Introduction

Fat embolism syndrome is a rare but serious complication, occurring with the introduction of fatty tissue into systemic circulation. Whilst this is most commonly associated with long bone fractures, it can also developing following routine orthopaedic procedures or (rarely) non-traumatic causes.

Fat embolism syndrome (FES) describes the clinical sequela that occurs once fat enters the systemic circulation, with an identifiable clinical pattern of symptoms and signs.

The incidence for fat embolism syndrome is likely to be under-diagnosed, as its symptoms are non-specific (see below), with its incidence reported in the literature between 1-11%. It is likely that almost all long bone fractures introduce some element of fatty tissue into circulation, although only a small amount of these patients will develop the syndrome.

Pathophysiology

There are two main suggested theories for the formation of fat emboli:

- Mechanical theory – Fatty tissue is directly released into the vascular circulation as a result of trauma

- Biochemical theory – Inflammatory response to the trauma causes release of free fatty acids into the venous system from the bone marrow

The fatty emboli cause a severe inflammatory response in the local tissue. The inflammatory response increases vessel permeability and can lead to complications such as cerebral oedema and ARDS.

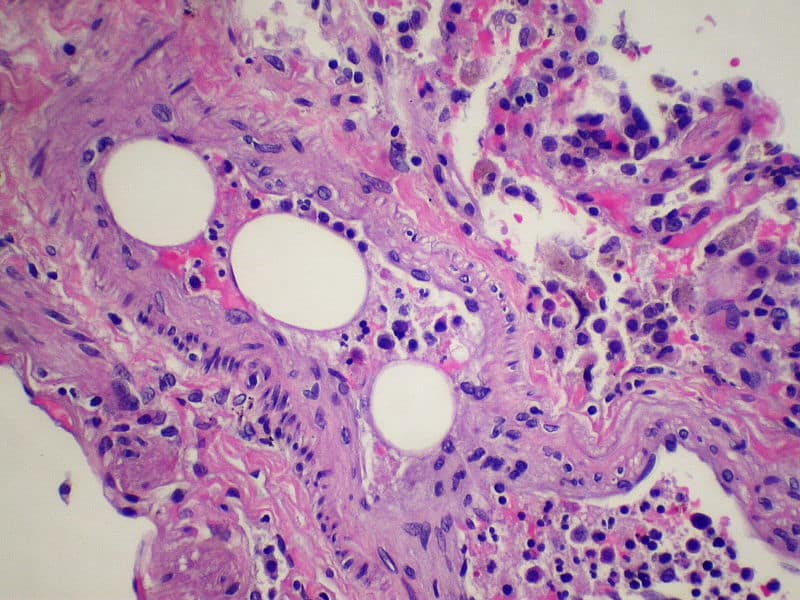

Figure 1 – Histology showing a pulmonary blood vessel containing a fat globule

Risk Factors

Known risk factors for FES include young age, long bone fractures, closed fractures or multiple fractures, and conservative management for long bone fractures

Clinical Features

Classically patients will present following trauma within the previous 24-72 hours. The most common presenting features is worsening shortness of breath, however other symptoms include confusion, drowsiness, or the development of a petechial rash (Fig. 2, classically seen in the axilla and conjunctivae).

On examination, patients will be tachypnoeic, tachycardic, and hypoxic. Often neurological signs that develop are non-specific, including acute confusion or seizures. A low grade pyrexia can also occur. In late stages of the disease, features of organ dysfunction will develop.

Gurd’s Criteria

Gurd’s criteria can be used for the diagnostic aid for fat embolism syndrome. The presence of 2 Major or 1 Major + 4 Minor criteria is deemed diagnostic

- Major criteria = Petechial Rash, Respiratory Insufficiency, Cerebral Involvement

- Minor criteria = Tachycardia, Pyrexial, Retinal Changes, Jaundice Thrombocytopaenia, Anaemia, Raised ESR, Fat macroglobulinaemia

Differential Diagnosis

The main differential for FES is pulmonary embolism, however the presence of a petechial rash in the presence of impaired cognition also raises the suspicion of a meningococcal septicaemia.

Investigations

All patients with suspected FES should undergo routine bloods, including FBC, CRP, U&Es, LFTs, and a clotting screen. An ABG will most typically show a type 1 respiratory failure. A blood film may show the presence of fat globules.

Plain film chest radiographs (CXR) will classically show diffuse bilateral pulmonary infiltrates. However often patients will undergo a CT pulmonary angiogram (CTPA) scan, showing ground-glass changes with a global distribution

Management

Management for FES is largely supportive*. The most common causes of morbidity due to fat embolism is from the respiratory sequelae, such as ARDS, therefore respiratory support is the mainstay of management; patients with severe FES will often require mechanical ventilation.

*No specific medication, including steroids, have been shown to be definitively effective to treat FES

Prevention

The prevention of FES in trauma injuries is mostly related to limiting the dispersion of bone marrow into the blood stream. This can be done by ensuring that long bone fractures are fixed as early as possible post-injury.

Patients undergoing intramedullary nailing have higher risk of developing FES, therefore close monitoring for these patients is required. Continuous pulse oximetry in high risk patients is recommended, however the use steroids in preventing the onset of FES is less well-defined.

Prognosis

The prognosis is highly dependent on the patients physiological status. Patients with advanced age and multiple co-morbidities have significantly worse outcomes. The overall mortality rate from FES is estimated to be 5-15%

Key Points

- Fat embolism syndrome (FES) is a rare but serious complication, occurring with the introduction of fatty tissue into systemic circulation

- Most commonly occurs following trauma, specifically long bone fractures

- Clinical features include shortness of breath, confusion, drowsiness, and a petechial rash

- Management is largely supportive, as there is no definitive treatment of the condition

- The overall mortality rate from FES is estimated to be 5-15%