Introduction

The tibia is one of the most common long bones to be fractured, and it can be fractured proximally, distally, or along its shaft.

The shaft is vulnerable to both direct injuries, from a fall or from a direct blow, and indirect injuries, through twisting or bending forces.

Due to the lack of a significant soft tissue envelope (particularly anteromedial) and the fascial compartments present in the lower leg, the risk of open fractures and compartment syndrome with tibial fractures are greater.

Clinical Features

Patients will present with a history of trauma, however obtaining an accurate description of the injury (including direct and indirect forces that occurred) can suggest potential associated soft tissue injuries or other fractures present.

Patients will complain of severe pain* in the lower leg and an inability to weight bear. On examination, there may be a clear deformity (such as angulation or malrotation) and significant swelling and bruising.

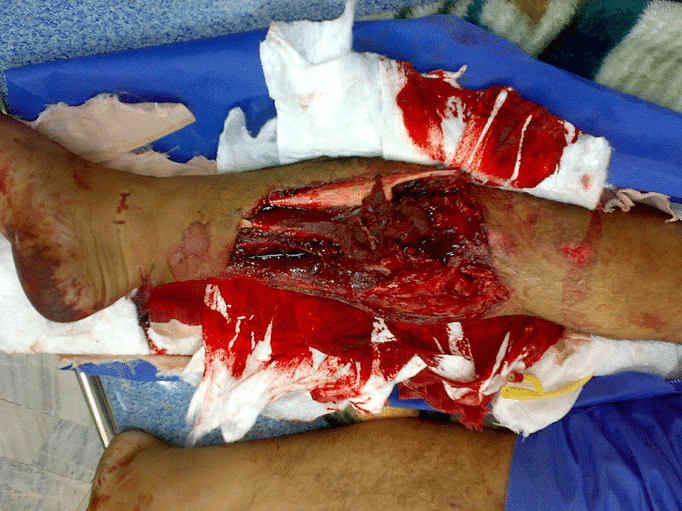

Careful inspection of the skin is essential to assess for the possibility of an open fracture, if not already evident (Fig. 2). A full neurovascular examination should be performed to assess for any concurrent vascular injury or peripheral nerve damage.

*Tibial shaft fractures are high risk for compartment syndrome, any pain out of proportion to the injury and pain significantly worse on passive stretch of the affected compartments is key

Differential Diagnosis

As most cases present following a fall or trauma, differentials include tibial plateau fractures, ankle fractures, fibular fractures, or soft tissue injury.

Investigations

Patients presenting following a major trauma should be investigated and managed as per the ATLS protocol. Urgent bloods, including a coagulation and Group and Save, should be sent.

Imaging

Full length antero-posterior (AP) and lateral plain film radiographs of the tibia and fibula should be requested, which need to also include the knee and ankle.

In cases of potential intra-articular extension, CT imaging will be indicated to evaluate. For any suspected a spiral fracture of the distal tibia, a CT scan is also required, to assess for a fracture of the posterior malleolus.

There may also be an associated fibula fracture, the location of which can correlate to the degree of energy causing the injury; high energy mechanisms often result in a fibula fracture at the same level as the tibia, whilst low energy fractures often result in a fibula fracture at a different level.

Management

The tibia should be realigned as soon as possible, ideally in A&E under analgesia / conscious sedation; whilst exact anatomical reduction is not required, the tibia should be brought approximately to length and rotation. Any open fracture must be managed accordingly.

Following reduction, an above knee backslab (in slight flexion at the knee and neutral dorsiflexion at the ankle) should be applied to control rotation. The limb must be elevated immediately and closely monitored for signs of compartment syndrome.

Post-manipulation plain radiographs should be performed and the neurovascular status of the limb re-assessed and documented.

Most tibial shaft fractures are managed surgically. Urgent operative intervention is required in the context of an acute compartment syndrome, an ischaemic limb, or an open fracture.

Non-operative management with a Sarmiento cast should be considered in closed stable tibial fractures and must be discussed with the patient as an alternative to operative intervention.

Surgical Management

Intramedullary (IM) nailing is the most commonly used method of fixing tibial shaft fractures, providing a stable construct through a minimally invasive approach, with a high success rate. Post-operatively, patients are usually able to fully weight bear immediately.

Particularly proximal or distal fractures, especially those which extend into the joint, may require open reduction internal fixation (ORIF) with locking plates. Those with multiple injuries may require temporary external fixation if they are not stable enough to undergo definitive surgery.

Associated fractures of the fibula can usually be left alone as they heal very well once the tibial fracture has been stabilised.

Complications

The main significant risks of a tibial shaft fracture are compartment syndrome, ischaemic limb, or open fractures.

Malunion can also occur, especially if fractures treated non-operatively. Non-union is less common, occurring in <1% cases.

Key Points

- Tibial fractures typically present following a high impact injury, with associated injuries

- Patients will complain of severe pain in the lower leg and an inability to weight bear; ensure to check for any evidence of an open fracture and fully examine the neurovascular status

- Full length antero-posterior and lateral plain film radiographs of the tibia and fibula are required, including the knee and ankle

- Most tibial shaft fractures are managed surgically, with intra-medullary nailing being the most common