Introduction

Osteomyelitis is defined as an infection of bone, either acute or chronic.

In adults, the vertebrae are the most commonly affected bones, whilst in children, long bones are more commonly affected. Most cases are acute and bacterial in origin, however it can also be chronic and rarely can even be fungal in origin.

Osteomyelitis can be caused by 3 main routes:

- Haematogenous spread

- Direct inoculation of micro-organisms into the bone (e.g. following an open fracture)

- Direct spread from nearby infection (e.g. adjacent septic arthritis)

The most common causative organisms for osteomyelitis include S. aureus (most common), Streptococci, Enterobacteur spp., H. Influnzae, P. aeruginosa (especially in intravenous drug users), and Salmonella spp. (especially in patients with sickle cell disease)

Pathophysiology

Once bacteria enter the bone tissue, they express adhesins to bind to the host tissue proteins and produce a polysaccharide extracellular matrix. Through this, the pathogens are able propagate, spread, and seed further in the tissue.

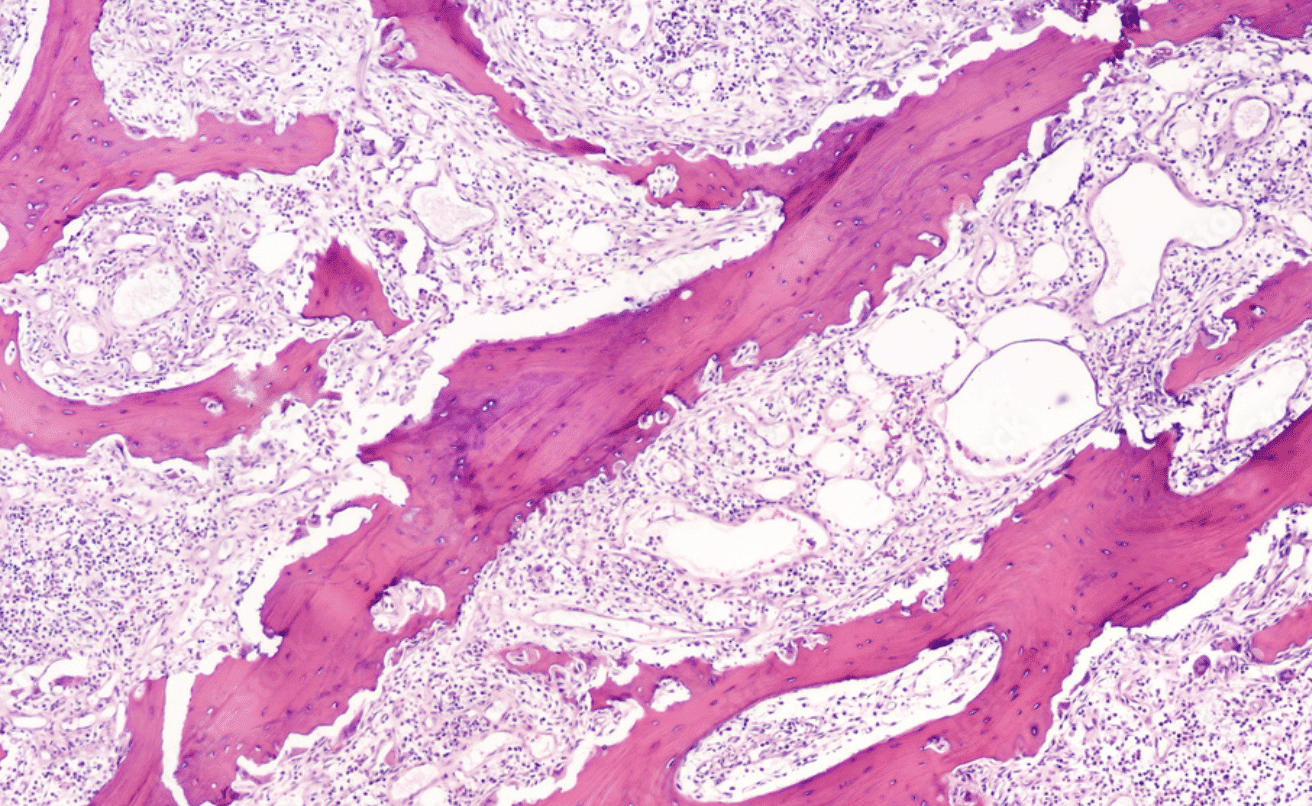

In chronic cases, the infection can lead to devascularisation of the affected bone, resulting in necrosis and resorption of the surrounding bone. This leads to a “floating” piece of dead bone, termed a sequestrum, which acts as a reservoir for infection (and cannot be penetrated by antibiotics, as it is avascular).

An involucrum can also form, following the sequestrum formation, whereby the region becomes encased in a thick sheath of new periosteal bone.

Risk Factors

Risk factors for developing osteomyelitis include diabetes mellitus, immunosuppression (such as long term steroid treatment or AIDS), alcohol excess, or intravenous drug use.

Osteomyelitis and the Diabetic Foot

Foot infections occur frequently in diabetic patients, these infections are often due to minor trauma, but due to a combination of neuropathy and small vessel disease, infection often develops quickly and can initially go unnoticed.

Soft tissue infection can therefore increase the risk of osteomyelitis developing. It is important to suspect osteomyelitis in any diabetic patient with a deep or chronic foot infection. Any suspected case should have an MRI scan to confirm the diagnosis.

Clinical Features

Patients will usually present with severe pain* in the affected region and associated low grade pyrexia. Pain is constant and can be worse at night. Cases may present with non-specific symptoms or possibly with a previous history of recent trauma.

On examination, the site will be tender, with potential overlying swelling and erythema. If the lower limb is affected, the patient may be unable to weight bear.

Ensure you examine for potential sources of the infection, such as pock marks or sinuses from intravenous drug use, cellulitic areas, penetrating wounds, or stigmata of concurrent infection in another body system.

*In patients with diabetic foot, pain may be absent due to peripheral neuropathy

Differential Diagnosis

The main differentials for suspected cases of osteomyelitis include septic arthritis, traumatic injuries (including soft tissue injury or fractures), and primary or secondary bone tumours.

Potts Disease

Potts disease is an infection of the vertebral body and intervertebral disc by Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Patients will present with back pain +/- neurological features, with associated low grade fever and non-specific infective symptoms.

The infection will initially start in the intervertebral disc before spreading to the para-discal regions, typically affecting the thoraco-lumbar region of the spine.

MRI imaging is the gold-standard investigation for suspected cases. Most cases will require a prolonged course of anti-TB medication, however surgical intervention may be required for abscess drainage in the case of extensive spinal destruction.

Investigations

Patients with suspected acute osteomyelitis require urgent blood tests, including a FBC and CRP. Blood cultures should be performed (which are positive in around 60% cases).

Plain film radiographs (Fig. 3) are often performed initially in suspected cases, although they have poor accuracy for osteomyelitis; indeed, any visible radiological signs tend to only be visible from 7-10 days post-initial infection. Potential radiographic features include osteopaenia, periosteal thickening, endosteal scalloping, and focal cortical bone loss.

Diagnosis is often achieved through MRI imaging, demonstrating bone marrow oedema as early as days 1-2 post-infection. Nuclear medicine bone scans, e.g. PET-CT or scintigraphy, may also be used in diagnosing osteomyelitis, showing evidence of any active infection.

The gold standard diagnosis of osteomyelitis is from culture via bone biopsy at debridement (or curettage where there are associated ulcers), which has >90% sensitivity. Ensure culture is checked for mycobacterium and fungal causes especially in susceptible cases, such as those who are immunosuppressed.

Figure 3 – Osteomyelitis of the 1st metatarsophalangeal joint

Management

If the patient is clinically well, patients will require long-term intravenous antibiotic therapy (>4 weeks), tailored to any cultures available or otherwise following local antimicrobial protocols. This is usually the mainstay of treatment for osteomyelitis, with no surgical intervention is needed.

However, in cases where the patient clinically deteriorates or imaging shows progressive bone destruction, then surgical management may be required. At this stage, surgical debridement of the infected bone is required, ensuring any samples are sent for culture and sensitivity. In severe or chronic cases, large debridements and complex reconstruction may be needed.

Complications

Poorly managed acute osteomyelitis may lead to sepsis and even mortality. Associated septic arthritis or soft tissue infections may occur.

Children may develop growth disturbances as a result of premature physeal closure. Amputation is rarely required in modern practice.

Recurrence of infection can occur, often associated with premature cessation of antibiotics. Chronic osteomyelitis can occur in immunocompromised patient, under-treated patients, or virulent or resistant organisms.

Chronic Osteomyelitis

Patients with chronic osteomyelitis will present with localised ongoing bone pain and non-specific infection symptoms (e.g. malaise or lethargy). There may be a draining sinus tract and they may have difficulties in mobility.

Blood tests can often show normal inflammatory markers and negative blood cultures, and positive cultures from any sinus tract are often contaminants.

Surgical management involves local bone and soft tissue debridement for definitive source control, alongside extensive long-term antibiotic therapy.

This will then likely need complex staged reconstruction with prolonged rehabilitation, which the patient should be made aware of pre-operatively; amputation may be considered in advanced cases.

Key Points

- Osteomyelitis is an infection of the bone, most commonly bacterial in origin

- Risk factors include diabetes mellitus, immunosuppression, alcohol excess, or intravenous drug use

- Patients present with severe constant localised pain, often associated with low-grade pyrexia

- Gold standard diagnosis is from culture from bone biopsy at debridement, however MRI imaging can help make the diagnosis

- Management typically requires long-term antibiotic therapy