Introduction

Clavicle fractures are common injuries, accounting for around 3% of all fractures. They most commonly occur in adolescents and young adults, however a second peak in incidence also occurs over the age of 60, associated with the onset of osteoporosis.

Clavicular fractures can be classified by the Allman classification system, determined by the anatomical location of the fracture along the clavicle:

- Type I – fracture of the middle third of the clavicle, constituting 75% clavicular fractures (as the middle third is the weakest segment)

- They are generally stable, although significant deformity is usually present

- Type II – fractures involving the lateral third of the clavicle and constituting around 20% of all clavicular fractures

- When displaced, this type are often unstable

- Type III – remaining 5% occur in the medial third of the clavicle, commonly associated with multi-system polytrauma

- As the mediastinum sits directly behind the medial aspect of the clavicle, they can be associated with neurovascular compromise, pneumothorax, or haemothorax

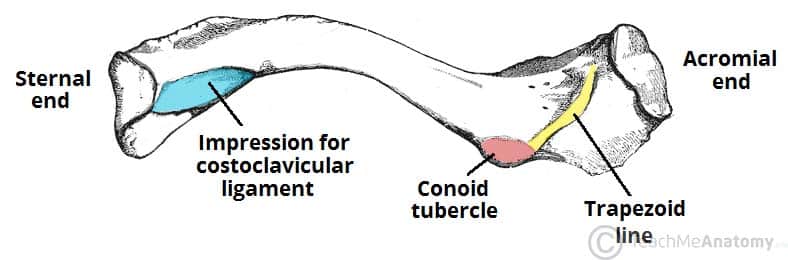

Pathophysiology

Clavicle fractures will occur through either a direct (trauma directly onto the clavicle) or indirect (such as a fall onto the shoulder) mechanism of injury.

The medial fragment will often displace superiorly, due to the pull of the sternocleidomastoid muscle, whilst the lateral fragment will displace inferiorly from the weight of the arm.

Clinical Features

Patients will present with sudden-onset localised severe pain, made worse on active movement of the arm, nearly always following trauma. On examination, there will be focal tenderness, with deformity and mobility at the fracture site.

Due to the subcutaneous location of the clavicle, it is important to specifically look for open injuries or threatened skin (appearing as tented, tethered, white, and non-blanching skin); it is essential that any threatened skin is recognised as it implies impending conversion to an open injury.

Ensure to check the neurovascular status of the upper limb, given the propensity for brachial plexus injuries following a clavicle fracture. Also check for surgical emphysema, which may indicate a pneumothorax.

Differential Diagnoses

Whilst the diagnosis is often apparent, differentials to consider include sternoclavicular dislocation and acromioclavicular joint (ACJ) separation.

Investigations

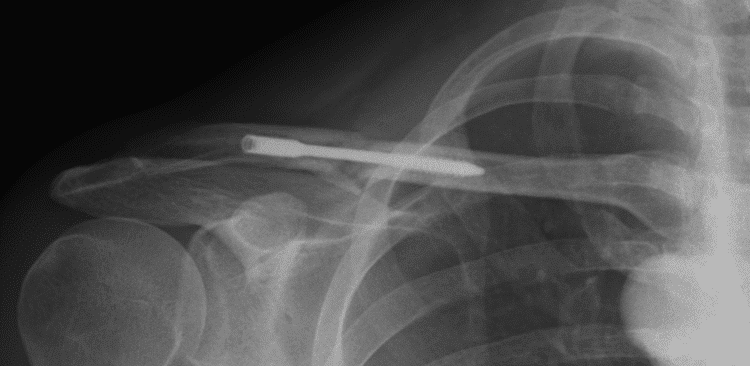

Plain film anteroposterior and modified-axial radiographs of the affected clavicle should be performed (Fig. 2), allowing any displacement to be fully assessed.

CT imaging is rarely indicated, but may be needed to assess medial clavicle injuries, which can be difficult to fully assess on plain radiographs.

Management

Most clavicle fractures can be treated conservatively, even those with significant deformity, as evidence has shown no long-term benefit to surgical management over a conservative approach, with >90% uniting despite displacement*. As the clavicle is subcutaneous, metalwork is often prominent and therefore may require removal after fracture union too

Initial treatment is with a sling, which should be properly applied so that the elbow is well supported and improves the deformity. Early movement of the shoulder joint is recommended, to prevent the development of frozen shoulder in these patients. The sling is generally kept on until the patient regains pain-free movement of the shoulder.

Fractures of the proximal clavicle will also need to be considered in the wider context of associated injury, such as traumatic pneumothorax, and managed accordingly.

*Patients should be given the option of operative management (in appropriate cases) because a potential shorter time to union may be worth the risks of surgery in certain patients (e.g. self-employed).

Surgical Management

All open fractures will need surgical intervention. However, surgical management for the remainder of clavicle fractures remains contentious. It is usually reserved for very comminuted fractures or those that are very shortened. It is also typically performed if the patient has bilateral fractures, to permit weight bearing.

Where fractures have failed to unite, an open-reduction internal-fixation (ORIF) will be necessary, which is usually performed at 2-3 months post-injury.

Prognosis

Non-union is a major complication of clavicle fractures, most associated with a distal third clavicular fractures. Other important complications to assess for include neurovascular injury and any puncture injury (haemothorax or pneumothorax). Healing time for most clavicular fractures in adults is 4-6 weeks.

Key Points

- Fractures typically occur in the middle third of the clavicle

- Plain film radiographs, both anteroposterior and modified-axial views, are required to assess suspected cases

- Most clavicle fractures can be treated conservatively

- Non-union is a major complication of clavicle fractures