Introduction

Compartment syndrome is defined as a critical pressure increase within a confined compartmental space. Any fascial compartment can be affected, however the most common sites affected are in the leg, thigh, forearm, foot, hand and buttock.

Whilst it is a treatable condition, a missed diagnosis of compartment syndrome can lead to limb loss, significant morbidity, and even death.

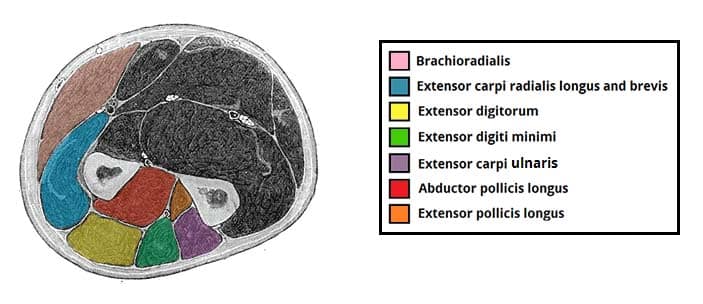

Figure 1 – Cross section of the muscles of the distal forearm, highlighting those of the posterior compartment

Pathophysiology

Compartment syndrome typically occurs following high-energy trauma crush injuries, or fractures that cause vascular injury. Other causes include iatrogenic vascular injury, tight casts or splints, deep vein thrombosis, and post-reperfusion swelling.

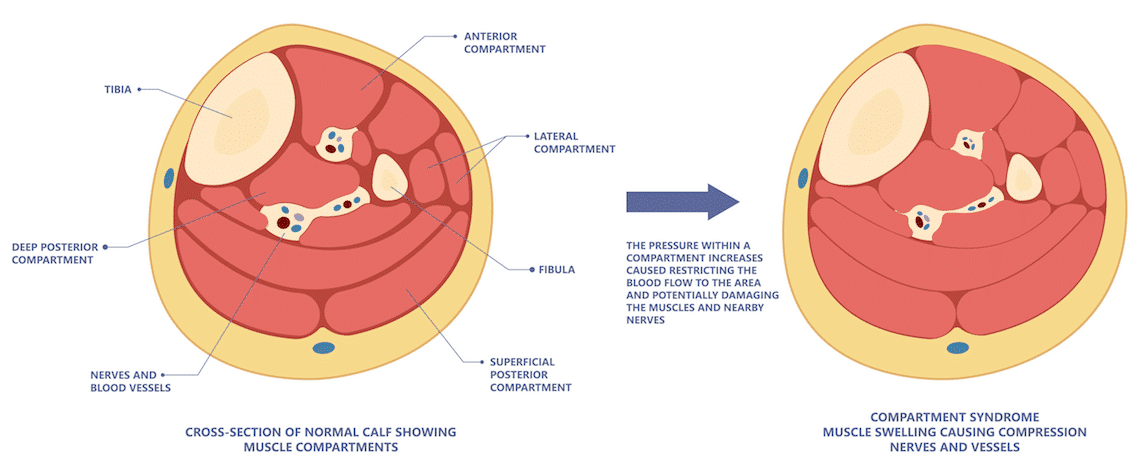

Fascial compartments are closed and cannot be distended; consequently, any fluid that is deposited therein without adequate venous drainage will cause an increase in the intra-compartmental pressure (Fig. 2).

As pressure increase, the veins will be compressed. This increases the hydrostatic pressure within them, causing fluid to move down its gradient and out of the veins in to the compartment. This increases the intra-compartmental pressure further.

Next, the traversing nerves are compressed. This causes a sensory +/- motor deficit in the distal distribution. Paraesthesia is therefore a common symptom.

As the intra-compartmental pressure reaches the diastolic blood pressure, the arterial inflow will be compromised, and the leg will become ischaemic.

Clinical Features

Symptoms tend to present within hours, although it can develop up to 48 hours post-insult.

The most reliable symptom of compartment syndrome is severe pain, disproportionate to the injury, which is not readily improved with initial measures (such as analgesia, elevation to the level of the heart, and splitting a tight cast). The pain is made worse by passively stretching the muscle bellies traversing the affected fascial compartment.

Parasthesia can occur, however whilst the patient may have had a neuropraxia at the time of the injury, it is the presence of evolving neurology that is most important.

The affected compartment may feel tense (compared to the contralateral side), but will not generally be swollen (as the fascial compartment is only minimally distensible).

If the disease progresses, acute limb ischaemia will subsequently develop (often referred to as the ‘5 P’s’): Pain (disproportionate to the injury), Pallor (or mottled, which becomes non-blanching), Perishingly cold, Paralysis, and Pulselessness.

Investigations

Compartment syndrome is a clinical diagnosis, based on the symptoms and risk factors present. Clinicians should therefore have a high degree of clinical suspicion for compartment syndrome in post-operative patients.

The most reliable diagnostic test is siting an intra-compartmental pressure monitor, which may be utilised where there is clinical uncertainty, such as in atypical presentations or if the patient is unconscious / intubated (normal compartmental pressures are 0-8mm Hg)

A creatine kinase (CK) level may aid diagnosis, if elevated (or trending upwards).

Management

The most important part of the management is early recognition and immediate surgical treatment via urgent fasciotomies (Fig. 3).

Prior to definitive intervention, additional management steps should include:

- Keep the limb at a neutral level with the patient (do not elevate or lower)

- Improve oxygen delivery with high flow oxygen

- Augment blood pressure with bolus of intravenous crystalloid fluids

- This transiently improves perfusion of the affected limb

- Remove all dressings, splints, or casts, down to the skin (no layers of any dressing must be left circumferentially)

- Treat symptomatically with opioid analgesia (usually intravenous)

Once fasciotomies have been performed, the skin incisions are left open and a re-look is planned for 24-48 hours. This is to assess for any dead tissue that needs to be debrided. If the remaining tissues are healthy, the wounds can then be closed (the subtending fascia is often left open).

Monitor renal function closely, due to the potential effects of rhabdomyolysis or reperfusion injury.

Figure 3 – Fasciotomy for Compartment Syndrome in Forearm

Key Points

- Compartment syndrome is most common in the lower limbs, typically following traumatic injury or fractures

- Diagnosis is clinical, the main symptom being pain disproportionate to the injury or worsening despite treatment

- Definitive treatment is with an emergency open fasciotomy/fasciotomies.

- Monitor the patient for rhabdomyolysis and reperfusion syndrome as potential complications