Introduction

Anal cancer is a relatively rare cancer of the gastrointestinal tract, accounting for around 4% of colorectal cancers and has a UK incidence of approximately 1 in 100,000.

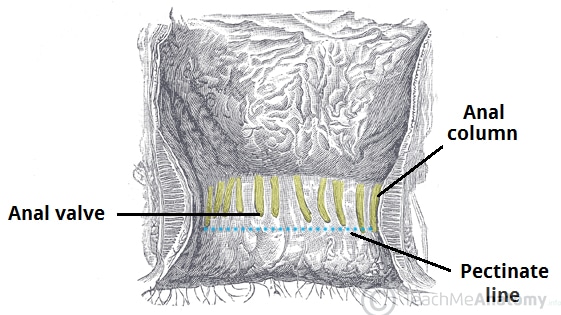

The majority of anal cancers are squamous cell carcinomas, arising from below the dentate line (Fig. 1). The remainder (~10%) are adenocarcinomas arise from the upper anal canal epithelium and the crypt glands. Less common anal tumours include melanomas and anal skin cancers.

A pre-cancerous condition, anal intraepithelial neoplasia (AIN), may precede the development of invasive squamous anal carcinoma.

Anal Intraepithelial Neoplasia

Anal intraepithelial neoplasia (AIN) is a precancerous condition that can affect either the perianal skin or anal canal, linked to the development of squamous cell carcinoma. It is strongly linked to infection with the human papilloma virus (HPV).

The grading of AIN is dependent on the degree of cytological atypia and the depth of that atypia in the epidermis. High-grade AIN (grade 2 or 3) is premalignant and may progress to invasive cancer.

Risk Factors

The risk factors for developing anal cancer include HPV infection (accounts for 80-90% of cases, especially HPV-16 and HPV-18), HIV infection, increasing age, smoking, immunosuppression, or Crohn’s disease.

Clinical Features

The main symptoms of anal cancer are rectal pain or rectal bleeding, occurring in around half of patients. Other symptoms may include anal discharge, pruritus, or the presence of a palpable mass.

Recurrent perianal infection can be seen in locally invasive disease. If the anal sphincters have been involved, faecal incontinence and tenesmus can also occur.

On examination, the perineal and perianal regions should be screened for any ulceration or the presence of wart-like lesions. Any mass felt on PR exam should be documented along with its distance from the anal verge and the proportion of anal circumference involved.

The inguinal lymph nodes should be examined for any lymphadenopathy*.

*Lymph from the area below the dentate line drains to the superficial inguinal nodes, whereas the anal canal and rectum above the dentate line drain into the mesorectal, para-aortic, and paravertebral nodes.

Differential Diagnosis

The main differentials for an anal cancer include thrombosed haemorrhoids, anal warts, low rectal cancer, or skin cancer.

Investigations

Initial Investigations

Following initial examination, proctoscopy should be performed to obtain a better initial assessment of the anal canal. All patients with suspected anal cancer should then undergo examination under anaesthetic (EUA) of the rectum.

An EUA rectum allows for much better assessment for tumour size and invasion of local structures, as well as allowing a biopsy to be taken for histological confirmation.

In women, a smear test may be necessary to exclude any cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) and any further biopsies if signs of vulval intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN) are present. Consider a HIV test, especially those with risk factors.

Imaging

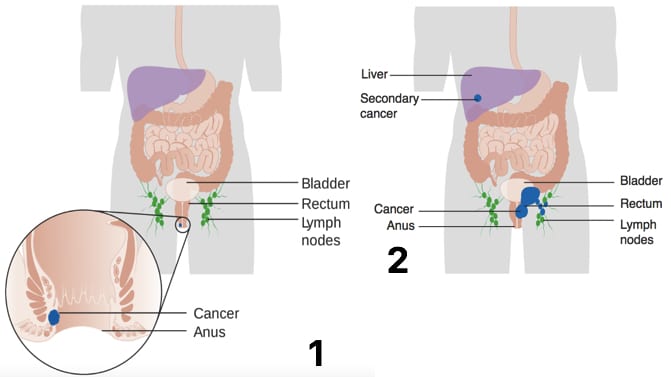

Once the diagnose has been confirmed by biopsy, further staging investigations (Fig. 3) are required:

- Ultrasound-guided Fine Needle Aspiration (FNA) of any palpable inguinal lymph nodes

- CT scan of chest-abdomen-pelvis for evidence of metastases

- MRI pelvis to assess the extent of local invasion (T stage)

Figure 3 – Diagram showing the (1) Stage 1 and (2) Stage 4 anal cancer metastasis

Management

A multidisciplinary approach must be used in the management of anal cancer, including oncologists, general surgeons, radiologists, and specialist nurses.

Chemo-radiotherapy is often the first choice treatment for anal tumours (expect from T1N0 carcinomas, whereby wide local excision surgical treatment is usually sufficient). Treatment is usually via external beam radiotherapy to the anal canal and inguinal lymph nodes, combined with dual-chemotherapy agents, such as mitomycin C and 5-fluorouracil.

Surgical Management

Surgical excision is usually reserved for management of advanced disease, after failure of chemoradiotherapy, or in early T1N0 carcinomas.

The majority of patients requiring surgical intervention for anal cancer will receive an abdominoperineal resection (APR), yet for some a posterior or total pelvic exenteration is required.

Patients should be reviewed every 3–6 months initially. Most recurrences occur in the first 3 years following surgery and will tend to relapse locally and regionally rather than have spread distant.

Complications

Chemoradiation-related pelvic toxicity is the most common short term complication, which can present with dermatitis, diarrhoea, proctitis, and/or cystitis.

Longer term, patients may develop fertility issues, faecal incontinence, vaginal dryness, erectile dysfunction, and rectovaginal fistula. Prognosis is related to the initial staging of the tumour (Table 1).

| Tumour Stage | 5 Year Survival (%) |

| I | 69.5 |

| II | 61.8 |

| IIIa | 45.6 |

| IIIb | 39.6 |

| IV | 15.3 |

Table 1 – Five year survival rates of anal cancer

Key Points

- Pain and bleeding are the most common symptoms in anal cancer

- All patients with suspected anal cancer should undergo examination under anaesthesia of the rectum

- Chemo-radiotherapy is first line curative treatment for the majority of patient