Introduction

Barrett’s oesophagus is defined as an oesophagus in which any portion of the normal distal squamous epithelial lining has been replaced by metaplastic columnar epithelium through metaplasia

It occurs in those with chronic gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD). Its prevalence ranges from 0.5-2% in most high-income countries and around 10% patients with GORD will have developed Barrett’s oesophagus at the time of initial presentation.

In this article, we shall look at the causes, investigations, and management of Barrett’s oesophagus.

Pathophysiology

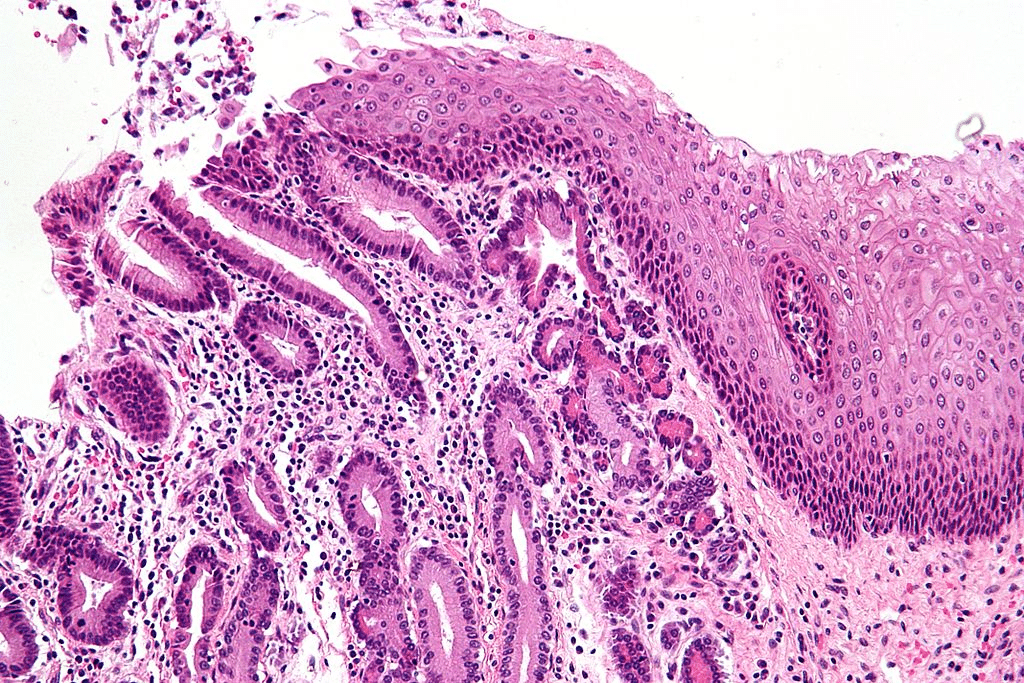

Metaplasia is the abnormal reversible change of one cell type to another. In Barrett’s oesophagus, the normal stratified squamous layer of the oesophagus is replaced by simple columnar (glandular) epithelium (as present in the stomach) (Fig. 2).

The vast majority of cases are caused by chronic gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. The epithelium of the oesophagus becomes damaged by the reflux of gastric contents, resulting in a metaplastic transformation. This in turn increases the risk of developing dysplastic and eventual neoplastic changes.

The distal oesophagus is the most commonly affected site, due to proximity to the gastro-oesophageal junction (GOJ). Diagnosis relies on biopsy, demonstrating the presence of simple columnar epithelium within the oesophagus.

Figure 2 – Barrett’s oesophagus at the GOJ, showing gastric metaplasia (on the left) and oesophageal stratified squamous epithelium (on the right)

Risk Factors

The risk factors for developing Barrett’s oesophagus include Caucasian ethnicity, male gender, age >50yrs, smoking, obesity, and the presence of hiatus hernia.

Investigations

Barrett’s oesophagus is a histological diagnosis. Patients who undergo upper GI endoscopy for reflux disease will have a biopsy taken of the affected oesophageal epithelium, which is sent for histological analysis for confirmation.

At endoscopy, Barrett’s oesophagus appears red and velvety in cases of Barrett’s oesophagus (Fig.1), with some preserved pale squamous islands. Its severity can be determined by both length and degree of dysplasia.

The major risk of Barrett’s oesophagus is progression to adenocarcinoma. Therefore, all patients with confirmed Barrett’s oesophagus must undergo regular endoscopy (Table 1). The frequency of this depends on the degree of dysplasia identified by the biopsies (if any).

|

Histology |

Endoscopy |

Comments |

| No dysplasia | Every 2 to 5 years | |

| Low grade dysplasia | Every 6 months | Repeat endoscopy with quadrantic biopsies every 1cm |

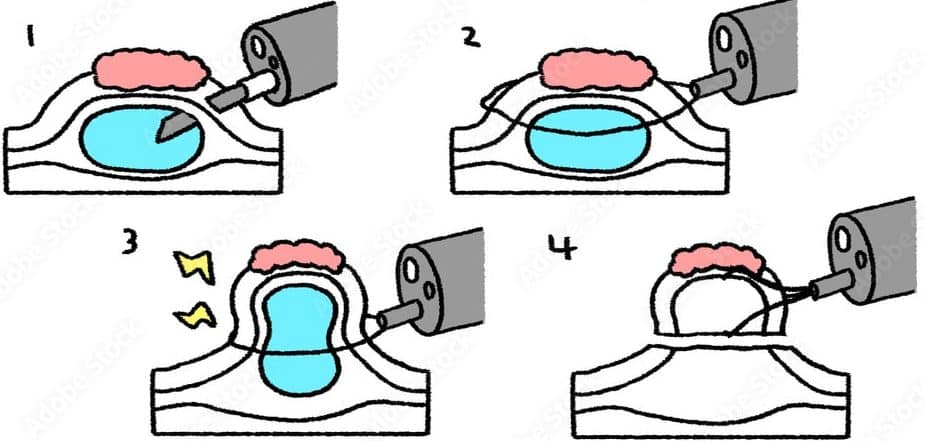

| High grade dysplasia | Every 3 months | If a visible lesion is present, endoscopic ablation with mucosal resection (EMR) |

Table 1 – Example timetable of surveillance endoscopy needed for Barrett’s oesophagus

Management

All patients with Barrett’s oesophagus must be commenced on a regular proton-pump inhibitor. Smoking cessation and reducing alcohol intake should be encouraged, and any medication that worsens reflux stopped if possible.

Surveillance is the mainstay of management for the majority of cases. However, cases of Barrett’s oesophagus with high grade dysplasia (or Barrett’s-related adenocarcinoma confined to the mucosa) should be resected typically with endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR, Fig. 3).

Figure 3 – Schematic demonstrating endoscopic mucosal resection

Key Points

- Barrett’s oesophagus is a metaplasia of the oesophageal epithelial lining

- It is a histological diagnosis, where biopsies are taken at endoscopy

- Severity is determined by length and degree of dysplasia

- Most cases will just undergo surveillance endoscopy, however higher grade lesions may warrant endoscopic mucosal resection