Introduction

Oesophageal cancer is the 8th most common cancer worldwide, with over 600,000 new cases diagnosed each year. It has an incidence rising faster than any other solid organ tumour and is three times more common in men.

There are two main types of oesophageal cancer:

- Squamous cell carcinoma – more common in low and middle income countries, typically occurring in the middle and upper thirds of the oesophagus

- This subtype is more associated with smoking and excessive alcohol consumption (other risk factors include chronic achalasia, low vitamin A levels and, rarely, iron deficiency)

- Adenocarcinoma – more common in high income countries, typically occur in the lower third of the oesophagus, and arises as a consequence of metaplastic epithelium (termed Barrett’s oesophagus) which progresses to dysplasia, to eventually become malignant

- Risk factors for this subtype are long-standing GORD, obesity, and high fat intake

Other rare subtypes of oesophageal malignancy include leiomyosarcoma, rhabdomyosarcoma, or lymphoma.

Clinical Features

Early stage oesophageal cancer often lacks well-defined symptoms, which may account for the majority of patients presenting in the later course of the disease.

Dysphagia is a common presenting symptom of oesophageal cancer. progressive in nature (classically this starts with solids only, before affecting liquids). Patients may also report significant weight loss, due to both dysphagia and cancer-related anorexia. Other less common symptoms include odynophagia or hoarseness.

On clinical examination, patients may have evidence of recent weight loss or cachexia, signs of dehydration, supraclavicular lymphadenopathy, or any signs of metastatic disease (such as jaundice, hepatomegaly, or ascites)

Criteria for Upper GI Endoscopy

Current NICE guidance states the red-flag symptoms for a suspected oesophageal malignancy requiring urgent endoscopy are:

- Any patient with dysphagia

- Any patient >55yrs with weight loss and upper abdominal pain, dyspepsia, or reflux

Differential Diagnosis

There are many causes for dysphagia. Importantly, the dysphagia should be classified as either a mechanical or neuromuscular disorder, as this can significantly affect future investigations.

However, any patient presenting with dysphagia should be assumed to have oesophageal cancer until proven otherwise, therefore most patients will have an upper GI endoscopy as first line investigation.

Investigations

Any patient with a suspected oesophageal malignancy should be offered urgent upper GI endoscopy (i.e. an oesophago-gastro-duodenoscopy, OGD).

Any malignancy seen on OGD (Fig. 2) should be biopsied and the specimen sent for urgent histology to confirm the diagnosis. For patients who are not fit for endoscopy can have a CT neck and thorax scan, however this is much less sensitive and specific

Figure 2 – Oesophageal cancer, as seen on upper GI endoscopy

Further Investigations

Once the diagnosis is confirmed, further staging investigations are required to help plan treatment:

- CT Chest-Abdomen-Pelvis and PET-CT scan are used together to investigate for distant metastases

- Endoscopic ultrasound to measure the penetration into the oesophageal wall (T stage) and assess and biopsy suspicious mediastinal lymph nodes

- Staging laparoscopy (for junctional oesophageal tumours) to assess for intra-peritoneal metastases

Any palpable cervical lymph nodes may be investigated via Fine Needle Aspiration (FNA) biopsy and any hoarseness or haemoptysis may also warrant investigation via bronchoscopy.

Management

The management of oesophageal cancer should be determined by the multidisciplinary team (MDT), with input from general surgeons, oncologists, specialist nurses, nutritionists, and, if required, the palliative care team.

However, the majority of patients with oesophageal cancer will present with advanced disease and will therefore receive palliative treatment only.

Curative Management

The choice of curative treatment strategy will depend on tumour type, tumour stage, tumour site, and patient factors (such as general fitness and co-morbidities).

For those with deemed resectable disease, curative management comprises surgical or endoscopic resection, with or without neoadjuvant chemotherapy or chemo-radiotherapy:

- Squamous cell carcinoma – mainly in the upper oesophagus therefore technically difficult to operate on, however are sensitive to chemoradiotherapy and therefore definitive chemo-radiotherapy is therefore usually the treatment of choice*

- A small subgroup of early stage SCCs may be amenable to endoscopic resection

- Adenocarcinomas – the treatment of choice is typically neoadjuvant chemotherapy or chemoradiotherapy, followed by surgical resection (discussed below)

- Early stage adenocarcinomas that are small, have no lymphovascular invasion, and do not have poorly differentiated histology can be resected endoscopically

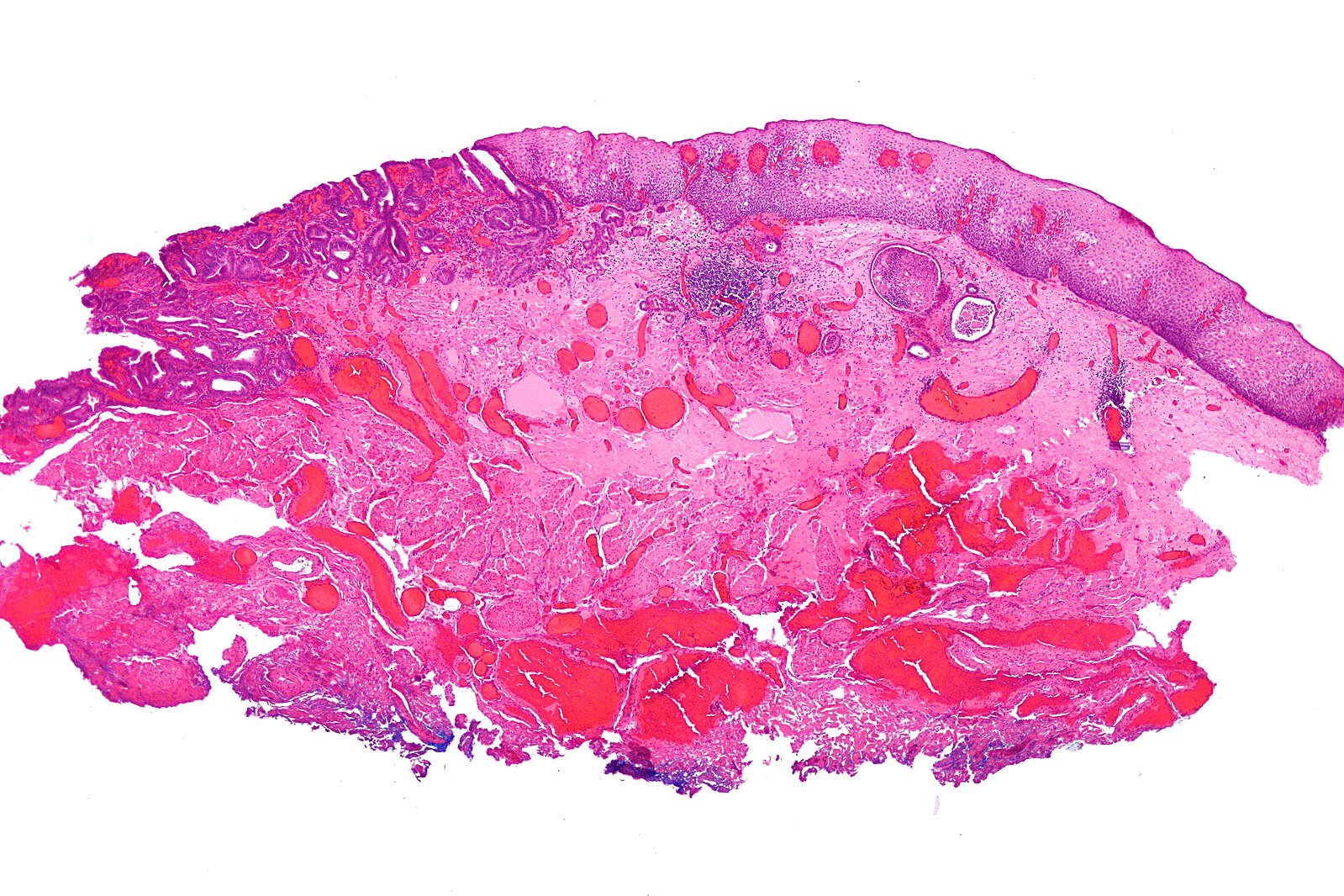

Endoscopic resection can be broadly divided to endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) or endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR, Fig. 3). ESD allows for en-bloc resection of larger lesions with lower recurrence rates but is technically more demanding with higher complication rates, whilst EMR may result in piecemeal resection in larger lesions and incomplete resections.

*Studies have shown that surgery confers no additional survival benefit compared to continuation of additional chemoradiotherapy in SCC oesophageal malignancies

Figure 3 – Histological specimen of an oesophageal adenocarcinoma following EMR

Surgical Treatment

Surgical treatment is a major undertaking, as both the abdominal and chest cavities need to be accessed, with one lung deflated for a significant proportion of the surgery.

The main surgical procedure for oesophageal cancer is an oesophagectomy. This may be as a partial or total oesophagectomy +/- partial gastrectomy. Following resection, the residual stomach is brought into the chest cavity (termed a conduit) and anastomosed proximally to allow for continuity of the GI tract. Many centres will routinely insert a feeding tube into the small bowel (a “feeding jejunostomy”) to aid nutrition post-operatively.

The procedure can be performed as open surgery or as minimally invasive surgery (either laparoscopically or robotically). Multiple open approaches can be performed:

- Right thoracotomy with laparotomy (termed an Ivor-Lewis procedure or a two-stage oesophagectomy)

- Right thoracotomy with abdominal and neck incision (termed a McKeown procedure or a three-stage oesophagectomy)

- Left thoraco-abdominal incision (one large incision starting above the umbilicus and extending round the back to below the left shoulder blade)

Post-operative nutrition is a major problem for these patients as they lose the reservoir function of the stomach. The feeding jejunostomy can support recovery, however most patients will need to eat 5-6 small meals per day to meet their nutritional requirements.

The main complications are anastomotic leak (8%), pneumonia (30%), and mortality (30 day rates around 4%).

Palliative Management

Those patients with metastatic tumours, with non-metastatic unresectable tumours, or too unfit for curative therapy can be offered a range of palliative options.

Patients with difficulty in swallowing should have an oesophageal stent placed where possible (Fig. 4). Radiotherapy, chemotherapy, or immunotherapy can be trialled for control of the disease, as well as reducing tumour size or bleeding, temporarily improving the patient’s symptoms.

Nutritional support is essential for this patient group, as progression of the disease can lead to significant dysphagia and cachexia. Thickened fluid and nutritional supplements should be offered (usually via the nutrition team). If dysphagia becomes too severe to tolerate enteral feeds, a Radiologically-Inserted Gastrostomy (RIG) tube may need to be inserted.

Prognosis

The prognosis for oesophageal cancer is generally poor due to late presentation. Palliative treated patients have a median survival of 4 months. Overall, 10 year survival rates for oesophageal cancer is 10-15%.

Key Points

- Any patient with new-onset dysphagia should be assessed for oesophageal cancer

- The gold standard investigation for any suspected case is with upper GI endoscopy (OGD)

- Only a small proportion of oesophageal cancers are suitable for surgical intervention

- The aims of treatment in the majority of cases not suitable for resection will be slowing of disease progression and symptomatic management

- Surgery is a large undertaking with significant morbidity and complication rates