Introduction

- Introduce yourself to the patient and gain consent

- Wash your hands

- Explain the examination to the patient

- Reassure them that you will stop if it becomes too painful at any point

- Ensure verbal consent is adequately obtained

- Offer the patient a chaperone if required

Always work through a structured approach as below unless instructed otherwise; be prepared to be instructed to move on quickly to certain sections by any examiner.

Ensure to clearly verbalise your findings to the examiner as you progress through the examination.

Inspection and Palpation

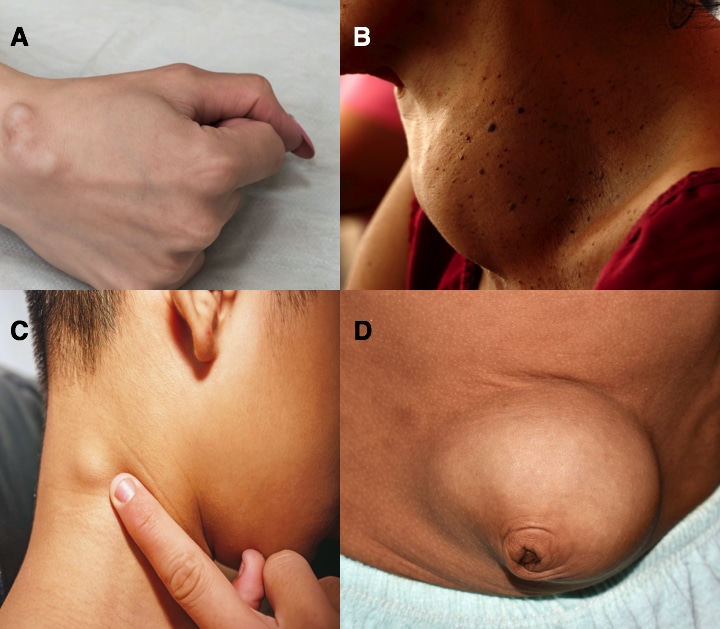

When examining a lump, both inspection and palpation are equally important (do not rush the inspection part, just to start palpating the lump)

A useful aide-memoire to ensure all potential aspects of a lump are covered is “3 Students and 3 Teachers go for a CAMPFIRE”:

- Site – Assess where the lump is located and its relationship to surrounding key anatomical structures (e.g. 3cm superior to the left medial epicondyle)

- Size – Estimate the size of the lump in at least two-dimensions (e.g. 4x6cm mass); if particularly large, consider using a ruler for greater accuracy

- Shape – Use geometric terms to describe the dimensions of the lump (e.g. round, irregular, lobulated)

- Tenderness – Is the lump painful on palpation? Ask the patient directly if there is any tenderness when gentle pressing the lump

- Temperature – Is the lump warm to touch?

- Transillumination – Apply a light source to the lump using a pen torch; fluid-filled lumps will allow light to pass through (e.g. hydrocoele)

- Consistency – Describe how the lump feels, such as soft (e.g. lipoma), firm (e.g. lymph node), or fluctuant (e.g. hydrocoele)

- Attachment – Is the lump fixed to other structures or can it be moved freely from underlying tissues?

- Mobility – Is the lump freely mobile or fixed in place?

- Pulsation – Check if the lump is pulsating, as this suggests a vascular aetiology (e.g. peripheral aneurysm)

- Fluctuation – Hold the lump on opposite sides and apply downwards pressure with one finger, and if fluctuant then this suggests a fluid-filled component

- Irreducibility – Can the lump be reduced? Apply gentle pressure to the lump, and if it disappears then it is reducible (e.g. inguinal hernia)

- Regional lymph nodes – Assess the lymph nodes which drain the site of the lump; any regional lymph nodes common suggest either an infective or malignant pathology

- Edges – Assess how well-demarcated the lump is, whether the borders are regular or irregular?

Auscultation

Remember to auscultate any lump, to assess for any bruits (suggesting increased or turbulent blood flow, e.g. a goitre or an aneurysm) and bowel sounds (suggesting bowel contents within a hernia)

Completing the Examination

Remember, if you have forgotten something important, you can go back and complete this.

To finish the examination, stand back from the patient and state to the examiner that to complete your examination, you would like to perform a full systems examination (depending on the suspected aetiology) and arrange appropriate imaging +/- biopsy of the lump