typically occur following high-energy trauma, such as a fall from height or road traffic accident, during which the ankle is forced in to dorsiflexion; this causes the talus to press against the tibial plafond, resulting in a fracture.

Most talar fractures occur through the talar neck (~50%) or less commonly through the body, lateral process, or posterior process of the talar bone.

The talus is reliant predominantly on extraosseous arterial supply, which is highly susceptible to interruption in the context of fractures; consequently, the talus is at high risk of avascular necrosis after fracture.

Clinical Features

Patients will present with a history of high-impact trauma, with immediate pain and swelling around the ankle. If the talus is dislocated, there will be a clear deformity. In isolated uncomplicated injuries, the main presenting symptoms are predominately pain and an inability to weight bear.

On examination, patients will be unable to dorsiflex or plantarflex their ankle. It is important to check if this is an open fracture. Moreover, in the context of talar dislocation, the overlying skin may be ‘threatened’ (i.e. white, non-blanching, and tethered), suggesting an impending conversion to an open injury. Always ensure to assess the distal neurovascular status.

Differential Diagnosis

The main differential diagnoses to consider in cases are ankle fractures and Pilon fractures.

Investigations

Patients with talar fractures often present following high-energy traumatic injuries, therefore an A to E approach first following ATLS principles is essential.

In the context of a suspected talar fracture, initial investigations of all suspected talar fractures requires plain film radiographs, both antero-posterior and lateral views.

Lateral views should ideally be taken in dorsiflexion and plantarflexion, in attempt to differentiate between type I and II injuries (see below), as plantar flexion will reduce any subluxation present.

For complex injuries, CT imaging (Fig. 2) may be required for further detailed assessment and aid in management planning.

Figure 2 – Anterior talar fracture, as seen on CT imaging

Classification

Talar neck fractures can be classified by the Hawkins Classification. This aids in both management planning and can determine the risk of avascular necrosis (AVN).

|

Type |

Description |

Risk of AVN |

|

I |

Undisplaced |

0-15% |

|

II |

Subtalar dislocation |

20-50% |

|

III |

Subtalar and tibiotalar dislocation |

90-100% |

|

IV |

Subtalar, tibiotalar, and talonavicular dislocation |

100% |

Table 1 – The Hawkins Classification of Talar Fractures

Management

Management of talar neck fractures is dependent on their Hawkins classification.

Generally, however, all undisplaced neurovascularly intact fractures may be managed conservatively in a non-weight bearing orthosis, whilst all displaced fractures require immediate reduction (in the emergency department) and then subsequent surgical repair.

Type I Fractures

Type I fractures can be treated conservatively in a plaster with non-weight bearing crutches for approximately 3 months. Following this, the region should be assessed for evidence of union and avascular necrosis in fracture clinic.

Type II to IV Fractures

Type II, III, and IV fractures should initially be managed with attempted closed reduction in the Emergency Department. Once reduced, a Plaster of Paris cast should be placed and repeat radiographs obtained to ensure it remains in position. If reduction is not possible, open reduction out-of-hours is needed.

Definitive surgical fixation is required on the next available list with the correct expertise, with referral onward to a tertiary centre if needed. Post-operatively, patients will require an extended period of non-weight bearing status.

Complications

The main complication of talar fractures is avascular necrosis, occurring in 17% of cases following talar fractures*. It occurs most commonly after Hawkins type II-IV fractures (this is not influenced by the anatomical reduction performed).

Osteoarthritis may occur secondary to avascular necrosis or any malunion involving the talar joints. If this is severe, arthrodesis may have to be considered.

*Hawkins sign is a line of subchondral lucency of the talar dome on plain radiograph visible 6-8 weeks following injury; this is indicative of relative bone reabsorption indicating sufficient vascularity of the talus and suggests low risk of avascular necrosis

Key Points

- The talus is the second most common tarsal bone to fracture

- They typically present with a history of high-impact trauma, with immediate pain and swelling around the ankle

- Initial assessment warrants plain film radiographs, both antero-posterior and lateral

- Classification is via Hawkins classification, which can aid management options

- Talar fractures are at high risk of avascular necrosis