Introduction

An aneurysm is defined as a persistent abnormal dilatation of an artery to 1.5 times its normal diameter. A thoracic aortic aneurysm can involve the ascending aorta or aortic root (60%), aortic arch (10%), descending aorta (40%), or thoracoabdominal aorta (10%) segments.

Whilst thoracic aneurysms are less common than abdominal aortic aneurysms, they are associated with high mortality. They have an incidence of 6 in 100,000 person-years, with an increasing prevalence with age.

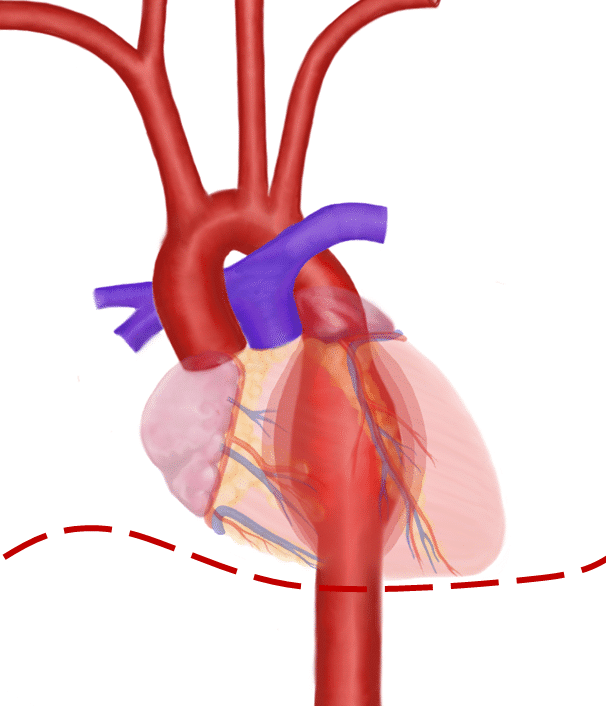

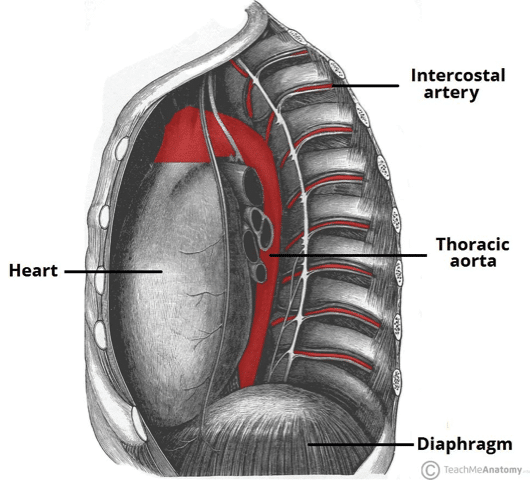

Figure 1 – Lateral view of the thoracic aorta, including the intercostal branches

Aetiology

Thoracic aortic aneurysms develop due to degradation of the tunica media, the layer of the artery which provides tensile strength and elasticity to the wall.

As a result, the artery loses structural integrity and dilates, and as the diameter increases, the wall tension rises and further increases the diameter in a vicious cycle.

The main causes of thoracic aneurysm are:

- Connective tissue diseases (e.g. Marfan’s syndrome or Ehlers-Danlos syndrome)

- Bicuspid aortic valve

Other causes include trauma, aortic dissection, aortic arteritis (e.g. Takayasu Arteritis), and tertiary syphilis

Thoracic aortic aneurysms grow at a mean rate of 1-2mm/year. This rate is higher in those with Marfan’s syndrome, descending aneurysms (compared to ascending aneurysms), and a dissected aneurysm (compared to a non-dissected).

Risk Factors

The main risk factors for developing a thoracic aortic aneurysm include family history (19% have a positive family history), hypertension, atherosclerosis (specifically descending aneurysms), smoking, high BMI, male gender, and advanced age.

Clinical Features

Typically thoracic aneurysms are asymptomatic and are found incidentally.

In those that are symptomatic, the most common presenting symptom is chest pain, depending on the location of the anuerysm:

- Ascending aorta – anterior chest pain

- Aortic arch – neck pain

- Descending aorta – posterior thoracic pain

Other symptoms of thoracic aneurysms include back pain (secondary to spinal compression), hoarse voice (from damage to the left recurrent laryngeal nerve in arch aneurysms), or clinical features of heart failure (from involvement of the aortic valve)

Clinical signs are not commonly found on examination, however chronic disease may present with the signs of aortic root disease or heart failure. Those with SVC compression from their thoracic aneurysm may present with distended neck veins

Thoracic Aneurysm Rupture

Thoracic aortic aneurysms have a risk of rupture or dissection, both of which are potentially lethal. Patients will present with sudden onset chest or back pain and present in profound hypovolaemic shock. Urgent diagnosis and surgical intervention is required, however mortality rates are high.

Differential Diagnosis

As thoracic aneurysms are mostly found incidentally on imaging, other differential diagnosis are rarely considered before the definitive diagnosis is determined.

In symptomatic patients, the scope of symptoms for a thoracic aneurysm is wide. However for those presenting with chest or back pain (the most common presentation), diagnoses of acute coronary syndrome, pulmonary embolism, pneumothorax, and aortic dissection should all be considered.

Investigations

Thoracic aneurysms are diagnosed through imaging. All patients with a thoracic aneurysm identified should have initial work-up including routine bloods (FBC, U&Es, clotting), an electrocardiogram (ECG), and a plain film chest radiograph (CXR) performed.

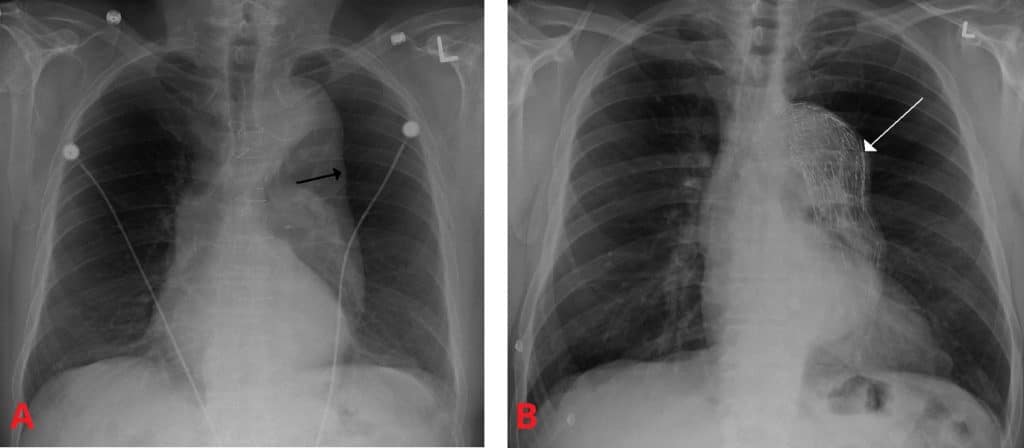

Indeed, a thoracic aneurysm can often be seen on CXR, demonstrating a widened mediastinal silhouette, an enlarged aortic knob, and possible tracheal deviation (Fig. 3). However, such plain film imaging is not sensitive enough to make the definitive diagnosis and further imaging is required

Imaging

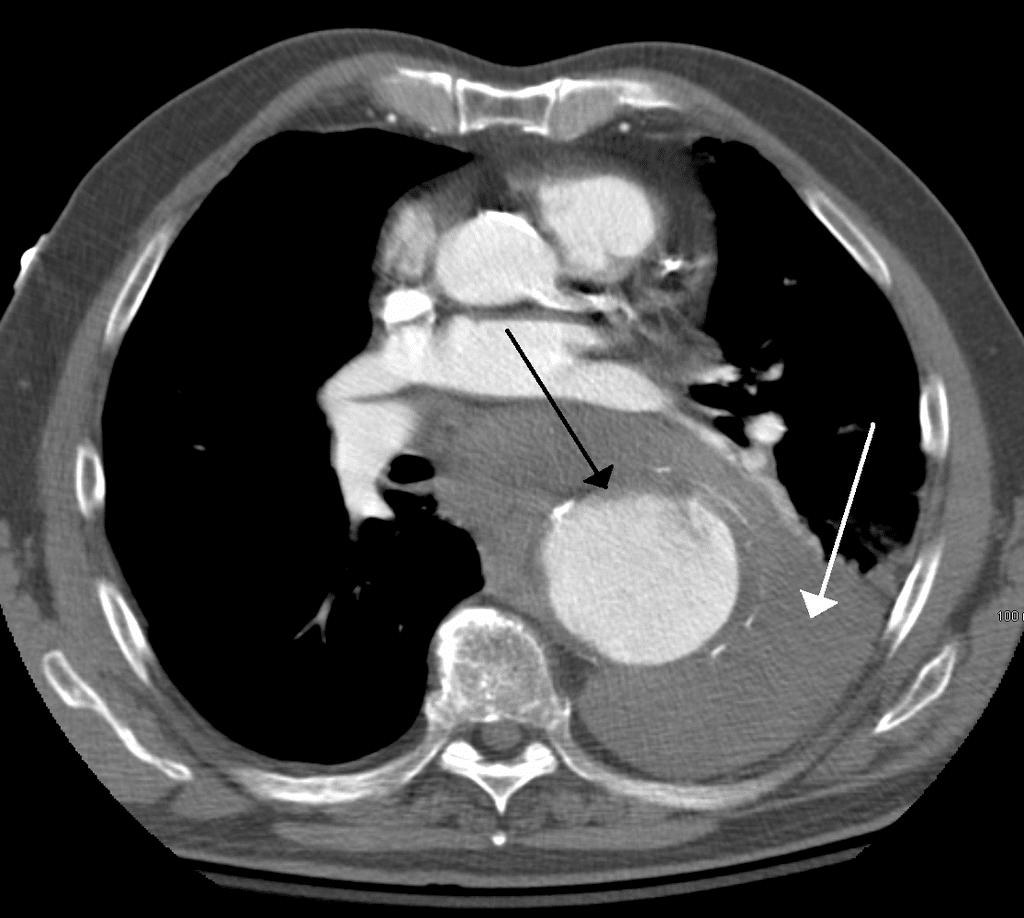

A CT angiogram (CTA) is the preferred imaging modality for thoracic aneurysms, providing sufficient detail to ascertain the level and the size of the aneurysm. CTAs can visualise the sac and the lumen, and detect any potential complications (e.g. rupture or mural thrombus). MR imaging can also be used.

Transoesophageal echocardiography (TOE) can be used to good effect to further detect any concurrent aortic insufficiency or dissection; TOE should form part of the routine assessment of patients with Marfan’s disease and suspected thoracic aortic disease.

Management

Patients with a confirmed thoracic aneurysm should be started on medical management. These patients are at increased cardiovascular risk, therefore should be initiated on statin and anti-platelet therapy to decrease the risk of myocardial infarction, blood pressure control optimise, and smoking cessation enforced (if appropriate).

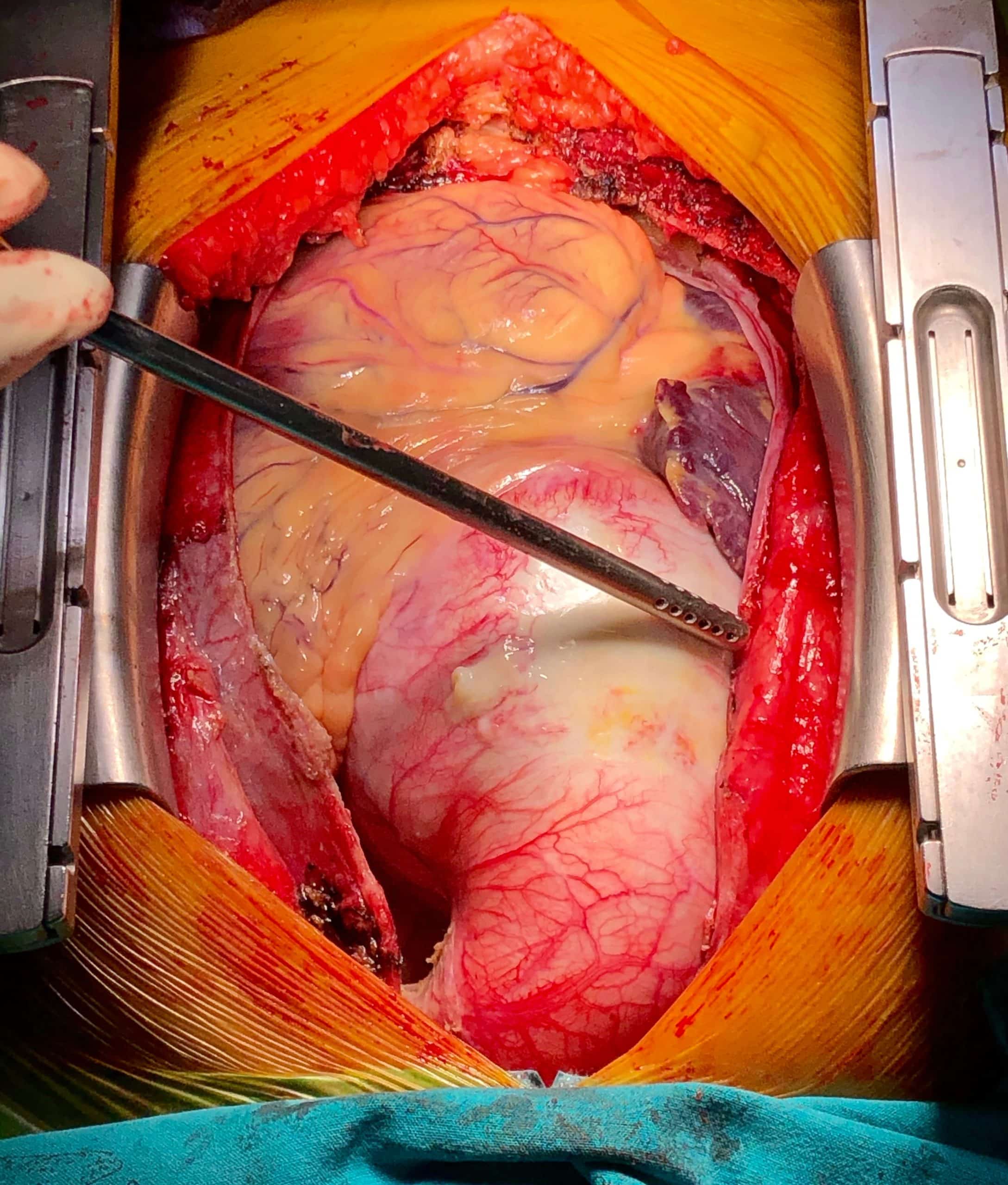

Figure 4 – An ascending aortic aneurysm, prior to open surgical repair

Surgical Management

Surgical management is dependent on the location of the aneurysm, with the threshold for surgery varying dependent on patient factors. For example, patients suffering from Marfan’s syndrome or having a previous thoracic dissection have a greater risk of dissection and rupture, and threshold levels for intervention are often lower

Whilst cut off criteria will vary, a guide to thoracic aneurysm surgical interventions can be followed:

- Ascending Aorta – Treated when the diameter >5.5cm, the affected region of the aorta is excised and replaced with a dacron graft; if the aortic root is involved, a Bentall procedure is often performed, using a graft that also contains a prosthetic aortic valve

- Aortic Arch – Once the aneurysm is over 5.5cm, surgery should be considered; the affected aorta is replaced with a multi-limbed graft, allowing for the branching of the great vessels (such procedures have a high risk of cerebral ischaemia from embolisation)

- Descending Aorta – Intervention is indicated when the diameter exceeds 6.0cm; these can be repaired open or with endovascular techniques, yet endovascular techniques have been shown to produce fewer post-operative complications and have a lower mortality

Prognosis

Development of a second aneurysm is not uncommon in these patients post-intervention, so ongoing imaging studies as an outpatient are required following surgery, either with CT or MRI imaging.

Recent studies demonstrate a perioperative mortality of between 2-17%, with arch aneurysms having the highest mortality at 25% mortality. Mortality is significantly lower in those undergoing endovascular repair.

In patients who are monitored prior to surgery, the annual risk of rupture or dissection is 2% when <5cm, 3% for 5-5.9cm, and 7% for those 6cm or above.

Figure 5 – Contrast CT scan demonstrating a 7cm thoracic aortic aneurysm (black arrow) that has ruptured; the white arrow demonstrates blood in the thorax

Key Points

- Most cases of thoracic aneurysm are associated with connective tissue disorders or bicuspid aortic valve

- Thoracic aneurysms are most often identified incidentally in routine imaging, however are best identified through CT imaging with contrast

- Management of thoracic aneurysm depends on location

- The annual risk of rupture or dissection is 2% when the aneurysm is <5cm, 3% for 5-5.9cm, and 7% for those >6cm