Introduction

Skin wounds are common and have a wide range of aetiologies, such as infection, trauma, or surgical incisions. Reassuringly, most wounds (particularly surgical) will heal without the need for any specialist input or intervention. Mostly this is achieved through appropriate dressings, with or without simple surgical wound closure.

The general principals to support any wound to heal are the same; wounds should be kept clean, protected, and in an environment to facilitate healing.

For simple lacerations or surgical wounds that have been primarily closed, they can simply be cleaned and dressed; in such cases, the skin can be considered ‘sealed’ after 48 hours, at which point further dressings are not necessarily required.

The same general principals apply to more complex wounds. However, more complicated interventions may be needed to facilitating wound healing in these cases.

Wound Management

When addressing any wound, the key principles required are:

- A comprehensive assessment of the patient to identify factors that are detrimental to wound healing should be performed

- If identified, causative factors of delayed wound healing should be controlled or eliminated; remember, dressings do not heal wounds, the patient does

- Perform a systematic assessment of the wound, a useful mnemonic is TIMES:

- Tissue involved (, such as viable or non-viable), Infection or inflammation, Moisture levels, Edge of the wound, and Surrounding skin

- Establish the wound management aims, based on the patient and wound assessment; ongoing reassessment and re-evaluation as the wound heals is essential

There are various types of wounds; a non-exhaustive list includes simple uncomplicated wounds, large or complex wounds, infected wounds, necrotic wounds (with or without infection), sloughy wounds, granulating wounds, or epithelializing wounds.

Wound Dressings and Adjuncts

There are many different dressings and wound management adjuncts available and many of these are available under different brand names. The key issue is to consider different dressing brands in line with the indication of dressing they fit in and consider what their advantage and disadvantages are.

All wounds should be treated individually while considering the experience you have with a product and no product fits all. When selecting a dressing, think about the TIMES assessment (as above), what you want to achieve, and therefore what dressing will help achieve that. You then need to select a plan in line with your patient assessment.

Negative-Pressure Wound Therapy

Negative-Pressure Wound Therapy (NPWT) or Topical Negative Pressure (TNP), commonly known by the trade name VAC (Vacuum Assisted Dressing), can aid the healing of wounds or temporise them pending formal reconstruction.

The negative pressure acts to encourage the blood supply to the wound site, reduce wound oedema, and remove the need for multiple dressing changes. NPWT is useful for larger wounds, by encouraging cell activity and wound perfusion, and stimulating granulation tissue formation.

A sealed dressing must be applied over the wound, then the device can be set to a negative pressure (usually between 75–150mmHg), which acts to removes the exudate through its pump into a collecting canister. Contra-indications for NPTW include active exposure over vessel or bowel, ongoing infection, or significant tissue necrosis requiring further debridement.

Surgical Management of Wounds

Most wounds can be managed with secondary intention healing or primary closure. However, when wounds are large or complex, more complex solutions may be required. Even in these cases, they may initially require management with dressings prior to definitive reconstruction.

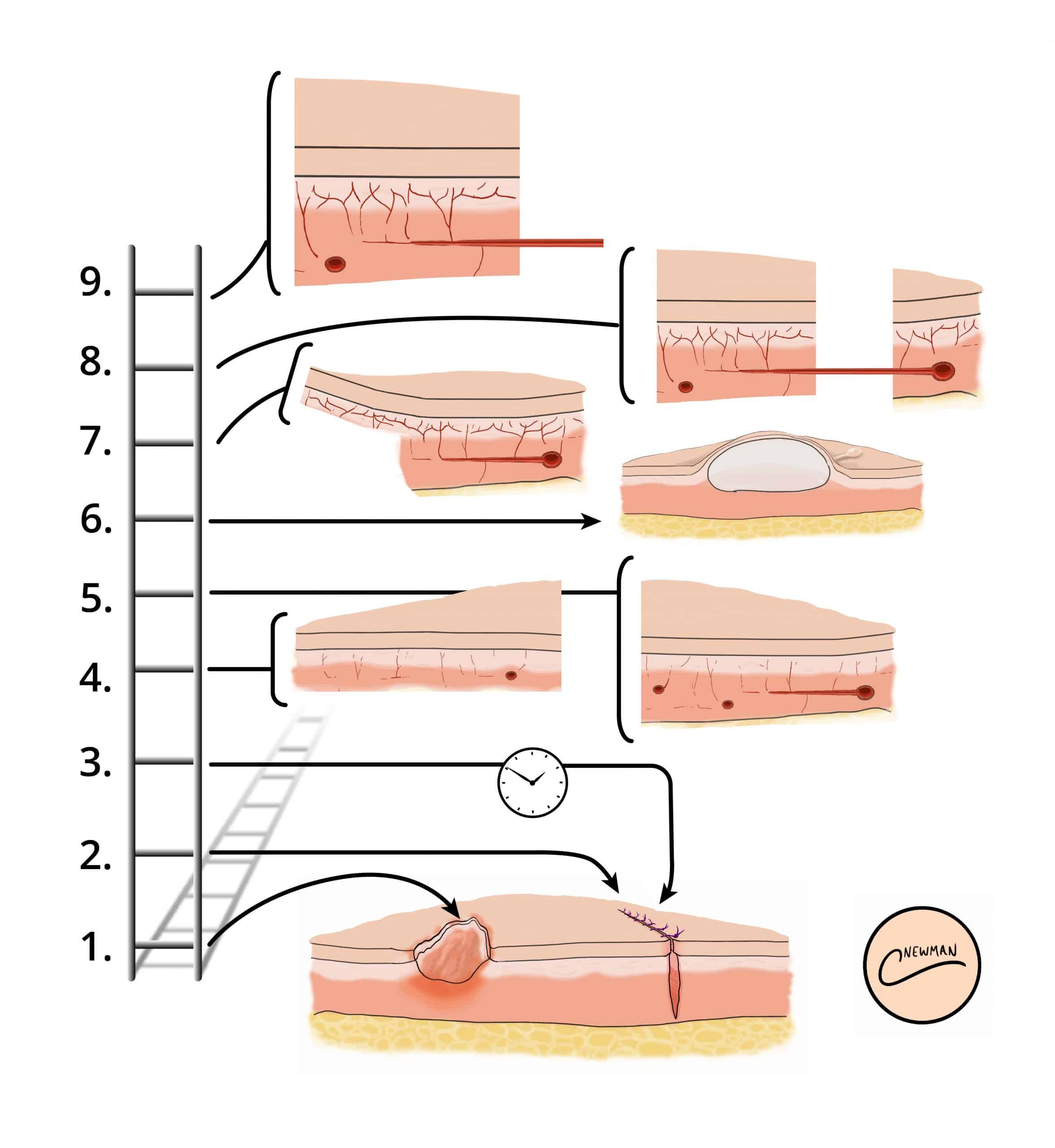

In cases requiring surgical closure +/- reconstruction, the “Reconstructive Ladder”* can be used (Fig. 2) as a step-wise progression of wound management options:

- Secondary intention

- Primary closure

- Delayed primary closure

- Split thickness graft

- Full thickness skin graft

- Tissue expansion

- Random flap

- Pedicled flap

- Free flap

*The reconstructive ladder is a guide and it can be appropriate to jump rungs on the ladder; other models have been proposed to reflect this, such as the “reconstructive tool box” or “reconstructive elevator”

Skin Grafting

Skin grafting can be defined as a surgical operation in which a piece of skin is transplanted to a new site on a patient’s body. More detail on skin grafts can be found here.

Skin grafts are necessary when the wound cannot be closed primarily and delayed healing is not appropriate. A skin graft has no blood supply, and therefore depends on the vascularised bed where it is placed.

There are two types of skin graft:

- Split-skin thickness skin graft (SSG) – does not contain the whole dermis

- Full-thickness skin graft (FTSG) – contains the whole dermis (also transplanting hair follicles)

Figure 3 – Granulation tissue developing on a skin graft wound

Split-Skin Thickness Grafts

Split-skin thickness grafts are harvested to contain a variable amount of dermis, leaving dermal remnants to allow re-epithelization of the donor site.

Split-skin grafting is often used for larger areas that require cover (for example in burns surgery) and they can be meshed to increase their size. SSGs are harvested with a dermatome or using a specialist blade (such as a Humby knife).

Full-Thickness Skin Graft

Full-thickness grafts contain the entire dermis and therefore the donor site must be closed directly. Only relatively small areas can therefore be taken and from regions with surplus skin (such as the supraclavicular fossa, pre-auricular or post auricular regions, the groin, or medial upper arm).

Full thickness grafts tend to be used for smaller areas, such as the face, where they will provide a better cosmetic appearance.

Skin Flaps

Figure 3 – A healing skin flap, used to cover an excision site

Unlike grafts, flaps bring their own blood supply. There are many ways to describe and characterise flaps; they can be described based on their circulation / blood supply, composition, or location / movement (local, regional or free). More detail on skin flaps can be found here.

Generally, a “flap” describes a process of taking a composite block of tissue, along with its blood supply, and moving it from one place to another (in this case, to cover a wound).

A flap can be thought of as being either “local“, where an area of tissues is taken from an area adjacent to the defect, or “regional“, where tissue is raised from nearby area and moved into the defect.

“Free” flaps describe a technique where tissue is raised with its blood supply, which is then completely detached and re-attached (anastomosed) to a new vessel at the donor site.

Key Points

- The general principals to support any wound to heal are the same; wounds should be kept clean, protected, and in an environment to facilitate healing

- Negative-Pressure Wound Therapy (NPWT), can aid the healing of wounds, acting to encourage the blood supply to the wound site and reduce wound oedema

- The “Reconstructive Ladder” can be used as a step-wise progression of wound management options

- A skin graft obtains a blood supply from its new site, whilst a flap brings its own blood supply