Introduction

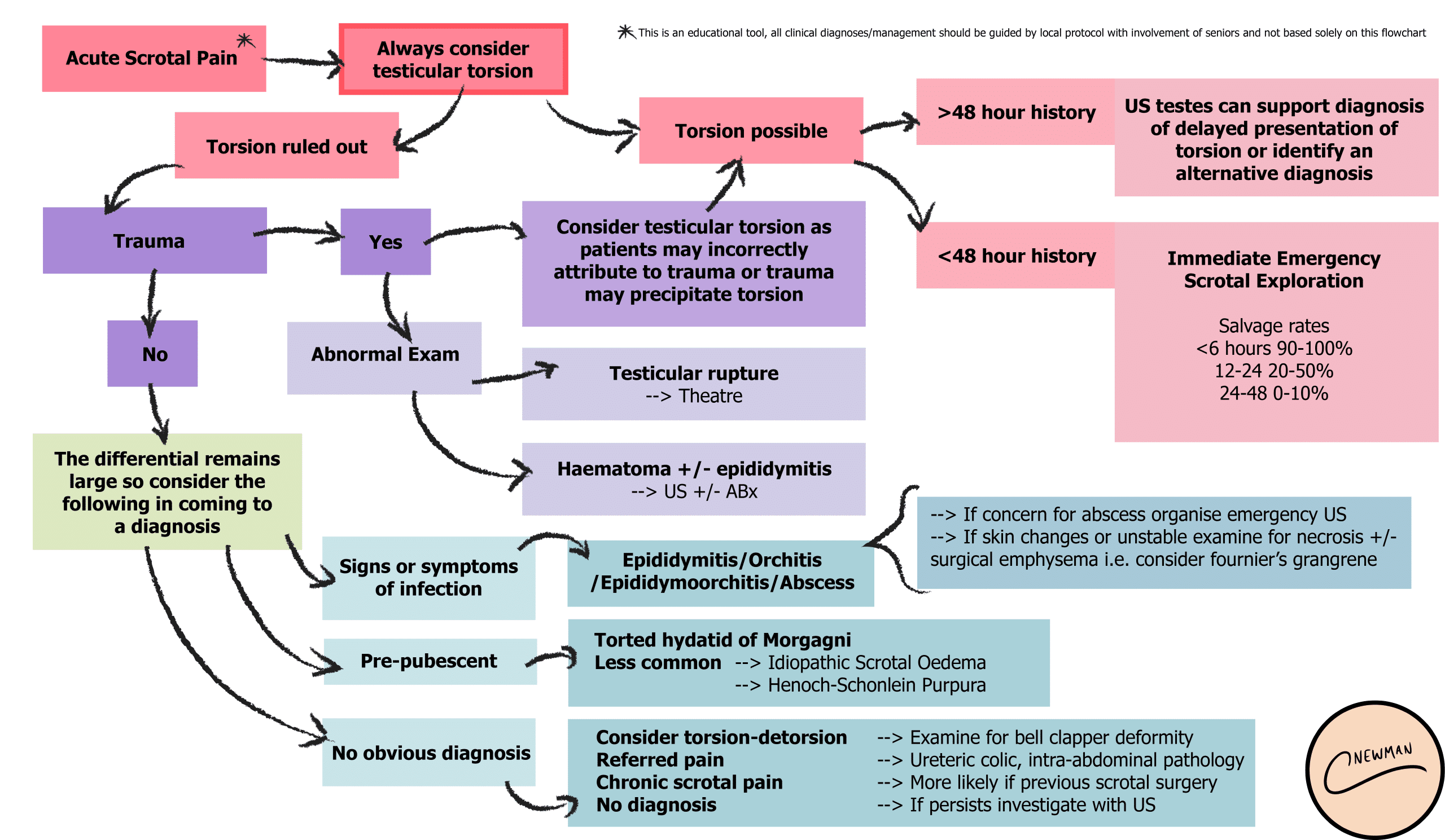

Acute scrotal pain commonly presents on unilaterally and encompasses a wide array of potential differentials, including testicular torsion and epididymitis.

All cases should be approached thoroughly, as the risk of misdiagnosis (especially in cases of torsion or malignancy) are sizeable.

In this article, we discuss how to approach patients presenting with scrotal pain, then cover some of the potential diagnosis to consider.

Clinical Features

The vast majority of diagnosis for patients presenting with acute scrotal pain can be made through history and examination.

Key points to establish in the history include including the onset, course, and duration of pain, any associated urinary symptoms, relevant sexual history, and history of previous surgery.

Examination of the scrotum is covered in further detail here, however the main aspects to focus on are in the inspection, for testicular lie and any signs of inflammation, and palpation, to identify lumps or localised tenderness.

Cremasteric Reflex and Prehn’s Sign

The cremasteric reflex is elicited by stroking the proximal and medial aspect of thigh; a normal response is contraction of the cremaster muscle causing retraction of testes upwards on the ipsilateral side. Absence of the cremasteric reflex is a potential sign for testicular torsion, with a sensitivity of 88% and specificity of 86%.

Prehn’s sign is the alleviation of scrotal pain by lifting of the testicle and is suggestive of the diagnosis of acute epididymitis. It has a sensitivity of 91% and specificity of 78%.

Investigations

All patients presenting with acute scrotal pain should have a urine dipstick (/urinalysis) performed, with the urine sent for further culture (MCS, microscopy culture sensitivity) if required, as may suggest an infective element. A urethral swab can be taken if sexually transmitted infection is suspected.

Blood tests are often required, mainly FBC, CRP, and U&Es, especially as may support a diagnosis of infection or aid in the investigation on non-urological causes (see below).

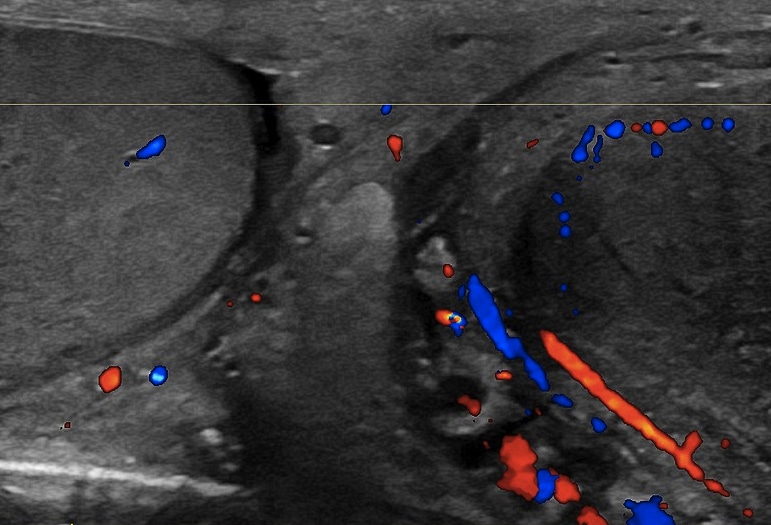

In cases of clinical equipoise, an ultrasound of the scrotum (Fig. 2) can identify any structural or inflammatory pathology and the patency of the blood vessels (however do not delay scrotal exploration if torsion is suspected)

Differential Diagnosis

Testicular Torsion

Testicular torsion is twisting of the spermatic cord with occlusion of the testicular and cremasteric arteries. This leads to ischaemia and subsequent testicular infarction. More details are described here.

It is most common in pubescent boys and young adults. The pain is sudden onset, very severe, and often associated with nausea and vomiting. On examination, there is unilateral scrotal tenderness, with a high testicular position and an abnormal lie; the cremasteric reflex will be absent.

If a case is suspected, urgent surgical exploration is required. On surgical exploration, if torsion is present, spermatic cord is untwisted and return of vascularity is observed, then a bilateral orchidopexy is performed. Orchidectomy is indicated if the testicle is infarcted and the contralateral testis is fixed.

Figure 3 – Scrotal Doppler ultrasound showing no blood flow in a case of testicular torsion

Torsion of Testicular and Epididymal Appendages

The testicular appendix, also known as hydatid of Morgagni, and epidydimal appendix are remnants of embryological development. They can also twist to result in a torsion, presenting with unilateral scrotal pain and tenderness, however often with normal testicular lie and present cremasteric reflex.

On examination, a “blue dot sign” might be present; the blue dot sign is found in the upper half of the hemi-scrotum sign and they occur due to infarction of the appendices. The mainstay of treatment is analgesia, however if any clinical uncertainty, surgical exploration is required to rule out testicular torsion.

Epididymitis

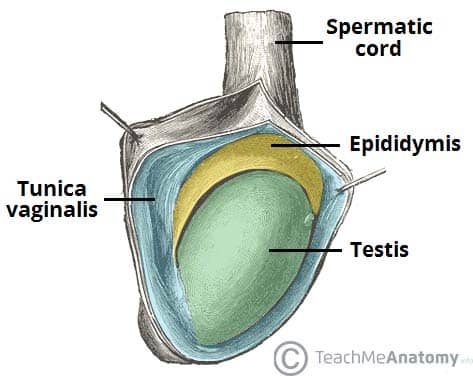

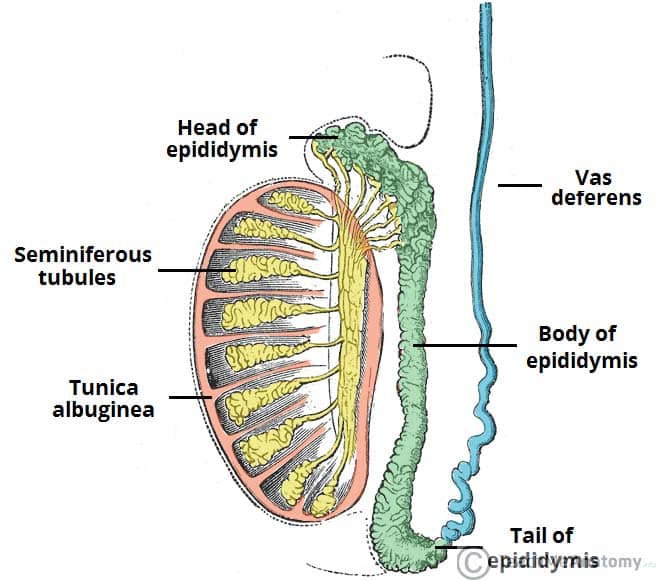

Epididymitis is inflammation to the epididymis (Fig. 4). As an approximation, in males aged <35 years old, the most likely mechanism is sexual transmission, whilst in males aged >35 years old, an enteric organism from a urinary tract infection is the more likely mechanism of the disease. Further details can be found here.

Patients will complain of worsening pain in the scrotum, and can have with associated symptoms of fevers, dysuria, haematuria, or urethral discharge. Pain can spread to the groin, as any lymphangitis tracks up the spermatic cord. On examination, the affected epididymis is swollen and tender, with overlying scrotal skin showing inflammatory changes. Commonly, the cremasteric reflex is present and Prehn’s sign is positive.

Definitive treatment is with antibiotic therapy, with antibiotic choice dependent on the suspected underlying organism (sexual transmission versus urinary tract infection).

Figure 4 – Diagram showing the anatomical positioning of the epididymus relative to the testis

Testicular Cancer

Whilst testicular cancer is often painless, in 5% of cases it can present with acute scrotal pain due to internal haemorrhage within the malignancy. It presents in young men and the pain is often associated with a palpable mass.

Raised tumour markers (beta-HCG or AFP) could be indicative of testicular tumours, however ultrasound of the testes will be diagnostic. Further imaging maybe indicated for staging. Further details are found here.

Definitive treatment is surgical (radical inguinal orchidectomy) and may require further adjuvant chemotherapy.

Referred Pain

Scrotal pain can also be the result of referred pain. As such, non-scrotal causes of scrotal pain should also be considered, especially in patients with normal examination findings.

The anteriolateral aspect of the scrotum is supplied by branches of the genitofemoral and the ilioinguinal nerve, whilst the posterior scrotum is supplied by the perineal branches of the pudendal nerve and posterior femoral cutaneous nerve.

Irritation of these nerves supplying the scrotum can result in referred pain. Such examples of this include luminal ureteric stones or strangulated inguinal hernia.

Non-Urological Causes

Henoch-Schoenlein Purpura

Henoch-Schoenlein Purpura (HSP) is an IgA-mediated small vessel vasculitis, which most commonly affects the skin, mucous membranes, and kidneys.

Whilst it commonly presents in children with the classic triad of symptoms (purpuric rash on limbs, arthritis, and abdominal pain), in some cases may present with scrotal symptoms, including pain, erythema, and swelling.

Initial blood tests may show raised CRP or ESR, however a raised serum IgA is more specific towards the diagnosis of HSP. Diagnosis is then made through biopsy (namely kidney or skin) to identify IgA deposition.

Viral Orchitis

Inflammation of the testes can occur due to a viral infection, most commonly mumps. Contrary to surgical causes of scrotal pain, viral orchitis can present with bilateral acute scrotal pain.

Post-puberty, 1 in 4 patients with mumps will have orchitis, and scrotal swelling and pain develop around 4 to 8 days after the initial parotitis. Management is conservative with analgesia; symptoms are self-limiting but scrotal swelling may persist up to 6 weeks post-infection.

Key Points

- Acute scrotal pain commonly presents on unilaterally

- Differentials are broad, including non-urological causes

- Most patients should have a urine dipstick and routine blood tests as a minimum for investigation

Many thanks to Mr Nasr Arsanious, Clinical Urologist at Croydon University Hospital, for his review and contribution to this piece