Introduction

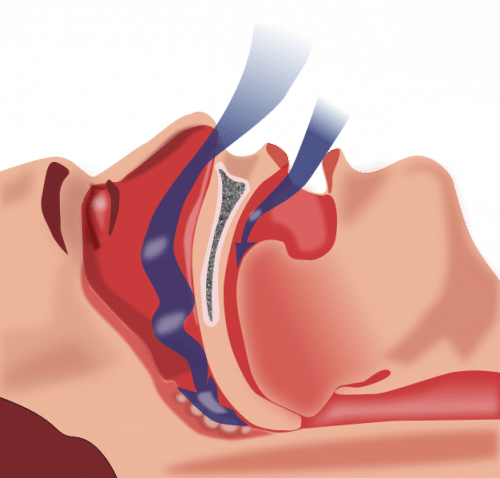

Obstructive sleep apnoea (OSA) is a clinical condition of intermittent and recurrent apnoeic or hypopnoeic episodes secondary to collapse of the upper airways during sleep.

Apnoea is defined as the complete cessation of airflow for 10 seconds, whilst hypopnoea is defined as 50% flow reduction of airflow for 10 seconds

The prevalence of the obstructive sleep apnoea is increasing worldwide, mainly due to growing obesity rates globally. Current estimates suggest that around 2% of women and 4% of men in Western countries are affected by the condition.

In this article, we shall look at the risk factors, clinical features, and management of obstructive sleep apnoea.

Risk Factors

The main risk factor associated with obstructive sleep apnoea is obesity. Other risk factors include male gender, smoking or excess alcohol, retrognathia or macroglossia, and the use of sedating drugs.

In children, due to narrower airways, tonsillar and adenoid enlargement can cause partial obstruction of the upper airways, leading to obstructive sleep apnoea.

Figure 1 – Collapse of the upper airways in obstructive sleep apnoea

Clinical Features

The main presenting features of obstructive sleep apnoea are excessive daytime sleepiness and reduced concentration. This sleeping disturbance may be observed by others, such as snoring, choking episodes, or observed apnoea.

Other less specific features can include personality changes, reduced libido, or restlessness. Ensure to to enquire about the effects of daytime sleepiness on driving, work performance, relationships, and mood, as OSA can also have a significant psychological impact on the patient. All patients should be evaluated with the Epworth Sleepiness Scale to assess the impact of OSA on the patient’s daily life.

Most patients are typically obese yet examination is usually otherwise unremarkable. Ensure to assess for any clinical features that may suggest a head and neck cancer during assessment.

Epworth Sleepiness Scale

The extent and severity of daytime sleepiness can be quantified using the Epworth Sleepiness Scale. This questionnaire asks about the likelihood of falling asleep whilst being engaged in 8 different activities during the daytime.

This scale is a score out of 24, with a score >10 indicating abnormal daytime sleepiness. Scores 11-15 suggest mild to moderate impact, whilst scores 16-24 suggest severe disease

Differential Diagnoses

The main other causes of daytime sleepiness include sleep disturbance (from anxiety or depression), narcolepsy, hypothyroidism, or medication (such as sedatives or SSRIs)

Other causes of nocturnal choking or gasping include reflux disease, nocturnal asthma, or heart failure (presenting as paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnoea or orthopnoea).

Investigations

OSA is formally diagnosed via sleep studies, the gold standard of which is typically polysomnography (PSG). PSG aims to measure the number of apnoeic or hyponoeic episodes per night, calculated as an Apnoea-Hypopnoea Index (AHI).

The AHI can then determine the severity of the OSA, defined by normal = 0-5 episodes; mild = 5-15 episodes; moderate = 15-30 episodes; severe = >30 episodes.

However, many centres do not perform PSG, as it is resource intensive and requires hospitalisation overnight. More commonly, sleep study is performed at home with the necessary equipment (yet this will not include data such as EEG readings or CO2 tracings). Simple oxygen saturation monitoring overnight can be performed to identify any desaturation episodes, although this is not a very reliable test.

Management

As most cases of obstructive sleep apnoea occur secondary to obesity, conservative management such as advice regarding lifestyle changes should be given. These include weight loss advice, increased exercise, smoking cessation, and alcohol reduction.

Non-Surgical Intervention

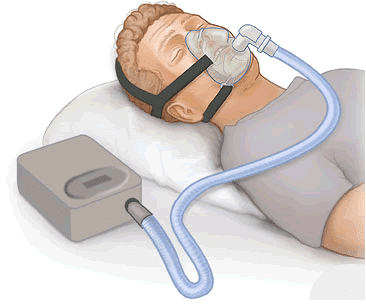

For patients with moderate to severe OSA, continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) is the first line treatment (Fig. 2). CPAP works by providing a positive pressure of air during the night to splint the airways open, preventing any further hypoxic episodes*.

However, compliance with CPAP is often quite poor due to patient discomfort and potential claustrophobia with CPAP masks. For those with mild OSA or unable to tolerate CPAP, intra-oral devices, such as a mandibular advancement device, can be trialled to varying degrees of success (such patients should be referred to oral maxillofacial surgeons for further assessment).

*Use of CPAP in severe OSA patients can significantly reduce diurnal and nocturnal blood pressure

Figure 2 – CPAP forms the basis of non-invasive OSA management

Further Management

Surgical interventions for OSA have poor evidence-based outcomes*. Surgical interventions that can be trialled include uvulopalatopharyngoplasty (UPPP), laser-assisted uvulopalatopharyngoplasty (LAUP), radiofrequency ablation of the tongue base, or suspension of the hyoid bone.

Select patients may benefit from orthognathic surgery if they have significant retrognathia. Children with tonsillar and/or adenoid enlargement resulting in OSA will significantly benefit from tonsillectomy or adenoidectomy with excellent long-term outcomes.

*There is growing evidence that transoral robotic surgery for tongue base reduction can produce good results.

Complications

Patients with obstructive sleep apnoea need to be made aware of the impact their daytime sleepiness can have, particularly on work and driving. In the UK, any patients on CPAP treatment should inform the DVLA.

Obstructive sleep apnoea can result in significant cardiovascular co-morbidity, increasing the risk of developing hypertension, ischaemic heart disease and stroke. Consequently, all patients with obstructive sleep apnoea should have their cardiovascular risk profile regularly calculated and managed accordingly. However, early treatment of obstructive sleep apnoea with CPAP has an excellent prognosis, with near normal cardiovascular function and all-cause mortality rates in treated individuals.

Key Points

- Obstructive sleep apnoea is the intermittent and recurrent apnoeic or hypopnoeic episodes, secondary to collapse of the upper airways during sleep

- Obesity is the main risk factor for developing OSA

- The gold standard for diagnosis of OSA is via polysomnography (PSG)

- The mainstay of treatment is continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP)