Introduction

Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) is a malignant tumour of keratinocytes, arising from the epidermal layer of the skin. SCC is the second most common form of skin cancer, after basal cell carcinoma, accounting for 20% of all cutaneous malignancies, and has an incidence of 10,000 per year in the UK.

Most SCC arise from cumulative prolonged exposure to ultraviolet (UV) radiation, primarily UVB. As such, they are typically located found on areas exposed to high doses of UV radiation, such as the head & neck, arms, and legs, and are more common in men.

Exposure to UV radiation causes numerous DNA mutations in multiple somatic genes, such as the p53 tumour suppressor gene. SCC can arise from premalignant lesions such as Bowen’s disease, actinic keratoses, keratin horns or leukoplakia.

Whilst uncommon, SCC has the potential to metastasise via the lymphatic system to regional lymph nodes and any organ, most commonly lungs, liver, brain, bones and skin.

Risk Factors

- Cumulative prolonged exposure to UV light, such as excessive sunbed use

- Chronic wounds and inflammation

- A SCC arising in chronic ulcers and scars (particularly burns scars) is known as a Marjolin’s ulcer

- Immunosupression

- Pre-malignancy conditions, such as Bowen’s disease or actinic keratoses

- Smoking (particularly in lip SCC)

Certain viruses have also been associated with the development of SCC, including herpes simplex or human papilloma virus

Clinical Features

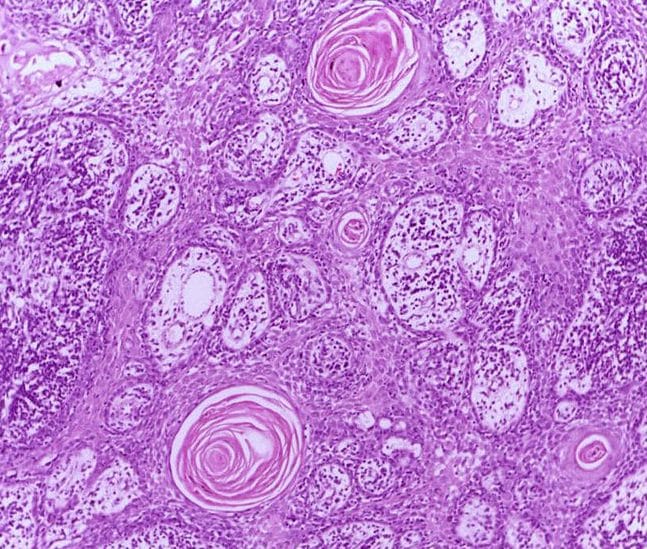

The appearance of SCC can be highly variable. The can appear nodular, indurated, or keratinised (Fig. 2) with associated ulceration or bleeding.

Their growth may be over weeks to months, and size is variable, from a few millimetres to several centimetres in diameter.

They are typically located on sun-exposed sites, such as the hands, forearms, lower limbs, and the “H zone” of the face (pinnae, pre-auricular, medial and lateral acanthi, eyelids, nose and lips).

Differential Diagnoses

The main differentials to consider for SCC are other forms of skin cancer, such as BCC or melanoma. Other differentials to consider include pre-malignant conditions (e.g. Bowen’s disease or Actinic Keratosis, Fig. 3), Keratoacanthoma (rapidly growing keratinising nodules, well-demarcated), verrucous carcinoma, or cutaneous horns.

Bowen’s Disease

Bowen’s disease (also termed SCC in-situ) is a growth of cancerous cells confined to the outer layer of the skin. Importantly, Bowen’s disease is seen as a pre-cancerous condition, as it can progress into SCC.

Most cases develop as a result of chronic UV radiation exposure, and often present on sun-exposed areas of the body, such as the face, neck, arms, and lower legs. Patients receiving long-term immunosuppression medication are also at risk.

Bowen’s disease will present as a slow-growing, small, red, and scaly lesion. Since Bowen’s disease will often resemble other skin conditions, such as psoriasis, a biopsy is required for diagnosis.

Topical treatments, as discussed above, are usually sufficient for the management of the condition. However, primary prevention is as important for this condition as in SCC cases.

Investigations

A full history and examination should be performed, including palpation of regional lymph node basins.

Dermoscopy is recommended to aid diagnosis. The most common features of SCC on dermoscopy are white circles or structureless areas, looped blood vessels, and a central keratin plug.

Figure 3 – An area of Actinic Keratosis on a patients cheek

The mainstay of definitive diagnosis for SCC comes from biopsy (see below). Small well-demarcated lesions are amenable to excision biopsy with peripheral margins, whilst larger lesions warrant ideally an incisional biopsy for tissue diagnosis.

If there is suspicion of lymph node or metastasis, then further imaging +/- fine needle aspiration of suspicious nodes should be arranged, as per MDT discussion.

Types of Biopsies

Several types are biopsies are available, all aim to obtain a histological sample however each come with advantages and disadvantages:

- Excisional biopsy – the whole lesion is excised, together with a margin of normal tissue

- Advantages = excises adequate sample for histological analysis, removing all abnormal tissue; disadvantages = often requires more time and results in a larger scar

- Incisional biopsy – only a portion of the lesion is removed, via a relatively smaller skin incision

- Advantages = quicker procedure, less invasive than excisional biopsy; disadvantages = lesion will still require further treatment if warranted

- Punch biopsy – a small deep hole is punched out of the lesion, with a small cylindrical sample of tissue removed

- Advantages = quicker procedure, obtains a full-thickness sample, good cosmetic outcome; disadvantages = incorrect area of sample may be sampled, lesion will still require further treatment if warranted

Excisional biopsy is generally indicated for lesions in an easily accessible area, not in a cosmetically sensitive area, and not near vital anatomical structures. Conversely, incisional and punch biopsies are typically used in larger tumours.

Classification

SCCs can be graded based on their Broder’s grade, which is determined by the ratio of differentiated to undifferentiated cells:

- Grade I = 3:1

- Grade II = 1:1

- Grade III = 1:3

- Grade IV = no differentiation

SCC can be classified into low risk, high risk, or very high risk lesions, determined by (amongst others) their size, thickness, evidence of perineural invasion or lymphovascular invasion, degree of differentiation, presence of clear margins, and location.

Management

The first line management for resectable SCC is surgical; non-surgical options are only used as adjuncts or where surgery is not feasible.

Surgical Treatment

The standard surgical treatment is with an excision biopsy, with the peripheral margins taken dependent on the risk status of the patient:

- low risk ≥ 4mm

- high risk ≥ 6mm

- very high risk ≥ 10mm

The deep margins taken should be the next clear surgical plane (or in scalp lesions, down to the galea)

Further wide local excision (with likely delayed reconstruction), Mohs micrographic surgery, or adjuvant radiotherapy may be offered to patients with one or more involved or close margins if there are any high risk factors.

Dermatologists may perform curettage and cautery for immunocompetent patients who have small (<1cm), clinically low risk SCC

Non-Surgical treatment

Multiple non-surgical options are also available to patients with SCC in certain cases.

Primary radiotherapy may be a treatment option if surgery is not feasible or would result in an unacceptable functional or aesthetic outcome. Adjuvant radiotherapy is used for patients with close or involved margins if further surgery is not possible, or for patients with clear margins but multiple high risk factors where the chance of local recurrence is high.

Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors can be used in locally advanced SCC where curative surgery or radiotherapy is not no reasonable, or in cases of metastatic SCC.

Chemotherapy is often used as a third line, in people who are not suitable for immune checkpoint inhibitors, however is often poorly tolerated in frailer or co-morbid patients, and usually has a short lived response.

Prognosis

Low risk SCC have a 40% lifetime risk of further skin cancers, whilst high and very high risk SCC have an even higher risk of around 80% lifetime risk.

The overall metastatic potential of SCC is 3%, however the 10 year survival for those with metastasis being <10%.

Key Points

- Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) is a malignant tumour of keratinocytes

- Its main risk factor is cumulative prolonged exposure to UV light

- Definitive diagnosis is made via biopsy and surgical excision forms the mainstay of management