Introduction

Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD) is a condition whereby gastric contents from the stomach leaks up into the oesophagus.

It is a common problem, affecting around a quarter of the population in many countries to varying degrees of severity; GORD can represent around 4% of primary care appointments. It is twice as common in men compared to women.

In this article, we shall look at the risk factors, clinical features and management of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease.

Pathophysiology

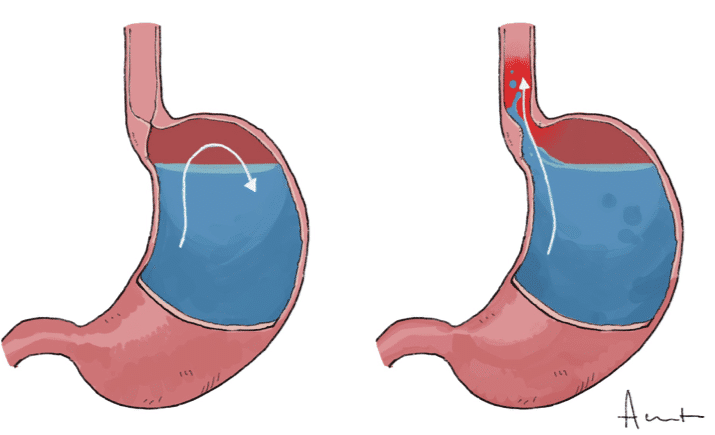

The lower oesophageal sphincter controls the passage of contents from the oesophagus to the stomach. As part of its normal function, episodic sphincter relaxation is expected, yet in patients with GORD these episodes become more frequent and allow the reflux of gastric contents into the oesophagus (Fig. 1).

The repeated refluxed acidic gastric contents (or rarely alkaline bile) result in inflammation to the oesophageal mucosa. The presence of a hiatus hernia can increase these reflux episodes, due to disruption to the oesophageal sphincter. Patients with increased abdominal pressure, such as with pregnancy and obesity, will also have increase risk of reflux.

Figure 1 – Illustration demonstrating Gastro-Oesophageal Reflux Disease

Risk Factors

The main risk factors for GORD include obesity, smoking, alcohol intake, pregnancy, and male gender.

Clinical Features

The main symptom of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease is chest pain. This is classically a burning retrosternal sensation, worse after meals, lying down / bending over, or straining, and can be relieved (at least partially) by antacids.

Additional symptoms may include excessive belching, water brash sensation, or a nocturnal or chronic cough (or less commonly recurrent chest infections). Always check for red flag symptoms (dysphagia, weight loss, early satiety, malaise and loss of appetite) which may suggest an underlying malignancy.

Examination is typically unremarkable.

The Los Angeles Classification of Reflux

The Los Angeles classification can be used to grade reflux oesophagitis based on severity from the endoscopic findings of mucosal breaks in the distal oesophagus:

- Grade A – breaks ≤5mm

- Grade B – breaks >5mm

- Grade C – breaks extending between the tops of ≥2 mucosal folds, but<75% of circumference

- Grade D – circumferential breaks (≥75%)

Differential Diagnosis

Important gastrointestinal differentials to consider include upper GI malignancy (oesophageal or gastric) or peptic ulcer disease

It is also important not to miss cardiac or biliary disease, such as coronary artery disease or biliary colic, as they can be common mimics of the episodic reflux disease

Investigations

In most patients, a clinical diagnosis is reached simply from a good history and resolution of symptoms after a trial of a proton-pump inhibitor.

However, the presence of any red-flag symptoms requires urgent further investigation for a suspected upper GI malignancy:

- Any patient with dysphagia

- Any patient >55yrs with weight loss and upper abdominal pain, dyspepsia, or reflux

- Patients with persistent symptoms, despite trialling conservative management

Imaging

24hr pH monitoring is the gold standard for diagnosis of GORD (see below). It can quantify the burden of reflux disease and is especially important for patients in whom medical treatment has failed and surgery is considered.

Patients with persistent GORD or those with red-flag symptoms will often undergo an upper GI endoscopy (OGD) to rule out any underlying malignancy present, to quantify any oesophagitis present, and to assess for any complications of reflux disease (such as Barrett’s oesophagus), The presence of a hiatus hernia can also be assessed for with endoscopy

Oesophageal manometry is often used in severe cases to exclude any evidence of concurrent oesophageal dysmotility.

pH Monitoring Studies

pH monitoring studies assess various criteria such as the amount of time acid is present in the oesophagus and the correlation between the presence of acid and the patient’s symptoms.

This produces an algorithmic score called the DeMeester score and can help determine a patient’s symptom / reflux correlation

Management

All patients with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease should be advised to take conservative steps in its management, including avoiding known precipitants (alcohol, coffee, fatty foods), weight loss, and smoking cessation, where appropriate

Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) are the first-line treatment and are very effective for the majority of patients. Symptoms tend to recur rapidly after ceasing to take PPIs and so many patients are likely to remain on them long-term (unless they proceed to surgery).

Surgical Management

There are three main indications for anti-reflux surgery in gastro-oesophageal reflux disease:

- Failure to respond (or only a partial response) to medical therapy

- Patient preference to avoid life-long medication

- Patients with complications of GORD* (in particular respiratory complications, such as recurrent pneumonia)

Surgery has been shown to be more effective than medical treatment in terms of symptom relief, quality of life improvement, and cost. However, due to associated complications and side-effects, many patients are understandably reluctant to accept it.

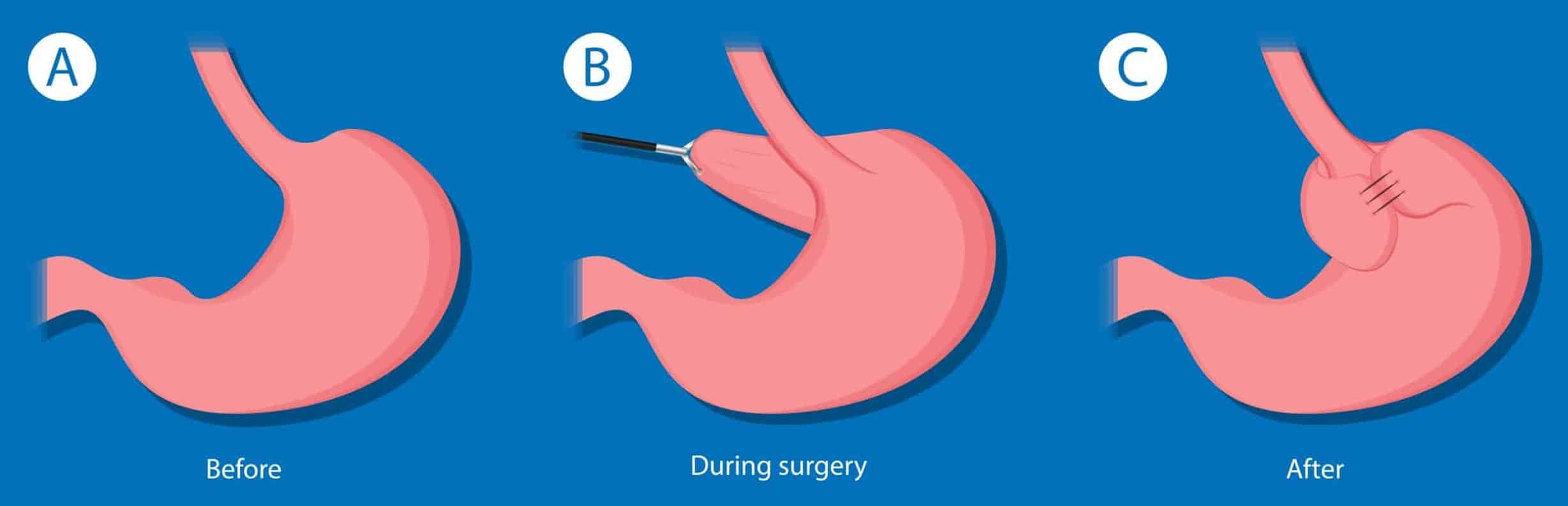

The main surgical intervention that can be offered for patients with GORD is a fundoplication (Fig. 3), whereby the gastro-oesophageal junction and hiatus are dissected and the fundus wrapped around the GOJ, recreating a physiological lower oesophageal sphincter. The hiatal opening in the diaphragm is then narrowed.

Several different approaches to the procedure have been described, differing in direction and completeness of the wrap (such as the posterior 360 (Nissen’s) approach or the partial anterior). The main side-effects of anti-reflux surgery are dysphagia and bloating, however these often settle after a few weeks as the post-operative swelling recedes.

*There is no evidence to suggest anti-reflux surgery reduces cancer risk from Barrett’s oesophagus

Figure 3 – A Nissen fundoplication, where a 360 posterior fundoplication with the gastric fundus is wrapped around the oesophageal sphincter

Complications

The main complications of GORD are aspiration pneumonia, Barrett’s oesophagus, oesophageal strictures, and oesophageal cancer. Around 10% patients with GORD will have already developed Barrett’s oesophagus by the time they seek medical attention.

The 7yr risk of adenocarcinoma in patients with GORD is about 0.1%, in cases where the initial endoscopy is absent of strictures, Barrett’s metaplasia, or adenocarcinoma.

Key Points

- Patients with GORD will typically present with burning retrosternal chest pain, worse after certain meals or lying down

- Gold standard diagnosis is made with pH Monitoring Studies

- The main role of endoscopy is to exclude underlying malignancy and investigate for complications of reflux, but is not required in the majority of patients with dyspepsia

- Medical management is the mainstay of treatment, using of lifestyle changes and proton pump inhibitors