Introduction

A traumatic spinal cord injury (TSCI) is traumatic injury leading to damage of the spinal cord, resulting in temporary or permanent change to neurological function, including paralysis.

TSCIs are more common in males, and the majority are due to preventable causes such as falls (40%), road traffic collisions (35%), or sport injuries (12%).

TSCI can be classified* as complete or incomplete:

- A complete injury is damage occurring across the whole spinal cord width, leading to complete loss of sensation and paralysis below the level of injury

- An incomplete injury is the injury is spread across part of the spinal cord thereby only partially affecting sensation or movement below the level of injury

*The AOSpine Injury Classification System is an internationally-recognised classification system for traumatic spinal injuries that incorporates characteristics of spinal fractures and helps guide clinical decision making regarding treatment

Pathophysiology

Trauma causes injury to the spinal cord from (1) the initial acute impact, resulting in a concussion on the spinal cord (2) compression on the spinal cord from increased pressures from nearby rigid structures (such as vertebrae and discs) that may have been displaced by the injury.

In the latter cases, such changes result in increased tissue pressure, which can block venous return and result in oedema around the spinal cord. Arterial blood supply to the spinal cord can also be compromised, and therefore lead to ischaemia. Hypoxia and ischaemia of the spinal cord leads to damage to nerves, termed gliosis.

Based on pathophysiology, spinal cord injuries can be classified into primary or secondary injuries. Primary injury refers to the destructive forces that directly damage the neural structures, such as the shear forces tearing an axon or the direct compressive force occluding a blood vessel, resulting in ischaemia. Secondary injury refers to a cascade of vascular, cellular, and biochemical events which occur following the injury, which can worsen a concurrent primary injury.

Clinical Features

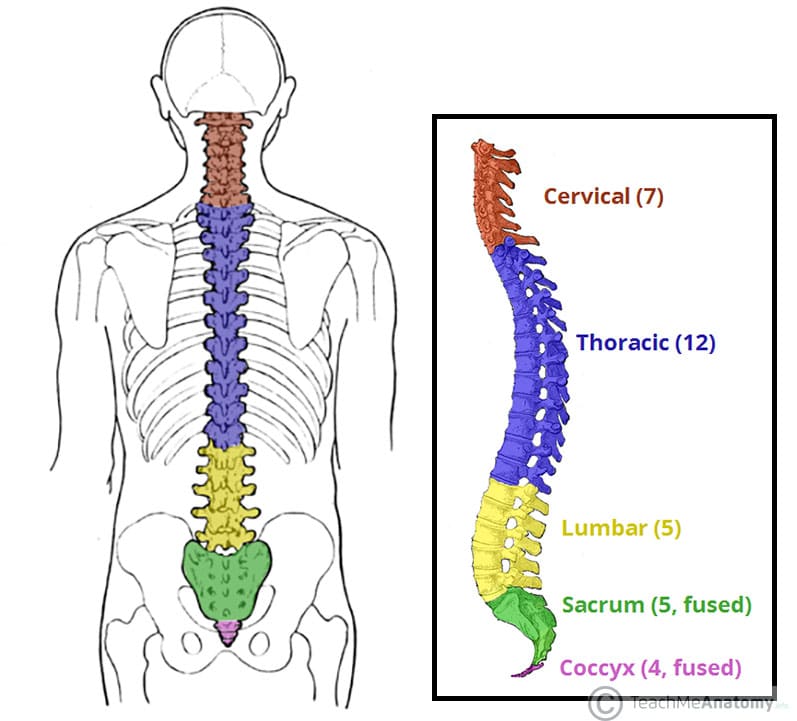

Clinical features depend on the level and completeness of injury, and around 10% of traumatic spinal injuries will result in tetraplegia or paraplegia. Pain may not be present in every case.

Clinical signs can include loss of motor function, loss of sensory function, bowel incontinence, or urinary incontinence. The ASIA Impairment Scale (Table 1) can be used to classify the degree of injury to the spinal cord following spinal injury.

|

Grade |

Type | Description |

|

A |

Complete | No motor or sensory function is preserved in the sacral segments S4–S5 |

|

B |

Sensory incomplete | Motor function is not preserved below the neurological level and includes the sacral segments S4-S5; sensory function is preserved |

|

C |

Motor incomplete | Motor function is preserved below the neurological level; more than half of key muscles below the neurological level have a muscle grade less than 3 |

|

D |

Motor incomplete | Motor function is preserved below the neurological level; at least half of key muscles below the neurological level have a muscle grade of 3 or more |

|

E |

Normal | Motor and sensory function are normal |

Table 1 – American Spinal Injury Association (ASIA) Impairment Scale

Investigations

All trauma patients first require an A to E assessment, as per the ATLS guidelines. The cervical spine must be immobilised as a priority in cases of trauma with a suggestive mechanism of injury, prior to any further examination or imaging of the region as a precaution.

Canadian C-spine rules can help further stratify risk of cervical spine injury and therefore potential imaging modality.

Canadian C-spine Rules

The Canadian C-spine rules can be used to stratify the risk of cervical spine injury following trauma and therefore aid in deciding any imaging modalities required.

The rules apply to patients who are alert (Glasgow Coma Scale score 15/15) and are in a stable condition following trauma where C-spine injury is a possibility.

Patients who have a high-risk factor require immediate radiological imaging, which includes either age ≥ 65yrs, a dangerous mechanism, or paraesthesia in extremities.

If none of these are present, those who have a low-risk factor present do not require radiological imaging prior to assessment. These factors include those involved in a simple rear-end motor vehicle collision, those who are waiting in a sitting position, those ambulatory at any time, presence of delayed onset neck pain, or the absence of midline C-spine tenderness.

An assessment of range of motion can then be carried out, if imaging deemed not required. This thorough assessment process allows appropriate stratification of trauma patients for necessary imaging.

NICE guidelines suggest the following imaging modalities following trauma to assess for potential traumatic spinal cord injuries*:

Suspected Cervical Spine Injury

- Perform a CT scan in adults, if suggested by Canadian C-spine rules

- Perform MRI for children, if suggested by Canadian C-spine rules

- Consider a plain film radiograph in those who do not fulfil the criteria for MRI but clinical suspicion remains after repeated clinical assessment

Suspected Thoracic or Lumbosacral Spine Injury

- Perform a plain film radiograph as the first‑line investigation for those with suspected spinal column injury without abnormal neurological signs or symptoms

- Perform a CT scan if the radiograph is abnormal or there are clinical signs or symptoms suggestive of a spinal column injury

- If a new spinal column fracture is confirmed, image the rest of the spinal column

*Whole body imaging should be considered with blunt major trauma and suspected multiple injuries

Management

Patients must be managed as per ATLS guidelines for any cases with suspected traumatic spinal cord injury, including the 3 point C-spine immobilisation.

Restricting movement of the spine is recommended to prevent further damage to the spinal cord, with the patient is initially strapped to a backboard prior to further assessment or imaging. Once initially stabilised, ensure appropriate pain management. Regular neurological observations should be made.

Not all traumatic spinal injuries will require surgery. Patients should be discussed with the neurosurgical or spinal team with regards to future management.

Decision-making is often guided by considering the displacement, stability, and associated neurological deficit of the injury; in the absence of neurological deficit, displacement and instability, most patients can be managed conservatively.

Conservative management includes a combination of bed rest, cervical collars, motion restriction devices, and traction, followed by early mobilisation and rehabilitation.

Surgical Management

The absolute indications for surgical management of a traumatic spinal cord injury are evidence of a progressive neurological deficit or a dislocation-type injury to the spinal column (displaced and unstable)

- Cervical spine surgery aims to realign the spine, decompress the neural tissue, and stabilise the spine with internal fixation (screws, plates, cages)

- Thoracolumbar spine surgery typically involves spinal decompression, discectomy, spinal fixation, or spinal cord simulation

Studies have shown earlier surgical intervention (within 24 hours) is associated with better outcomes.

Physiotherapy and other specialist therapy input (e.g. speech and language or occupation therapy) should be utilised early (as soon as deemed safe), as TSCI patients often require extensive rehabilitation both as inpatient and outpatient. Goals of therapy need to be discussed with the patient, to build a realistic rehabilitation plan.

Key Points

- Spinal cord injury can occur for a variety of reasons. Trauma is the most common cause

- Clinical features depend on the site of injury, and damage can be motor, sensory, or both

- The need for imaging can be established via the Canadian C Spine Rule. If imagining is required, plain X-ray, CT scans or MRI scans can all be used

- Management is not always surgical. However, if surgical intervention is required, early intervention is vital

- People who have suffered from traumatic spinal cord injury usually need extensive rehabilitation both in and out with the hospital